Abstract

Most countries in Southeast Asia are now positioning technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in the mainstream of education system thus becoming a priority in their education agenda to support the socio-economic development of the nation (SEAMEO VOCTECH 2012). TVET teachers and instructors are still the pressing issue due to a lack of quality and quantity in most countries. Most TVET teachers are recruited from fresh graduates of vocational and technical colleges and universities, thus lacking industrial experiences. This paper focuses on issues around the preparation of TVET teachers based on a meta-analysis of nine country reports presented during SEAMEO VOCTECH’s Expert meeting in collaboration with UNESCO UNEVOC in Thailand in December 2012 and updated from the country reports of training participants during fiscal year 2013/2014, and SEAMEO VOCTECH’s sharing sessions with the 2014 Governing Board Meeting. Based on these reports, this paper analyses common policies and practices, challenges, strategies and proposes some recommendations. The salient findings from Brunei on the current policies and practices include the effort for ensuring high quality teachers, enhancing teachers’ professional standards and enhancing the image of teaching as a first choice profession. Indonesia is focusing on teacher certification programs by stressing the importance of qualification and teacher competency standards. Lao and Cambodia are focusing on raising their teachers’ qualification to higher diploma and baccalaureate. Malaysia is addressing the complexity of various providers and perspectives by forming the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) and transforming teachers’ competencies by including industrial experience and considering industry needs, creating policy guidelines to develop highly effective instructors, and promoting teacher capacity building program by introducing a training levy. Myanmar is introducing e-learning systems to teachers to further their education and training in accordance with National Qualification Standards (NQF) and proposed ASEAN Qualification Standards (AQF). Singapore Institute of Technical Education is training its own teachers using competency-based curriculum (CBC) and authentic learning approach using TPCK model (Technological, Pedagogical, Content, Working Knowledge). Thailand is emphasizing the importance of education for sustainable development for TVET teachers, introducing Problem-based Learning (PBL) and using instructional media. Vietnam is highlighting the importance of upgrading teaching staff both pre and in-service focusing on management, contents, curricula, teaching and assessment methods. This paper also discusses some challenges and issues in TVET teacher education: inter alia the lack of industrial experience, attracting certain gender in teaching force, linking with industry, and issues of standardization. Selected strategies are also discussed, including recommendations to enhance the quality and quantity of teachers by addressing issues of flexibility and mobility.

1 Introduction

Referring to 2014 EFA Global Monitoring Report, there was a call for more effort to be made to ensure that children actually learn when they go to school, which can be achieved when governments invest in well-qualified and motivated teachers (UNESCO 2014). In academic or general education as well as in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), teachers are the backbone of education and training systems.

In Southeast Asian region, TVET teachers have been crucial issue in most member countries of ASEAN, both due to the lack of numbers and the quality of teachers (SEAMEO VOCTECH 2012). The increasing number of student enrolments requires more vocational schools and more teachers. Indonesia and Thailand are very progressive in promoting TVET at secondary level by targeting a TVET enrolment that equals or exceeds those enrolled in general education. In terms of quality, most new TVET teachers in the region are fresh graduates from vocational and technical colleges and universities, thus they lack industrial and teaching experiences (SEAMEO VOCTECH 2012). The lack of industrial working culture among TVET hindered the efforts of transferring the working culture to the students. These are some issues identified during the TVET Experts Meeting 2012 that require further studies.

Considering the crucial roles of teachers and many issues related to TVET teachers in the region, it was worth the effort to organize a TVET Experts meeting in March 2012 to share the current status and at the same time identify research agenda for TVET teacher education in the region, which was one of the bases of this paper. The experts meeting had the following objectives: (1) to map out the current development of TVET teacher education in Southeast Asian Countries, (2) to plan research agenda on TVET teacher education in the region, and (3) to offer a research capacity building opportunity for the experts group by participating in International Conference on “The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation”.

During the SEAMEO VOCTECH’s Governing Board Meeting in September 2014, the Centre also organized a sharing session on “Current TVET Policies, Issues and Strategies in SEAMEO Member Countries” participated by the High Officials in-charge of TVET in the SEAMEO member countries and invited speakers from ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nation) Secretariat, ASEAN-China Centre, and RAVTE (Regional Association of Vocational Teacher Education), the importance of addressing student and labour mobility in the region in anticipation of ASEAN Economic Community 2015 was highlighted. Having an ASEAN Qualification Reference Framework for easy referencing of qualifications among the countries within the region and TVET Quality Assurance Framework was considered necessary for the success of ASEAN Integration, especially on student and labour mobility. As part of assuring the quality of TVET, teacher competence was one of the important pillars to address in the meeting, especially on pre-service and in-service TVET teacher education, including continuous professional development (CPD).

To provide a summary of TVET teacher education and training in the 9 Southeast Asian countries namely Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, including the current status and future initiatives, the author presents a brief overview followed by a table listing salient and current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations proposed by the experts who participated in the meeting. The information was gathered primarily from the 2012 TVET Experts Meeting in Bangkok, SEAMEO VOCTECH’s Sharing Session 2014, and country reports from the Centre’s Regional Training Programmes 2013/2014. In addition, relevant data and information from UNESCO and UNESCO UNEVOC were also used as complements and enriching discussions.

2 Overview of TVET teacher education in selected countries in Southeast Asia

2.1 TVET teacher education in Brunei Darussalam

The Brunei government has taken initiatives in recent years to improve the quality of the teaching staff by upgrading the only teacher education institution in the country, which is the School of Hasanal Bolkiah Institute of Education under Universiti Brunei Darussalam (UBD), to be a graduate school. This means that all the teachers will be trained at only graduate level, such as Master of Teaching (MTeach), Master of Education, Doctor of Philosophy, and Graduate Diploma in Education. The key features of the MTeach are: (1) Extensive practical experience in the learning environment from the beginning of study, (2) Focus on research-based teaching, (3) Mentoring by experienced teachers and professionals in partner schools, (4) Deep understanding of the learning process and the design of teaching, and (5) Integration of the disciplinary knowledge of graduate entry students with masters-level study of how to teach (Chin 2012).

MTeach is a master programme offered at Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) level 7 or Australian Qualification Framework (AQF) level 9. The Graduate Diploma in Education is a one-year full-time initial teacher preparation programme introduced in the year 2012 that qualifies graduates for employment as educators. The GradDipEd is a one year 40 modular credits programme offered in the area of early childhood education, primary education, secondary education, TVET, counselling in education and special educational needs.GradDipEd is a graduate programmes offered at graduate level but not at master standard. It is a programme at Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) level 6 or Australian Qualification Framework (AQF) level 8.

Existing teachers who have yet to obtain a teaching qualification may enrol in the Diploma in Technical Education. It is a one-year programme designed for those teachers who need a teaching qualification but their educational background failed to meet the entry requirement of the University, i.e. those with a Higher National Diploma. Currently, the Diploma in Technical Education programme is run under the Continuing Education Centre of UBD.

In summary, there are three different types of initial teacher preparation for TVET teachers in Brunei (see Figure 1). From the entrance requirement perspective, the master level, MTeach caters for those TVET teachers with a 2:2 or higher classification degree at relevant field of study. The GradDipEd caters for degree holders at relevant field of study, while the Diploma in Technical Education caters for those TVET teachers with Higher National Diploma qualification. Although the programme structure for all three initial teacher preparation programmes are different, one common observation is that the programmes do not offer professional or technical subject matter (Chin 2012).

Figure 1: Pre-service vocational teacher education in Brunei Darussalam

Figure 1: Pre-service vocational teacher education in Brunei Darussalam

Further Chin stated that one of the obvious challenges for the current TVET initial teacher education programmes is the need to expose the teachers to the industries. The current MTeach, GradDipEd and Diploma in Technical Education programmes fail to address this issue.Although there are some positive changes in the TVET initial teacher preparation programmes, very little emphasis has been placed on the professional development of existing TVET teachers (see Table 1). Professional development of existing teacher should be in line with the changes in initial teacher preparation programmes.

Table 1: Brunei Darussalam’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations.

Recently, Brunei Government has endorsed TVET transformation, including the initiative to recruit teachers coming from industry. One of the key changes in TVET transformation in Brunei is renaming the Department of Technical Education (DTE) to bethe Institute of Brunei Technical Education (IBTE). It will be a system which builds on the educational foundation under SPN-21 and is aligned with the skilled manpower demands of industry and repositioned as a post-secondary education institution. Vocational education and training under IBTE will be practice-based, hands-on and experiential. The teachers who can best meet the needs of students in this learning environment are those who not only have the appropriate professional qualifications but most importantly the relevant industrial experience with pedagogic training. A new enhanced scheme of teaching service will be introduced to attract, retain and develop the right types and number of staff in meeting the needs of an expanded TVET system (Chin 2014).

2.2 TVET teacher education in Cambodia

Teacher education in Cambodia has two types: Academic and TVET teacher education. Academic teachers education is conducted by National Institute of Education (NIE) which is under the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoEYS), and TVET teacher education is conducted by Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training (MoLVT) and the National Technical Training Institute (NTTI) is the only institution under the umbrella of MoLVT which has the main duty to train TVET Teachers for the whole country. The TVET teacher training at NTTI is a one year programme consisting of 37 credits, offering Junior and Senior levels programmes, focusing mainly on skills upgrading in terms of andragogy and soft skills (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Pre-service Vocational Teacher Education in NTTI Cambodia (Source: NTTI website and Khemarin 2012, UNESCO UNEVOC 2014)

Figure 2: Pre-service Vocational Teacher Education in NTTI Cambodia (Source: NTTI website and Khemarin 2012, UNESCO UNEVOC 2014)

Table 2: Cambodia’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations.

There is still a need to improve the undervalued image of a vocational education as people view TVET as a second-choice (see Table 2 for more complete list). This being the case, the system is having difficulty to attract female applicants. Further, for the system to meet the demands of the industries, there is a need for NTTI to align the curriculum and link with industry to meet the demand for skilled workers and technicians. Strengthening and upgrading of technical teachers based on new technology and current and future needs of labour market will ensure that the TVET teacher education is able to contribute to the socio-economic development of the country (Khemarin 2012).

2.3 TVET teacher education in Indonesia

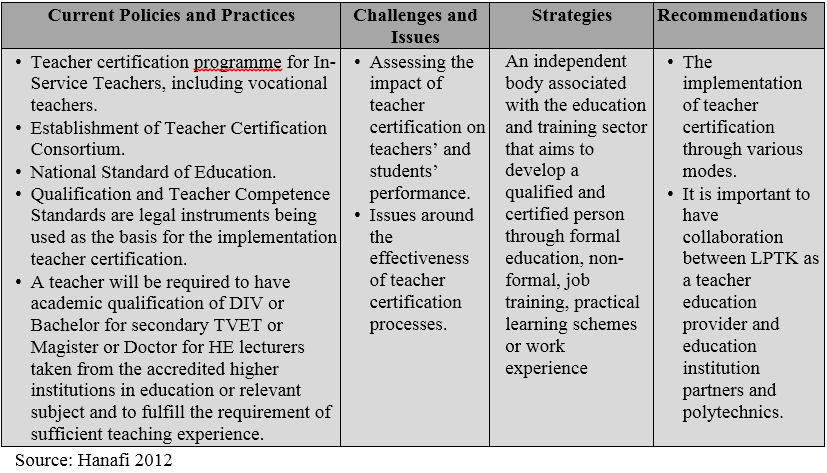

Skills gaps in Indonesia are considered as serious obstacles, thus investment in education and training is needed (UNESCO UNEVOC, 2014a). One of the policies in response to this issue was the formulation of Teacher Law of 2005 and its respective regulations for the organization of the teaching profession and its quality. The more comprehensive policies, issues, and strategies for TVET teacher education can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Indonesia’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations.

In Indonesia, TVET teachers for secondary vocational and technical schools are prepared by the Educational Institutions for Teaching Personnel (LPTK) comprising the universities that offer vocational and technical teacher education formerly known as Institute of Teacher Training and Education (IKIP) and Faculty of Teaching and Educational Sciences (FKIP) under universities, and private STKIPs (Colleges of Teaching and Educational Sciences). In addition, Vocational Education Development Centres, now called P4TK (Pusat Pengembangan dan Pemberdayaan Pendidik dan Tenaga Kependidikan/ Center for Development and Empowerment of Teachers and Education Personnel) are also in charge of providing in-service training for TVET teachers.

One of the current policies under TVET teacher education is teacher certification (Hanafi 2012). The initiative is intended to ensure that the teachers have mastered the required competencies that lead to the improvement of the quality of education in Indonesia. The programme is conducted as an in-service for teachers and is expected to produce better quality of education because the students, including vocational high school (SMK) students, are taught by certified and professional teachers. The teacher certification process is conducted through (1) the direct provision of the certificate, (2) portfolio assessment, (3) education and training of the teacher (PLPG), and (4) teacher professional education (PPG). The teachers are free to select the route they prefer considering their capability and capacity. Starting from the year 2011, the implementation of the in-service teacher certification is recommended to be education and training (PLPG) without neglecting the willingness of the teachers to take direct provision and portfolio assessment with certain requirements. In addition, collaborative Teacher Professional Education (PPG) program is being initiated for pre-service teachers of vocational high schools (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Pre-service and In-service Vocational Teacher Education in Indonesia (Source: Hanafi 2012 and Nurlaela 2014)

Figure 3: Pre-service and In-service Vocational Teacher Education in Indonesia (Source: Hanafi 2012 and Nurlaela 2014)

Based on this law, the minimum educational qualification for TVET teachers at secondary vocational schools (SMK) is either Diploma 4 or Undergraduate Degree. Under the recently initiated Teacher Profession Education Programme (PPG), the graduates from D4 or Bachelor (S-1) may pursue for one to two semesters of teacher education and training. For those graduated from non-pedagogic programmes (non-kependidikan) in the areas not offered by LPTK, they may pursue teaching profession through PPG with additional one to two semesters of teacher education and training. The model for PPG is represented by the process and product components of education. The process of education takes two semesters, one semester for strengthening pedagogic (including practice teaching workshop) and relevant technical/vocational competencies, and second semester for practice teaching. The students then take a competency assessment to qualify for receiving two certificates: teaching certificate and vocational/technical expertise certificate.

2.4 TVET teacher education in Lao PDR

Based on UNESCO UNEVOC (2013), many of TVET teachers in Lao PDR were lacking real work experience. Most teachers graduated from technical schools, polytechnics, colleges or universities. Non-formal TVET is under the Ministry of Education and Sports (MOES) and the programmes run in Integrated Vocational Education and Training (IVET) schools (a few centres), and in Community Learning Centres (CLCs) across the country. In addition, the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (MOLSW) runs 4 skills-development centres.

Vocational Education Development Center (VEDC) (now Institute for Vocational Education) and the National University of Lao PDR (NUOL) have been playing a critical role in pre-service TVET teacher training. The Faculty of Engineering of the NUOL train TVET teachers at Bachelor level, whereas, VEDC train TVET teachers and trainers at Higher Diploma and Bachelor (continuous) level (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Pre-service Vocational Teacher Education in Lao PDR (Source: Sisoulath 2012; UNESCO UNEVOC 2013)

Figure 4: Pre-service Vocational Teacher Education in Lao PDR (Source: Sisoulath 2012; UNESCO UNEVOC 2013)

In 2008, the government of Lao decided to expand the capacity for preparing teachers. This resulted to the MOES expanding TVET teachers training capacity to some selected TVET institutions, 9 in total but only 7 in operation. As planned, a total of 600 new teachers were to be trained each year during the next five years and the MOES, with ready and allocated appropriate resources based on a yearly plan and curricula submitted by schools approved by MOES (Sisoulath 2012).

In-service training or study programmes have been conducted for TVET directors, officers and teachers in a range of TVET areas, with duration ranging from one day to one year, either in Lao PDR or abroad. Currently, the VEDC and some major TVET schools conduct in-service training for TVET teachers, covering the areas of pedagogy and technical fields.

A number of major issues of TVET teachers need be addressed by the system, including lack of coordination among providers, low qualification of teachers, lack relevant pedagogical preparation, limited movement and low salary (see Table 4).

Table 4: Lao PDR’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations.

2.5 TVET teacher education in Malaysia

The main government agencies involved in TVET teachers training are Ministry of Education (MoE) and Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE), which were merged into one as MoE, Ministry of Human Resources (MoHR), Ministry of Youth and Sports (MYS) and Majlis Amanah Rakyat (MARA). The aspects of qualification and quality of the TVE training have become issues in teacher training in the country. It is expected that by the year 2020 all teachers must possess a first degree before they can join the teaching profession to ensure all teachers pass the ‘quality criteria’ before leaving the training institute (Hassan et al. 2012). Figure 5 shows common approaches to TVET teacher education in Malaysia.

Figure 5: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Malaysia (Source: Hassan 2012)

Figure 5: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Malaysia (Source: Hassan 2012)

As shared during the Experts Meeting in 2012, Hassan observed that current governance structure still lacks coordination, sharing of resources, and articulation within the overall system, thus reflecting inefficiency in the system. There is also no single oversight body to provide overview of TVET landscape. Four policies have been introduced to enhance access to quality TVET in Malaysia: (a) improving the perception of TVET and attracting more trainees; (b) upgrading and harmonising TVET curriculum quality in line with industry requirements by initiatives which include standardising TVET curriculum, recognising the national skills qualification, and establishing a new Malaysian Board of technologists; (c) developing highly effective instructors, including the establishment of a new Centre for Instructor and Advanced Skills Training; and (d) streamlining the delivery of TVET, including a review of the current funding approach of TVET and to undertake performance ratings of TVET institutions (Hasan 2012).

There is a need for Malaysia to have new National TVET-Teacher Qualification Standards and training policies in conjunction with the transformation of the vocational education system. Hassan also highlighted the need to strengthen the skills accreditation programmes in order for the new models of TVET teachers to fulfil high standards of teacher’s quality and market needs (see Table 5 for more information about current policies, issues, strategies, and recommendations).

Table 5: Malaysia’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations.

2.6 TVET teacher education in Myanmar

TVET as subjects are first introduced in vocational schools, technical high schools or agricultural high schools. At post-secondary level, a wide range of TVET courses are offered under the Ministry of Industry. There are also non-formal TVET programs under the coordination of the Myanmar Educational Research Bureau (MERB). The non-formal TVET courses provide selected types of learning to sub-groups in the population such as handicapped persons, rural populations, school drop-outs and out-of-school youth, and unemployed or underprivileged youth. These programmes are offered by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and international organisations (UNESCO UNEVOC 2014b).

At present, there are thirty-two Technological Universities, three Government Technological Colleges, eleven Government Technical Institutes and thirty-six Government Technical High School in Myanmar offering TVET to students to study and continue to the higher education in many skilled-based programmes, which are highly relevant for national development (Tun 2012).

In Myanmar, the Ministry of Science and Technology through the Department of Technical and Vocational Education (DTVE) is responsible for planning and management of Technical and Vocational Education. DTVE also in charge of preparing highly qualified and proficient teachers and administers vocational schools, technical high schools and agricultural high schools (UNESCO UNEVOC 2014b).

The country has two TVET teacher training centres under the Ministry of Science and Technology that train and produce competent technical teachers to become knowledgeable and skilful in their respective technical and engineering fields. In addition, there are three TVET Teacher Training Centres under the Ministry of Labour and six TVET Teacher Training Centres under the Ministry of Industry (UNESCO UNEVOC 2014b). (See Figure 6 for more illustration on TVET teacher education in Myanmar). Between 1988 and 2010, teachers were recruited from students who passed the matriculation examination and contracted for serving as teachers in technical institutes.

Figure 6: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Myanmar. (Source: Tun 2012, UNESCO UNEVOC 2014b)

Figure 6: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Myanmar. (Source: Tun 2012, UNESCO UNEVOC 2014b)

At present TVET policy is focused more on TVT reform, especially on Technical and Vocational Education for Youth Employment and the establishment of a training concept. A few issues and challenges that the country still faces in regards to TVET are, inter alia, (a) mismatch between demand and supply, (b) lack of adequate industry participation, (c) insufficient number of trainers, (d) inadequate vocational training infrastructure, (e) low employment outcome of graduates, and (f) lack of a tripartite (government, employer and worker) collaboration. (UNESCO-UNEVOC 2014b). Tun (2012) highlighted TVET policies, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations that can be seen in Table 6.

Table 6: Myanmar’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations (Tun 2012)

2.7 TVET teacher education in Singapore

Under the Ministry of Education Singapore, the Institute of Technical Education (ITE) and polytechnics are the major suppliers of skilled labour force in Singapore. The Ministry of Manpower, i.e. the Singapore Workforce Development Agency offers continuing education and training which is industry-based and is accessible to working adults. For this paper, the author only focused on the TVET teacher education in ITE.

ITE is a principal provider of career and technical education at the technician and associate professional level and a key developer of national occupational skills certification and standards in the country. ITE adopts practice-based, hands-on experiential learning, which is different from that of mainstream schools and other tertiary institutions in Singapore. This strategy suits its students who learn well by doing. ITE uses the “teachers have to know and be able to do” philosophy in training the teachers for the institute’s needs (Ng 2012).

To cater to this unique pedagogic need of its teaching staff, ITE has since 1981 provided its own teacher education which emphasizes competence-based, practice-oriented teaching complemented by on-the-job mentoring and supervision by experienced teachers, an approach adapted from Germany. See Figure 7 for current model of TVET teacher education in ITE Singapore.

Figure 7: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in ITE Singapore (Source: Ng 2012)

Figure 7: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in ITE Singapore (Source: Ng 2012)

Key issues and challenges relating to the implementation and outcomes include the use of the CBC model of learning – applicable in authentic learning environments, the introduction of 3-level vocational pedagogy framework (TPCK) and, the capability to systematically and progressively develop its TVET teachers towards teaching excellence via professional pedagogic development and communities of practice. The summary of TVET teacher policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations identified by Ng (2012) can be seen in Table 7.

Figure 8: Vocational Pedagogy in ITE Singapore (Source: Ng 2012)

Figure 8: Vocational Pedagogy in ITE Singapore (Source: Ng 2012)

Table 7: ITE current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations (Ng 2012)

2.8 TVET teacher education in Thailand

Thailand also experienced a lack of quantity and quality of technical and vocational teachers. The Office of Vocational Education Commission (OVEC) Thailand launched various programmes for improving vocational teachers, such as inviting foreign experts to be facilitators for foreign languages and occupational courses, improving learning management using project- or problem-based learning (PsBL), improving teachers’ occupational skills, working on research for developing instructional media “The Innovative Logistics Professional’s Training for Border Trade with the Greater MEKONG Sub-region”, strengthening TVET networking with other organizations in both public and private sectors, and expanding overseas partnerships (Sriboonma 2012).

According to Songthanapitak (2013), a Delphi study on policy reform found that it was necessary (1) to standardize production and development systems of vocational teachers and workplace trainers, in terms of qualification frameworks at national and regional levels and (2) to establish a system of laws and regulations to enforce efficiencies of vocational teacher education (VTE) production and development.

The aims of these policies are(1) to reform Vocational Teacher Education in Thailand according to demands of users and deal successfully with economic, social and political changes, (2) to develop vocational teacher students, vocational teachers, workplace trainers and university lecturers to be competent and provide work experiences tuned to the demands of users, (3) to increase efficiency of educational administration by organizational structure, decentralization, national and international standardization, mobilization of resources and effective models of management.

Organisational structural reform, includes (1) the production and development of vocational teachers can be operated under one organization with international collaboration, thus the country can produce competent vocational teachers and workplace trainers without expanding the number of institutions and campuses and, (2) the idea that the private or industrial sectors should be the main bodies responsible for the production of vocational teachers and workplace trainers.

Under curriculum reform, it includes policies (1) to develop selection processes for qualified vocational teacher students which recruit competent candidates, (2) to increase incentives to attract candidates, (3) to standardize vocational teacher education system in all fields according to National Qualification Framework for Vocational Education, (4) to develop VTE programs as competency-based and modular curricula with Accreditation of Prior Learning (APL) and credit bank. Balance of theories, field practices and practical work must be considered.

Under learning reform, the aims are to (1) accelerate the development of essential life skills, (2) to integrate learning management to develop skills and attain excellence in a particular field for each teacher student. Alongside these schemes there are also strategies to enhance required competencies of vocational teacher students such, as awareness of safety, entrepreneurship, green jobs and green technologies and, to collaborate practical learning with the workplace to carry out dual education or cooperative education.

Under management reform, it was proposed (1) to organize a national committee or an organization, (2) to establish networks for Vocational Teacher Education that connect to Cluster of Vocational Education, (3) to improve laws and incentive system in order to motivate entrepreneurs to cooperate with VTE institutions, and (4) that VTE institutions identify areas of excellence and their own expertise as well as design new management models with a specified Key Performance Indicator (KPI) to be used for continuous assessment and development.

For continuous professional development for teacher trainers or faculty staff, they should be encouraged to refresh knowledge and skills in industries with high standard and up-to-date technologies. Tax reduction can be used as a scheme to attract the private sector as well as awarding grants to lecturers in research on learning management as well as innovations.

To develop vocational teachers, the government should issue laws permitting vocational teachers to be trained at industries according to the needs of teachers and institutions and to recruit industries with modern technologies as networks for developing competencies of vocational teachers and workplace trainers by providing tax levy. In order to develop a proper teaching profession, the government should (1) set up Professional Standards of vocational teachers in terms of educational science, knowledge application, particular legal professional organization for issuing of teaching licenses, (2) establish frameworks of competency-based standards for vocational teachers and workplace trainers at ASEAN regional and international level, and (3) VTE institutions must be assessed, certified and registered, and (4) issue regulations concerning remuneration system and career path of vocational teachers, similar to those in industry.

Based on the expert meeting in 2012, the country expert from Thailand shared the following TVET teacher policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations; see in Table 8.

TVET teaching in Thailand is offered at universities, teacher training colleges and specialized colleges in the areas of physical education, vocational education, technical education, and agricultural education. These institutions prepare TVET teachers by providing both technical/vocational (occupational) and pedagogical courses concurrently or spread out during the programme. For an illustration, see Figure 9.

Table 8: Thailand’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations

2.9 TVET teacher education in Vietnam

The Vietnamese government has committed to make changes in the education and training system to develop the skills, attitudes and intellectual capacity needed to build an adaptable and competitive workforce (Hai 2012). Hai further explained that the Education Development Strategic Plan focuses on education management and teacher development as two main factors for education development.

Improvement in teacher training is focused on standardizing and upgrading teacher qualifications and training institution capacity and on adapting training and teacher support to the new curricula and methodologies (Huang, 2005 as cited in Hai, 2012). In addition, there is a concerted effort to upgrade the capacity and qualifications of teachers, teacher trainers, and Teacher Training Institutes (TTIs) as well as in-service training to introduce the new student curricula and methodologies to teachers (Hai 2012).

Figure 9: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Thailand (Source: Sriboonma 2012; Songthanapitak 2013)

Figure 9: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Thailand (Source: Sriboonma 2012; Songthanapitak 2013)

Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) is mandated to provide a pre-service training curriculum framework that specifies contents and duration of required coursework. The framework includes the number of credit hours for general education, professional education and practice teaching. Pre-service training is provided by universities. However, there are no universities that provide a direct programme for TVET teachers. Those who intend to become TVET teachers must graduate from a university and take pedagogical courses (Hai 2012).

In-service training is offered through the teacher training institutions under MOET or under MOLISA (Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs). In-service training is often held on Saturdays and during the summer. Like pre-service training, it is regulated by MOET. MOLISA recruits professional/skilled industry engineers and employees with professional knowledge and experiences to be teachers and instructors. Education Training Units (ETUs) offer continuing education for TVET teachers in vocational pedagogy and occupational skills. See illustration in Figure 10.

The current challenges and issues that the Vietnamese vocational education teachers are facing include the followings: that education should be made a national and leading policy; that the quality of TVE teacher education is low compared to those in the region and that the TVE teachers’ salary is considered average locally but rather low compared to those in the region; there is no professional development plan for those taking up the pre- and in-service training schemes; the teaching equipment or aids are insufficient and out of date; there are too many industries to cater for while there are no specific training programmes for TVE teachers.

Figure 10: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Vietnam (Source: Hai 2012)

Figure 10: Vocational Teacher and Instructor Education and Training in Vietnam (Source: Hai 2012)

To address the issue, Hai (2012) suggested the following initiatives: the development of indicators and evidences for TVE standards, as well assessment tools that would help VTE teachers to do self-assessment against professional standards; the development of a quality assurance framework and, to conduct research on training needs and development of training materials. To provide a summary of the current TVET teacher education policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations based on the expert’s country report from Vietnam, see Table 9.

Table 9: Vietnam’s current TVET policies and practices, issues and challenges, strategies, and recommendations (Hai 2012)

3 Synthesis of TVET teacher education in selected Southeast Asian countries

There are many factors affecting TVET teacher education, among others are organisational change, technological development, reform and changing political priorities, internationalisation, labour market development, cultural changes, changing paradigm of learning, and new target groups (Lipsmeier 2013). Taking these factors into consideration, TVET teacher education in Southeast Asian region is also changing and each country under study is unique due to their different environments.

Regardless of the diversity of TVET teacher education in the SEAMEO member countries, there are two salient modes of preparing TVET teachers in the participating countries: through universities and through open recruitment of experienced members of the workforce or practitioners. Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam under MOET prepare their TVET teachers primarily through university or training institutes. In these countries most of the TVET teachers are recruited from fresh graduates and many of them are lacking of industrial exposure. Industrial training or exposure that offers a combination of hands-on practice and good pedagogical knowledge, technical know-how and real working environment is needed. This will provide trainee teachers with authentic, relevant and current learning experiences, which has been addressed in some countries. Singapore recruits its TVET teachers from the candidates who have strong technical and vocational skills background regardless of the minimal pedagogical skills they have. After being recruited, the successful candidates will go through pedagogical training and mentoring provided by the TVET institution, not by a university. This model has attracted policymakers from Brunei and this will likely be the preferred model for recruiting and preparing their teachers.

Lipsmeier (2013) explained that within the first mode (TVET teacher education through university education), it can be categorized again into two: concurrent and consecutive models. The concurrent model represents three areas of competences to be learnt by pre-service teachers in parallel: main subjects (vocational disciplines), vocational pedagogy, and vocational skills. This model is very similar to the practices in many SEAMEO member countries where TVET teacher education is offered at a university (normal universities in China and Philippines). The consecutive model represents bachelor’s degree in technical or vocational discipline followed by vocational pedagogy. This is similar to those teachers recruited from non-education universities (learning only engineering or vocational courses), but they have to take pedagogy lessons afterward.

As TVET programmes are industry-based and industry-competencies-orientated, it is necessary therefore, for TVET teachers to have the right set of competencies and right work environment when delivering technical and vocationally- oriented programmes so that the students are provided with the right set of skills and knowledge required by the industries.

Referring to ASEAN Community 2015, we expect that these sets of vocational and technical skills and knowledge that the TVE teachers are being given should also be relevant not just to the needs of a particular country, but if possible, applicable across the region. The setting up of a regional TVET standard and qualifications reference framework will help address the issue of TVET teacher competency and mobility across the region.

Further, the importance of cooperation between training institutions and industry cannot be over-emphasized; therefore, dialogue between them on activities such as curriculum development, revision and programme delivery should be held regularly to ensure programme relevance and currency to the industry needs.

4 Recommendations

To ensure that TVET teacher education programmes are relevant to the needs of the industries, there is a need to provide the TVET teachers with industrial experience according to the specific country requirements. Developing linkages with the industries during initial teacher preparation programme is needed, with specific emphasis on the unique nature of TVET and the realities of the world of work, and with less emphasis on the attaining higher academic degrees. A programme that is more relevant and applicable to knowledge and skills in terms of changing technology and working practices. Realising the importance of industrial experience, Lipsmeier (2013) stressed the importance of industrial experience for all TVET teachers by suggesting any of the following options: (a) 2-3 years full traineeship before becoming a teacher, (b) 6-9 months internship before becoming a teacher, (c) internship in industry while working as a teacher, (d) internship in production school, (e) internship in research institutions, or (f) internship in industry with sophisticated labour organisation.

Lipsmeier further emphasized that internship is not an industry visit but trainees should submit a report and document their learning process. He also noted that in Germany TVET courses are taught by teachers and instructors. Teachers teach academic subjects whereas instructors with industrial experiences teach practical competencies.

To keep abreast with the fast changing technology, there is also a need to modify and develop competency-based curriculum for teacher training to be more responsive to the current trends of TVET and various industry requirements. In addition to practical and hands-on industrial exposure of TVET teachers, there is also a requirement for constant and regular staff-capacity building, provision of training programmes in the development and upgrading of teaching aids and materials, taking into consideration the provision of adequate and up-to-date TVET equipment and facilities according to the training needs of workshops and laboratories. To cater for the needs of the 21st century skills required by the industries, and to keep abreast with technology, TVET teaching environment should be equipped with new technology and improved internet connectivity, as this will make them aware of the new trends in teaching and technology across the region and beyond.

To answer the issue on the demand and supply of quality TVET teachers, there is a need for the TVET across Southeast Asia to come up with a policy that focuses on access to quality TVET teacher education. The creation of database of TVET experts in each member of SEAMEO will be useful source to find quality TVET teachers.

In addition, the call to develop an internationally accepted TVET teacher education standard framework for the region, such as the introduction of ASEAN TVET Quality Assurance and Qualification Reference Framework will ease the issue of TVET teachers’ mobility across the region as all TVET teachers would have met the same standard and quality for TVET teaching.

Other areas highlighted that need consideration are the need for a platform for the TVET teachers to voice their concerns, e.g. through the Southeast Asia Vocational Education Research Network (SEAVERN), Regional Cooperation Platform (RCP) that recently helped the initiation of Regional Association of Vocational Teacher Education in Southeast and East Asia (RAVTE), and Regional Cooperation of TVET (RECOVET). The introduction of the concept of greening TVET using e-learning and radio-learning teaching programs, and the introduction of a community of practice as a sort of model for continuous professional development, are some of the initiatives that are worth sharing.

There is a need to enhance pedagogical education with more distinctive nature of TVET or called TVET pedagogy by considering authentic teaching-learning whereby real industry working environment can be replicated in a school setting or by providing more opportunities to collaborate and utilize the workplace as a learning venue. Using a competency-based model and incorporating project and problem-based learning are timely now as the demand from industry for technical skills and transferable or employability skills is becoming more obvious and stringent. The adoption of vocational pedagogy coupled by the use of technology and 21st century skills, such as in PTCK Model in ITE Singapore is worth considering. In the area student assessment, considering the complexity of individual students and fast changing technology and industry demand, considering holistic and authentic assessment is advisable and appropriate in this era. This can be done by utilizing various assessment tools such as rubrics, portfolio assessment, and performance-based assessment where learning outcome becomes the focus of the assessment.

With concerted effort, support and collaboration from the various governing bodies of the Southeast Asian member-countries, various industries, and international organisations, it is envisaged that the TVET teacher education in Southeast Asia will catapult to a much higher level, benefitting various stakeholders of the TVET system across the region and beyond.

References

Chin, W. K. (2012). TVET Teacher Education in Brunei Darussalam: Transformation and Challenges. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Chin, W. K. (2014). The Transformation of Vocational and Technical Education in Brunei Darussalam. A country paper presented during the 25th SEAMEO VOCTECH Governing Board Meeting, 23-25 September 2014, ITE Singapore.

Hai, N. H. (2012). The Technical and Vocational Teacher Development in Vietnam: Issues and Solutions. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Hanafi, I. (2012). Teacher Certification Program in Indonesia: An Effort in Realizing a Qualified Vocational Education. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Hassan, R., Razzaly, W., & Alias, M. (2012). Technical and Vocational Education Teachers in Malaysia. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Huang, S. S. (2005). Viet Nam: Learning to teach in knowledge society. Working paper No. 2005-03. World Bank, Washington, D.C. Online: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/main?menuPK=64187510&pagePK=64193027&piPK=64187937&theSitePK=523679&entityID=000090341_20061212161346 (retrieved 20.12.2008).

Khemarin, C. (2012). TVET Teacher Education in Cambodia. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Lipsmeier, A. (2013). Approaches towards enhanced Praxis-Orientation in Vocational Teacher Education. A paper presented during Regional Conference on Vocational Teacher Education. Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 24-25 October 2013.

Ng, S. (2012). TVET Teacher Education in Singapore Institute of Technical Education. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Nurlaela, L. (2004). Model PPG Guru Vokasi (Models of Vocational Teacher Professional Education). Paper presented during 3rd International Conference on TVET, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, 12-15 November 2014.

SEAMEO VOCTECH (2012). TVET Teacher Education. A report of the Experts Meeting Organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH in collaboration with UNESCO-UNEVOC. Bangkok 25-28 December 2012.

Sisoulath, S. (2012). TVET Teacher Education in Lao PDR. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Songthanapitak, N. (2013). Vocational teacher education reform in Thailand: Policy suggestions. Paper presented during the 24th SEAMEO VOCTECH Governing Board Meeting in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam.

Sriboonma, R. J. (2012). Vocational Teacher Education in Thailand: Current Status and Future Initiatives. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

Tun, W. M. (2012). TVET Teacher Education in Myanmar. A country paper presented during the Experts Meeting organised by SEAMEO VOCTECH and UNESCO-UNEVOC in Conjunction with International Conference on The Excellence in Teacher Education and Research Innovation by Rajabhat Universities Network, Bangkok, Thailand, 25-28 December 2012.

UNESCO (2014). Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. Education for All (EFA) Global Monitoring Report 2013/2014.

UNESCO UNEVOC (2014). World TVET Database: Cambodia. Online: http://www.unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=World+TVET+Database&ct=KHM#par0_4(retrieved 09.11.2014).

UNESCO UNEVOC (2014a). World TVET Database: Indonesia. Online: http://www.unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=World+TVET+Database&ct=IDN (retrieved 09.11.2014).

UNESCO UNEVOC (2014b). World TVET Database: Myanmar. Online: http://www.unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=World+TVET+Database&ct=MMR(retrieved 09.11.2014).

UNESCO UNEVOC (2013). Compilation of country papers report. Online:http://unesco/unevoc/user_upload/docs (retrieved 09.11.2014).

Citation

Paryono, P. (2015). Approaches to preparing TVET teachers and instructors in ASEAN member countries. In: TVET@Asia, issue 5, 1-27. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue5/paryono_tvet5.pdf (retrieved 23.7.2015).