Abstract

The didactical approaches teachers deploy in delivering construction technology subjects at the school level in Zimbabwe are broadly meant to prepare learners for an easy transition into the labour market, further training and self-employment after school. This paper explored the vocational didactics teachers use to effectively deliver construction technology-related subjects such as Building and Wood Technology and Design at the school level. A systematic review of curriculum documents such as the school TVET policies, syllabi, evaluation reports and research publications was done. The systematic review included documents on vocational didactics for TVET schools elsewhere and those in Zimbabwe from 1980, when the country achieved independence, to the present day. This was done to understand the philosophical shifts in post-independence vocational didactics intended to improve equity and inclusion in the first ten years and later to solve growing unemployment for school leavers after 1990. Findings suggested that, in the first phase after independence, teachers adopted those didactical skills that emphasised the acquisition of craft skills needed in the production line and nurtured learners’ positive attitudes towards manual work and trades. The second phase, after 1990, focused on inclusive vocational skills development to solve socio-economic challenges. A stronger orientation emerged towards equipping learners with high-level technical, entrepreneurship and problem-solving skills for self-employment. Vocational didactics in construction technology must continue to evolve with sustainable skill set requirements for green jobs and workplaces so that school leavers can easily advance with higher-level training and transit into the labour market with relevant skills.

Keywords: vocational didactics, didactics, technical vocational education and training, construction technology, vocational skills

1 Background and Introduction

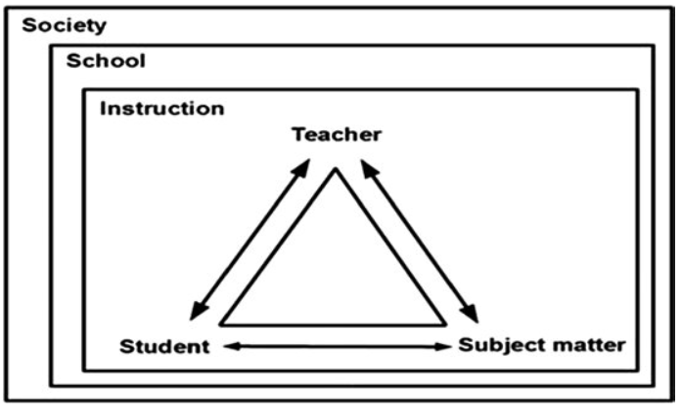

It is broadly acknowledged that the role of technical vocational education and training (TVET) is to prepare the workforce with sustainable technical skills for socio-economic roles and development (UNESCO 2017). Due to the global unemployment crisis, especially that of school leavers, the delivery of school TVET is increasingly putting more emphasis on equipping learners with relevant sustainable technical skills to fit the competency profiles of semi-skilled job entrants and on further training (Mbongwe 2018). TVET teachers are, therefore, required to use effective adaptive vocational didactical methodologies in order for students to enjoy and comprehend what they are learning. Vocational didactics refers to the art and science of teaching within vocational education, emphasizing the integration of vocational expertise and pedagogical techniques (Berglund & Lister 2010). Vocational didactics focuses on the learning activities involved in acquiring a trade, where an individual possessing knowledge (typically the teacher) engages with a learner (usually the student) to share knowledge and develop skills through structured instructional methods (Nore 2015; White et al. 2022). As explained by Berglund and Lister (2010), vocational didactics is best understood by means of a didactical triangle, shown in Figure 1. propounded by Hudson and Meyer (2011).

Figure 1: The didactical triangle adapted from Hudson and Meyer (2011, 8).

The didactical triangle represents the dynamic relationships between the teacher, student, and content (Lampiselkä et al. 2019). It emphasises that teaching and learning are interactive processes influenced by these three core components. The teacher plays a key role in guiding the learning process, facilitating understanding, and adapting content delivery to meet students’ needs. Meanwhile, the student actively engages with the material, constructing meaning and reflecting on their understanding. Students’ prior knowledge, motivation, and learning strategies shape how they interact with the teacher and the content. The content itself, which consists of the knowledge, skills, or subject matter being taught or learned, must be structured in a way that is accessible to the students, with its presentation mediated by the teacher (Berglund & Lister 2010). In line with the didactic triangle, vocational education teachers should, therefore, possess both the content and skills related to the trade they teach and didactical skills appropriate to TVET.

Several developed countries achieve low school-leaver unemployment rates by using appropriate vocational didactics on their students at the school level to equip them with the relevant technical skills for the labour market (Langford et al. 2015). However, Zimbabwe, a developing country, blames the rising school leaver unemployment on inappropriate vocational didactics which are not equipping learners with the sustainable skills to adapt to the changing skill sets for green jobs (Muzari et al. 2022). As a result, there have been several innovations and shifts in vocational didactics at the school level in Zimbabwe for construction technology-related subjects. The innovations include transiting from predominantly craft-based teaching approaches to incorporate design principles and mathematical, technical, research and digital skills in executing tasks.

Correspondingly, the training of TVET teachers in Zimbabwe has evolved to equip them with vocational didactic skills relevant to a more problem-solving and technology-driven approach to the delivery of lessons (MoPSE 2024). Hence, this paper explores the vocational didactics predominantly emphasised in delivering construction technology subjects for school TVET curricula in Zimbabwe, particularly those didactical approaches outlined in the Heritage Based Curriculum (HBC) documents of 2024-2030.

1.1 Objectives of this paper

The paper aims to determine factors that influence the vocational didactics used in delivering construction technology-related subjects at the school level in Zimbabwe. It also analyses the principles of vocational didactics used in the delivery of construction technology-related subjects. Lastly, it examines the efficacy of the vocational didactics employed in the teaching of construction technology-related subjects to achieve curricular aims.

1.2 Construction Technology Subjects

Construction technology-related subjects have different names in different countries to achieve their socio-economic goals. For instance, in South Africa, Civil Technology (CT) focuses on a combination of Construction, Civil Services, and Woodworking. CT covers both the practical skills and the application of the technological process. CT advocates for a sound technical base that integrates theory and practical competencies (Department of Basic Education 2014). The subjects aligned to construction technology in Zimbabwe schools’ curricula include Building Technology, and Design, and Wood Technology and Design. The subjects are examined at Form 4 and 6 at the secondary school level. At the school level, the subjects are meant to foster positive attitudes in students towards practical work and equip them with basic practical competencies and the use of tools needed for further training. The nomenclatures changed from Building Studies and Woodwork, respectively, to add “technology and design” in the names from 2015 as a shift from craft-based to technological vocational subjects (MoPSE 2024). The new curricula have adopted competency-based curricula principles to ensure that learners acquire and are tested on the knowledge and competencies required to pass (Goredema et al. 2024).

Other notable curricular changes to the school TVET curricula in Zimbabwe are a result of the Commission of Inquiry into Education and Training (CIET) of 1999 that recommended a secondary school curriculum with a strong vocational component to produce citizens who can apply their technical skills in real life (Coltart 2012; Dube et al. 2018). The changes are evident in the curricular aims and proposed didactical methods stated in the Building and Wood Technology and Design curricula documents. Curricular changes to school vocational education in Zimbabwe have now been rolled out in some national developmental agendas such as the Education 4.0, now 5.0, to implement the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry into Education and Training (CIET) of 1999. The Education 5.0 doctrine is intended to modernise and industrialise the country through education and technology whilst addressing the country’s future workforce skills requirement. Therefore, it can be noted that, indeed, school TVET is used to prepare the learners, starting at the school level, with sustainable technical skills for socio-economic roles and development (UNESCO 2017).

To drive the curricular innovations, Zimbabwe introduced the Heritage-Based Curriculum (HBC) to run from 2024-30, which underpins Education 5.0. This philosophy focuses on using local resources to promote innovation and industrialisation (Government of Zimbabwe 2022). The HBC 2024-30 document stipulates that learners must acquire specific competencies that include “knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and positive dispositions” (ibid). Therefore, teachers delivering construction technology-related subjects are expected to contextualise vocational didactics that promote such skills in an inclusive and meaningful way to enhance students’ experiences (Mukawu 2022).

1.3 Factors that influenced the vocational didactics used construction technology delivery

The vocational didactics recommended by the HBC in the delivery of construction technology shifted from craft-based strategies that emphasised acquiring mainly hands-on skills from 1980 (independence) to 1990 (Zvobgo 1994; Mupinga et al. 2005) to problem-solving and research-based strategies. The vocational didactics used soon after independence were meant to develop manual skills to improve equity and inclusion among people. After ten years of independence, the didactics were changed to solve the growing unemployment of school leavers (Zvobgo 1994). As a result, this led to the inclusion of design education, entrepreneurship skills development, digitalisation and the use of AutoCAD and automated machines, including CNCs, in the vocational education curriculum (Sithole & Hahlani 2022).

Often, TVET teachers want to combine theory learned in class with practice learned in workshops and laboratories to enhance the understanding of the concepts taught. On the one hand, this allows teachers to use those didactical approaches that bridge the gap from the abstract to stimulate interest and attachment between the learners and the materials used in the subject and the educational process (Dube & Xie 2018). On the other hand, connecting theory and practice in workshops will ensure contextual relevance and applicability to the real world for the students.

The curriculum documents for Building and Wood Technology and Design emphasise using suitable practical didactics that will engage learners with materials and yet develop other skills during practical sessions (MoPSE 2024). For example, learners gain the much-needed psychomotor skills, knowledge and understanding, practical skills and their application, decision-making, and judgement.

2 Methodology

This study systematically reviewed journal articles and curriculum documents on vocational didactics in construction technology education in Zimbabwe published between 1990 and 2024. Articles on vocational didactics in Zimbabwe were searched from Scopus, Google Scholar, JSTOR and government articles on vocational didactics. The Boolean search terms used were “Vocational Didactics” AND “TVET in Zimbabwe” This led to the identification of 70 articles published from 2010 to 2024. Of these, 20 articles could not be included in the study because they did not conform to the set criteria and thus were excluded from the analysis, leaving fifty articles for in-depth analysis. The included articles focused on vocational didactics, Education 5.0, Zimbabwe’s Heritage-Based Curriculum, and problems of teaching construction-related vocational subjects. In addition to journal articles, the study examined curriculum documents such as syllabi and government policies on school TVET. These were selected to evaluate official perspectives on vocational didactics in subjects like Building and Wood Technology Design. The empirical research from Zimbabwe shed light on didactical methods in construction technology education. The study also considered the principles of vocational didactic developed through the didactic triangle of Hudson and Meyer (2011), which shows the relationship of the content, learner, and resources. This multi-dimensional analysis established the conceptual framework for understanding the vocational didactics used in Zimbabwe. Other international publications on vocational didactics in construction technology were also considered in order to compare practices with those from other countries.

3 Discussion

3.1 Evolution and Structure of the Vocational Education System in Zimbabwe

The vocational education system in Zimbabwe has evolved through two significant phases: the pre-independence and post-independence periods, reflecting the nation’s changing socio-economic aspirations (Munetsi 1996). Before independence on April 18, 1980, vocational education was primarily controlled by missionaries, who implemented a religious-political curriculum designed to produce semi-skilled workers aligned with colonial labour market needs (Mandebvu 1994; Zvobgo 1994). From 1960, missionary efforts integrated European education systems with church-supported training centres, offering construction-related training in bricklaying and carpentry (Zvobgo 1994). The didactical approaches emphasized the acquisition of competencies needed in the labour market for production. The system facilitated the direct transition of school leavers to employment or apprenticeship programs (Munetsi 2016). However, the system of education was criticized for prioritising semi-skilled labour over fostering creativity and critical thinking (Zvobgo 1994).

Post-independence reforms introduced in 1980 aimed to align vocational education with the new national ideology, which embraced issues of equity, inclusivity, and development. The Education Act No. 5 of 1987, amended in 1991 and 2004, provided the legal framework for guiding primary and secondary education. This legislation emphasised free and compulsory primary education, decentralising educational management, expanding teacher training, and eliminating racial discrimination (Dube et al. 2018).

3.1.1 Integration of Vocational Education in Schools

Post-independence, Zimbabwe adopted a 9-4-2 education structure. Primary education spans nine years, divided into infant education (four years) and junior education (five years). At the end of Grade 7, students undergo assessments marking the end of primary education (Coltart, 2012). Technical education begins in the upper grades of primary school and continues through advanced-level secondary education. The didactical approaches used in the practical subjects at this level are meant to orient learners to the use of tools and various vocations without emphasising competencies.

In line with Policy Circular Number 77 of 2006, all secondary schools must offer at least one technical subject (Ministry of Education Sports Art and Culture 2006; Nherera 2018; Mhlanga et al. 2021). ZIMSEC assesses practical subjects offered in primary and secondary schools, while well-equipped secondary schools provide National Foundation Courses (NFC) managed by HEXCO, the Higher Education Examinations Council (Dube & Xie 2018; Mhlanga et al. 2021). The NFC is a pre-vocational qualification with more emphasis on skills training and the acquisition of competencies to the level of semi-skilled workers.

In 2023, Zimbabwe introduced technical high schools to develop industrial skills, emphasising innovation and entrepreneurship. These schools aim to produce job creators, rather than job seekers, with qualifications equivalent to Advanced Level certificates, enabling university progression (Moyo 2023).

3.1.2 Curriculum and Subject Offerings

Vocational education in Zimbabwe is rooted in Competency-Based Training (CBT) principles to ensure practical, industry-relevant skills. Foundational technical subjects related to the broad category of construction technology include Building Technology, Wood Technology, and Technical Graphics and Design. Building Technology is widely available, even in rural schools, due to its minimal equipment requirements. However, Wood Technology is limited to well-resourced schools due to high equipment costs and electricity constraints needed to drive the workshop or laboratory machinery (Ramaligela et al. 2019).

3.1.3 Initial Vocational Education and Training

Zimbabwe’s Initial Vocational Education and Training (I-VET) system operates through two pathways aligned with the Zimbabwe National Qualifications Framework (ZNQF). The first pathway, managed by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, involves practical tasks, coursework, and competency tests, with final exams conducted by ZIMSEC. The second pathway, overseen by the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, involves the Pre-Vocational Certificate (PVC) and National Foundation Certificate (NFC), administered by HEXCO (Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development 2018). The PVC offers introductory training for Grade Seven students, preparing them as operatives with essential technical skills. The NFC provides intermediate training over two years to Forms 3 and 4 students, equipping graduates to be semi-skilled to assist skilled workers. NFC graduates can progress to technical colleges or undergo trade testing to qualify as Class 4 skilled workers, enabling them to enter the labour market (Dube & Xie 2018).

3.1.4 Construction-Related Vocational Training

The HEXCO pathway includes construction-related subjects tailored to various roles in the industry. These include Brick and Block Laying, Carpentry and Joinery, Cabinet Making, Plumbing and Block Laying, and Decoration and Painting (Dube & Xie 2018).

3.2 Delivery of Vocational Training

Vocational training combines classroom instruction with practical experience. Schools and Vocational Training Centers (VTCs) offer workshops where learners develop hands-on skills, while industry placements provide real-world exposure through internships and attachments to construction firms.

3.3 Principles of Vocational Didactics Used in the Delivery of Construction Technology

The vocationalist perspective argues that the role of education is seen as the preparation of members of society for socio-economic roles through the acquisition of work-related skills and the right attitudes towards work (Mandebvu 1994). The chosen didactics must connect elements of teaching and learning, theory and practice, to make the education process coherent and meaningful (Dube & Xie 2018; Lampiselkä et al. 2019). Students leaving school, in addition to general education, should be trained in specific jobs so that they can proceed directly to employment or self-employment (Nherera 2014). This is also meant to link the education system and the job market, bringing relevance to the education system. The Zimbabwe Heritage Based Curriculum (HBC) 2024-30 document calls upon the TVET teacher to have both the subject technical and pedagogical skills to manage a class, create a conducive and inclusive environment for learners to acquire their technical competencies, values, and life skills (MoPSE 2024). The main competencies emphasised by the HBC include “cognitive competencies, technical, digital and socio-emotional skills”. The basic skills that are meant to drive the five major pillars of the Education 5.0 doctrine are teaching, research, community service, innovation, and industrialisation (Government of Zimbabwe 2016). The same skills are also supposed to permeate through the construction of technology-related subjects’ curricular documents, which are used daily, and the vocational didactics used by TVET teachers to help learners acquire the envisaged skills articulated in Education 5.0.

3.4 Vocational Didactical Teacher Skills

Vocational teachers must possess specific technical knowledge and skills, pedagogical abilities, classroom management expertise, and an understanding of philosophical, sociological, and psychological foundations to effectively teach and manage students (Diep and Hartman 2016). In Zimbabwe, TVET teachers must have the required professional pedagogical qualifications with vocational or technical expertise to deliver practical and technical education. Their vocational or technical qualifications typically include a National Diploma (Level 4) or Higher National Diploma in construction-related trades such as Building Technology, Civil Engineering, Carpentry, Electrical Engineering, Plumbing, or Road Construction. These qualifications focus on the technical competencies required to teach specialised subjects. Teachers may also hold trade certificates in areas like bricklaying, carpentry and joinery, plumbing or wood technology (Chikwature & Oyedele 2018).

In addition to technical skills, pedagogical training is essential for TVET teachers. This includes qualifications such as a Diploma in Education, a teaching diploma offered by the University of Zimbabwe or a Further Education Teaching Diploma (FETD), a teacher’s technical education diploma. These programmes equip teachers with effective teaching methodologies and classroom management strategies while emphasising vocational pedagogies to enhance lesson delivery during teacher training ((Chikwature & Oyedele 2018).

TVET teacher training in Zimbabwe also emphasises fostering professional competence and expertise. The Learning and Assessment Teachers’ Guide (MoPSE 2024), developed under the HBC (2024–2030) framework, outlines aims and objectives for guiding teachers and students. It aims to ensure pupils acquire life and work competencies while promoting an inclusive and supportive learning environment. Objectives include helping students acquire knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes, applying competencies to solve real-world problems, fostering creativity and innovation, and monitoring learner progress in developing 21st-century skills.

TVET teacher training programmes provide a balance of teaching and technical skills, supported by practical industry experience (Mawonedzo et al. 2020). Teachers are trained in interactive methods such as hands-on activities, simulations, and project-based learning. Additionally, they gain entrepreneurial and digital skills, including proficiency in tools like CAD, ensuring they are well-prepared to meet contemporary educational and industry demands.

The Learning and Assessment Teachers’ Guide (MoPSE 2024), which has been developed to guide further the implementation of HBC (2024-2030), states some of the following aims and objectives for students and teachers, respectively:

Aims:

- ensure that pupils’ learning is geared towards acquiring competencies for life and work.

- guide teachers to provide an inclusive and conducive environment for learning and assessment.

Objectives:

- facilitate pupils’ learning of knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and positive dispositions.

- foster the application of acquired competencies and innovation to solve the pupils’ family, community and national problems.

- provide an inclusive and conducive environment for school-based continuous learning and school-based continuous assessment.

- monitor learner progress in relation to development of 21st century skills.

- assess competencies critical for problem-solving, creativity and innovation.

- evaluate pupils’ abilities to apply what they have learnt in real life skills.

TVET teacher training programmes in Zimbabwe provide student teachers with both teaching and technical skills. They gain strong knowledge in their fields, supported by real-world industry experience (Mawonedzo et al. 2020). Along with technical skills, they learn how to use interactive teaching methods like hands-on activities, simulations, and project-based learning. Student teachers also receive training in entrepreneurship and digital skills, such as using CAD (ibid).

3.5 Problem-solving teaching approaches

Problem-solving is one of the suggested learner-centred didactical approaches recommended to vocational teachers for construction technology-related subjects in Zimbabwe. This approach empowers the student by making them active in the learning process, engenders autonomy for the student, and helps them acquire lifelong skills in the process (Farrant 1980). In using the problem-solving teaching method, the teacher’s role is to guide the student and act as a resource person in the learning process. The learner’s creativity is given free rein as they try out their ideas (Nherera 1990).

The problem-solving method is meant to equip learners with the knowledge and skills intended to make them apply what they have learnt to solve real-life problems in their work environment and life. Through this approach, vocational education becomes more relevant. Construction technology always presents many unique and challenging situations that require learners to apply principles learned in different academic subjects to resolve the problems at hand. Therefore, in the teaching and learning process, the teacher must give learners challenging tasks to stimulate the application of scientific and technological knowledge while they solve their assigned tasks (MoPSE 2015).

Construction Technology teachers must apply those didactical approaches that enhance the achievement of the aims and objectives stated in the syllabus. Some of the aims stated in the Building and Technology and Design Syllabus (2015-2022) at the school level include (MoPSE 2015):

- to prepare learners for life and work in the economy and global world.

- to ensure learners acquire and demonstrate literacy and numeracy skills, including practical competencies necessary for life.

- to enhance the use of Information and Computer Technology (ICT) in teaching Building Technology and Design.

Similarly, Wood Technology and Design Syllabus (2015-2022) (MoPSE 2015) at the school level also include the following aims:

- design useful projects as solutions to problems using technologies

- apply scientific principles and technology to solve real-life problems

- make, care and maintain tools and equipment used in Wood Technology and Design

The new curriculum framework of 2015 to 2022 introduced a new dimension to the problem-based learning approach named Continuous Assessment Learner Activities (CALA). CALA is an approach that promotes research and experiential learning, encouraging learners to take an active role in the educational process (Gama 2022). From 2024, CALA has been replaced by School-Based Continuous Learning (SBCL) projects (MoPSE 2024). In line with the dictates of HBC, construction technology-related subjects have increasingly adopted Problem-Based Learning (PBL) methodologies to reflect the problem-solving nature of construction work. For instance, every year, completing students receive a design problem set by ZIMSEC where they are tasked with resolving construction-related challenges, which include sustainable building practices, cost estimation, materials selection, and simulating and requiring them to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts. Through this design process, students acquire various skills from technical, traversal and soft skills (MoPSE 2015).

Vocational teachers are, therefore, expected to have adequate technical and pedagogical skills to effectively deliver the vocations to meet the long-term goals of the syllabi and the curriculum framework (Goredema et al. 2024). The didactical approaches may differ depending on whether it is a theoretical or a practical lesson. Despite the different didactic approaches applied, teachers must ensure that learners develop socially, physically, emotionally and cognitively (MoPSE 2015).

3.6 Design teaching approaches

The current construction technology-related subjects have a strong component of school-based design projects which all students must do as part of their continuous and terminal examinations (MoPSE 2015). In the examination system, the design component makes up Paper 3 of the assessment process, and students are required to come up with designs that try to solve an existing problem at a relatively cheaper cost of materials, labour and time (Hondonga 2007). The projects are also meant to encourage students to engage hands-on with materials and tools in the design process, analyse, synthesise, and apply all knowledge learnt to solve a practical problem. According to Kimbell (1982), the basic principles of the design process foster creative thinking, problem-solving, and inventive skills as students are given the freedom to create something that interests them and is very much their own. The teacher’s main role in the design process is to act as a facilitator guiding the student through a systematic process (MoPSE 2024).

Vocational teachers are, therefore, expected to have good mentoring and coaching skills amongst other didactic skills. Since design education puts the student at the centre of the learning process, it adds value and relevance to what they learn and gain lifelong skills. The vocational teacher should allow the student to gain artistic skills, engineering, innovation, mathematics, technical skills, interdisciplinary skills, and critical thinking skills, amongst many other skills (Nherera 1990). Throughout the design cycle, the design caters for individual differences and promotes curiosity, persistence, imagination, uniqueness and self-confidence in learners. At the end of the process, the teacher must objectively apply assessment skills to determine how much the learner knows (knowledge), how efficiently they perform skills (competencies), and what convictions they hold after the entire process (values and attitudes) (Hondonga 2007). Therefore, a construction technology teacher must have a wide variety of pedagogical and assessment skills.

3.7 Inclusive Vocational Didactics in Construction Technology

Target 4.5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) clearly states that there must be a deliberate effort to ensure equal access to vocational training for all people at all levels (ILO 2017). Despite the louder calls for inclusive actions to address all forms of exclusion and marginalisation, disparities and inequalities that undermine access and participation in vocational education, construction vocational teachers still face challenges to fully achieve this because of the nature of the vocation (Chinengundu & Hondonga 2024; Mukawu 2022). For example, Building Technology and Design at the school level involves practical lessons requiring students to do manual work that requires students to be agile and constantly move. Some practical lessons require learners to get onto some precarious positions on scaffolds, which may not be possible for some learners who may have impaired mobility (Mosalegae & Becker 2021). In Wood Technology and Design, some learners may have limited access to operate some of the machinery. This is although the Building and Wood and Technology and Design syllabi state that there must be equitable access to vocational training for all learners regardless of gender and different physical abilities (Mukawu 2022). Therefore, some learners become indirectly excluded due to the rigid curriculum designs and limited capacities to adapt to the various and often rigid pedagogical methods (Maggiolini & Molteni 2013; Molosiwa & Mpofu 2017).

Svendby (2020) found that, on the one hand, even in situations where schools may want to mitigate pedagogical exclusions, most schools cannot afford the specialised equipment. On the other hand, a study by Mosalegae & Becker (2021) found that the majority of TVET teachers may not have basic inclusive pedagogy skills in their teaching to suit the needs of learners with diverse needs. In another study conducted in Zimbabwe, Mukawu (2022) found that teachers appreciated the need for inclusion in Building Technology and Design as this learning area could potentially empower all learners, including those with disabilities, with survival economic skills.

4 Conclusions

The systematic review found that the changing skill set demands to be included in the construction vocations also influence the vocational didactics teachers deployed in the classroom. Further findings suggest that TVET trainee teachers are equipped with technical skills and trained in using interactive teaching methods like hands-on activities, simulations, and project-based learning. Student teachers also receive training in entrepreneurship and digital skills to deliver lessons using digital technologies. It has been established that TVET teacher training programmes must be continuously revised to meet the skill dynamics required by learners who have to fit into a fast-changing labour market. Problem-solving and design teaching approaches are heavily emphasised in construction technology subjects at the school level in Zimbabwe. Several other teaching approaches are also recommended to ensure that students acquire technical, traversal and soft skills. Design and problem-solving approaches are meant to foster creative thinking and inventive skills as students are free to create novel and original ideas. The didactic approaches emphasised in the continuous assessment projects are intended to encourage students to engage hands-on with materials and tools in the design process. Students learn to critically analyse situations and their work, synthesise, and apply all knowledge learnt to solve a practical task. Despite the different didactic approaches applied, teachers must ensure that learners develop socially, physically, emotionally and cognitively. Therefore, a construction technology teacher must have a wide variety of pedagogical skills for learners to acquire lifelong skills. It can be noted that due to rigid pedagogical methods, some learners become indirectly excluded from taking up construction technology-related subjects at the school level. The reviewed literature suggests that the majority of TVET teachers in Zimbabwe may not have basic inclusive pedagogic skills to suit the needs of learners with diverse needs.

5 Recommendations

Vocational teachers need to keep abreast of sustainable technological advancements in modern green construction workplaces to enhance the relevance of their didactical approaches. The greening of construction technology teachers’ didactic and pedagogical skills must improve the acquisition of the green skill sets of construction industry practices and curricula. Teachers must have the tools to evaluate their delivery skills honestly so that staff development interventions can be put in place to avoid skills transfer gaps. Regular curricular reviews for pre-service and in-service TVET teacher training programmes must be undertaken with industry advisory bodies so that teacher didactic competencies remain current in this era of sustainable development. There is a need to have routine staff development activities to equip TVET teachers with modern and emerging improvements to didactic approaches needed for green skills and jobs so that teacher skills do not become obsolete. To improve the inclusive participation of all learners with diverse needs, there is a need to include modules on inclusive pedagogics for trainee teachers to develop their capacity to handle learners with diverse needs. Vocational teachers must also be empowered to deliver the subjects using blended learning approaches to build capacity in learners to use computer applications in design and future skills needed in the modern construction workplace, which will involve several software.

References

Berglund, A. & Lister, R. (2010). Introductory Programming and the Didactic Triangle. In: Proc. In: IFAC Symposium on Advances in Control Education.

Chikwature, W. & Oyedele, V. (2018). Factors Contributing to Low Enrolment Levels of Further Education Teacher Training Diploma in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. In: Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 2(10), 798-802.

Chinengundu, T. & Hondonga, J. (2024). Inclusive education practices in TVET institutions in Botswana, South Africa and Thailand: A systematic review. In: TVET@Asia, issue 23, 1-23. Online: https://tvet-online.asia/startseite/inclusive-education-practices-in-tvet-institutions-in-botswana-south-africa-and-thailand-a-systematic-review/ (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Coltart, D. (2012). Education for Employment: Developing skills for Vocation in Zimbabwe. Presented at the African Brains Conference at the University of Cape Town (5-7 October 2012).

Department of Basic Education (2014). Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (Caps) Grades 10 – 12. Civil Technology. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education of the Republic of South Africa.

Department of Teacher Education (2010). Building Technology Syllabus. Harare: University of Zimbabwe.

Diep, P.C. & Hartmann, M. (2016). Green Skills in Vocational Teacher Education – a model of pedagogical competence for a world of sustainable development. In: TVET@Asia, issue 6, 1-19. Online: https://tvet-online.asia/startseite/industry-and-vocational-school-collaboration-preparing-an-excellent-and-industry-needed-workforce/ (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Dube, N.M. & Xie, S. (2018). The development of technical and vocational education in Zimbabwe. In: Journal of Progressive Research in Social Sciences (JPRSS), 8(1), 614-623.

Farrant, J.S. (1980). Principles and Practice of Education. London: Longman.

Gama, S. (2022). An assessment of the implementation of Continuous Assessment Learning Activity in secondary schools in Chirumanzu District, Zimbabwe: A case of Hama High School. In: Indiana Journal of Arts & Literature, 3(3), 23-26.

Goredema, R., Chakamba, J., & Chinengundu, T. (2024). Competency-Based Curriculum Implementation in Building Technology and Design in Zimbabwe’s Secondary Teachers’ Training Colleges: Stakeholders’ Perceptions. In: International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), VIII(IIIS), 3264-3280.

Hondonga, J. (2007) The place of problem solving in the teaching of Design Education. In: The Teacher’s Voice in Zimbabwe, 2, 29-30.

Hudson, B. & Meyer, M. A. (2011). Beyond fragmentation: Didactics, learning and teaching in Europe. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2017). Making TVET and skills systems inclusive of persons with disabilities. Online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_emp/%40ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_605087.pdf (retrieved 21.01.2025).

Kimbell, R.A. (1982). Design Education: The Foundation Years. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd.

Lampiselkä, J., Kaasinen, A., Kinnunen, P., & Malmi, L. (2019). Didactic focus areas in science education research. In: Education Sciences, 9(4), 294.

Langford, M., Maruco, T., & Tierney, W.G. (2015). From Vocational Education to Linked Learning: The Ongoing Transformation of Career-Oriented Education in the US. Online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315760035_From_Vocational_Education_to_Linked_Learning_The_Ongoing_Transformation_of_Career-Oriented_Education_in_the_US (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Maggiolini, S. & Molteni, P. (2013). University and disability. An Italian experience of inclusion. In: Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26(3), 249–262.

Mandebvu, O.S. (1994) Grappling with Dichotomy of Youth Unemployment and the Education Needs of a Developing Economy: The case of Zimbabwe. An unpublished paper presented at the 16th Comparative Education Society in Europe (CESE) Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Mawonedzo, A., Tanga, M., Luggya, S., & Nsubuga, Y. (2020). Implementing strategies of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwe. In: Education+ training, 63(1), 85-100.

Mbongwe, J. (2018). Graduate employability and Higher Education Responsiveness: The debate rages on. In: Sunday Standard. Online: https://www.sundaystandard.info/graduate-employability-and-higher-education-responsiveness-the-debate-rages/ (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Mhlanga, M., Tenha, J., & Ndhlovu, F. (2021). Technical and Vocational Education and Training Policy in Zimbabwean Secondary Schools: Teachers’ Views. In: International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, 8(7), 111-118.

Ministry of Education Sports Art and Culture (2006). Directors Policy Circular Number P 77 of 2006. Harare: Government Printers.

Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development (2018). Zimbabwe National Qualifications Framework. Online: http://www.zimche.ac.zw/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ZNQF.pdf (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (2015). Building and Technology and Design Syllabus. Harare: Curriculum Development and Technical Services Department.

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) (2015). Curriculum Framework for Primary and Secondary Education 2015-2022. Harare: Government Printers.

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) (2015). Wood Technology and Design Syllabus. Harare: Curriculum Development Unit.

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) (2024). Learning and Assessment Teachers Guide. Online: https://de.scribd.com/document/770164595/Final-Teacher-s-Guide-to-Learning-and-Assessment (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Molosiwa, S. M. & Mpofu, J. (2017). Practices and opportunities of inclusive education in Botswana. In Phasha, N., Mahlo, D., & Sefa Dei, G.J. (eds.): Inclusive education in African context: A critical reader. Rotterdam: Sense Publisher, 65–84.

Mosalagae, M. & Bekker, T. L. (2021). Education of students with intellectual disabilities at technical vocational education and training institutions in Botswana: Inclusion or exclusion? In: African Journal of Disability, 10(0), a790.

Moyo, N. (2023). Governmeny Introduces Technical High Schools. In: Newsday. Online: https://www.newsday.co.zw/local-news/article/200006261/govt-introduces-technical-high-schools (retrieved 31.01.2025).

Mukawu, L.H. (2022). Implementing inclusive education in Building Technology and Design in Zimbabwe Secondary Schools: Challenges and the Way Forward. In: International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 6(1), 803-810.

Munetsi, N.N. (1996). The Development of Technical and Vocational Education in Africa: Case Studies from Selected Countries. Dakar: UNESCO Regional Office Senegal.

Mupinga, D, Burnett, M.F., & Redmann, D.H. (2005). Examining the purpose of technical education in Zimbabwe’s high schools. In: International Education Journal, 6 (2), 75-83.

Muzari, T., Chasokela, D., & Sithole, A. (2022). Computer Integrated Manufacturing Sub-Systems in Technical and Vocational Education and Training: A Bewilderment for Stakeholders in Polytechnics in Zimbabwe. In: Indiana Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(3), 45-53.

Nherera C.M. (2018). Rethinking Technical and Vocational Education and Training in the Context of the New Curriculum Framework for Primary and Secondary Education 2015-2022 in Zimbabwe. In: Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 30(1).

Nherera, C. (1990). Design Education and the Teaching of Woodwork at Secondary School Level in Zimbabwe. In: Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, ZJER, 2 (3).

Nherera, C. (2004). Vocationalisation of Secondary Education in Zimbabwe: An examination current policies, options and strategies for the 21st century. In: Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research (ZJER), 26 (2).

Nore, H. (2015). Re-contextualizing vocational didactics in Norwegian vocational education and training. In: International journal for research in vocational education and training, 2(3), 182-194.

Nziramasanga, C.T. (1999). Commission of Inquiry into Education and Training. Report on the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Education and Training. Harare: Government Printers.

Ramaligela, M.S., Makgato, M., & Hondonga. J. (2019). A comparison study of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in SA, Zimbabwe, and Botswana. In Arko-Achemfuor, A., Quan-Baffour, K.P., & Addae, D. (eds.): Adult, Continuing and Lifelong Education and Development in Africa. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers.

Sithole, S. & Hahlani, O.S. (2022). Teacher Concerns on the Uptake of Auto-CAD in the Teaching of Building Drawing in Zimbabwe Secondary Schools: A Case of Masvingo District. In: Indiana Journal of Arts & Literature, 3(10), 1-8.

Svendby, R. (2020). Lecturers’ Teaching Experiences with Invisibly Disabled Students in Higher Education: Connecting and Aiming at Inclusion. In: Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 22(1), 7–12.

UNESCO (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. Paris: UNESCO. Online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (retrieved 21.01.2025).

White, P.J., Tytler, R., Ferguson, J.P., & Clark, J.C. (eds.) (2022). Methodological Approaches to STEM Education Research, Volume 3. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Zvobgo, R.J. (1994). Colonialism and education in Zimbabwe. Harare: Sapes Books.