Abstract

With the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 and the simultaneously increasing challenges in society and the world of work (digital transformation, greening), a supranational regional approach to TVET governance in Southeast Asia has become a more pressing issue. This joint approach to governance of TVET allows actors and organisations to act flexibly and innovatively according to the principles of self-direction, oriented to the needs of a regional labour market in terms of effective, efficient, equitable, inclusive and sustainable vocational education. To date, this has been countered by the structural and historical weaknesses of the Southeast Asian Association of Nations. Nevertheless, in the past decade – notably after the creation of the AEC in 2015 – an ASEAN-wide regulatory framework of TVET has been established, culminating in the establishment of the ASEAN TVET Council in 2020 to provide a basis for the development of “good governance”. This essay presents important milestones along the way for organisations and actors, as well as new initiatives and instruments. It concludes by arguing for an expansion of regional TVET research and development, which can support the necessary expansion and design processes in earnest.

Keywords: TVET, good governance, TVET research, ASEAN, ASEAN TVET Council, ASEAN Economic community.

1 Governance as a task in the further development of regional vocational education and training

TVET systems must be flexible because they are constantly called upon to implement changes relating to legal regulations, for example, or to assess and assimilate new technologies which impact on the labour market and vocational education and training. The goal is to provide up-to-date vocational education and training at the highest level of quality. This requires structures and mechanisms that allow actors and organisations to offer vocational education and training in keeping with demand at all times.

Adequate governance is a prerequisite for market-relevant and sustainable development of technical and vocational education and training in the rapidly changing climate of digital transformation. UNESCO highlighted its importance more than a decade ago:

… TVET governance is “concerned with how the funding, provision, ownership and regulation of TVET systems are coordinated, which actors are involved, and what are their respective roles and responsibilities, and level of formal competence – at the local, regional, national and supranational level. Whilst in many countries government continues to play the most significant role in coordinating TVET, the distribution of these responsibilities has been changing in response to calls for greater efficiency and effectiveness, particularly to engage employers.” (UNESCO 2010, 6)

Today, however, governance goes beyond the distribution of competences and responsibilities in the sense of efficient and effective regulation of vocational education and training. According to UNESCO’s new TVET strategy 2022-2029 (UNESCO 2022), in addition to purposeful organisation and governance, it should also pursue the development of (vocational) skills and competencies under the guiding principle of an inclusive, peaceful and sustainable society. The UNESCO Agenda 2030 features 17 Sustainable Development Goals, the fourth of which highlights inclusive, equitable and high-quality education for all.

If we expand the concept of governance a bit further, it is essential to see how it differs from government. Both involve institutionalisations that enable actors to do or regulate things. Whereas government is predicated on authority, however, governance emphasises self-regulation:

“4. Governance is about autonomous self-governing networks of actors. 5. Governance recognises the capacity to get things done which does not rest on the power of government to command or use its authority.” (Stoker 2018, 16)

Cedefop (2016, 33ff; based on Rauner 2009 and own preliminary work) differentiates the governance of TVET systems on system-theoretical lines into four so-called “skill formation regimes”. Depending on how governance (structures, processes, organisations, actors) is distributed in terms of competencies (powers, responsibilities) between the state and the private sector, a distinction can be made: state-centralised, liberal, collective (the German dual model) and segmentary systems. The extent to which actors (subsystems) in this system actually have influence “to get things done” (Stoker) depends on feedback mechanisms, which can be characterised as:

“purposefully implemented institutional procedures that allow TVET (sub-)systems to continuously renew themselves and adapt to emerging labour market needs. … such feedback mechanisms … (are) governmental and administrative bodies, education and training providers, social partner organisations and the labour market.” (ibid., 36f)

Similarly, but with a more action-theoretical orientation, Büchter, Bohlinger, & Tramm (2013) argue that innovation also starts at an institutional level (laws and norms, state structures, cultural standards and traditions) and that innovation comes about when actors with different interests negotiate and establish new institutionalisations in more or less conflictual situations. However, this presupposes structures in which such processes can take place “without interference”, and this, by extension, requires – when processes threaten to become routines – institutionalised mechanisms for decision-making. In Büchter, Bohlinger, & Tramm (2013), this line of argument looks to the German dual vocational training system, where there is a significant commitment to modern design and equal opportunities, but traditional patterns persist in the face of appropriate decision-making paths (impermeability).

Hauschildt & Wittig (2018, 276f; similar in Cedefop 2016, 41) identify six main criteria to assess and describe the governance of a TVET system (a continuum with two poles is indicated in parentheses in each case):

- coordinated legal regulations (coordinated – fragmented)

- distribution of strategic and operational functions (local – central)

- involvement of relevant stakeholders (exclusionary – inclusive).

- quality assurance and development strategies (rigid – dynamic)

- balance of outcome and input orientation (outcome – input).

- partnership financing (state – cooperative)

Using the so-called governance equalizer developed in the example of university administration (Schimank 2007, 238) – an analogy between the regulation of an administrative system and the control of a sound recording in a studio – Hauschildt & Wittig (see above) demonstrate the analytical usefulness of their criteria in an exemplary account of the current German dual model.

TVET governance can also be analysed on meso, micro and macro-levels(UNESCO-UNEVOC 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). The first level refers to the places and institutions where TVET takes place directly (micro), the second to the aggregating organisations at local, regional, and national levels (meso), and the third to the institutions and organisations potentially affecting the entirety of a TVET system: the state, unions, employers (macro). This distinction is a valuably pragmatic one that helps to differentiate stakeholders according to their interests and potential opportunities for influence. They (the stakeholders at all three levels) act together, but with preferences in line with their own characteristics, to shape TVET and are collectively responsible for identifying relevant competencies, incorporating them into curricula and training programmes, and implementing them in learning environments (UNESCO-UNEVOC 2021a, 7). In this regard, “good governance” requires each of the three levels equally; it must allow macro-control in the sense of a justified common good as well as bottom-up strategies by actors – with equally justified interests – at the micro and meso levels. Lower levels need a certain degree of autonomy, as they know the conditions on the ground best, but at the same time they need a framework that opens up opportunities for them to shape things in the first place: “enabling” is the term used by UNESCO.

With regard to regional (supranational) governance, which is the subject of this essay in the form of the joint vocational training of the ASEAN states (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), this does not initially appear to be problematic, since governance by definition is not a government and is not conceptually bound to nation-state (or similarly fixed) borders. But its legal-institutional character (including the possibility of sanctioning) is consistently an important part in functioning governance structures. This implies an affinity to state organisation, or at least the definitions and categorical frameworks point to a nation-state aspect of governance. It is not easy to speak conceptually of common governance in the case of the European Union – especially in the field of (vocational) education and training – since the European Union applies the open method of coordination (OMC). This means that common regulations and initiatives are implemented outside the legal competences of the EU through an exchange of information and the search for best practices (Bauer & Knöll 2003). Joint governance is even more difficult in the case of ASEAN, which continues to follow the ASEAN Way of the association of sovereign nation states even after the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015.

A second point is just as true as the prevalence of nation states in structural institutional and legal terms and, above all, connected through their actors: regions are becoming increasingly important today for the prosperity and welfare of the individual, both socially and economically. Where this is the case, common, functioning governance is required. Work and prosperity are particularly significant variables for social harmony and economic development in regions- necessitating the need for regional TVET governance. For ASEAN, in line with increasing economic integration, there is a need for region-wide coordination or even “joint governance” of TVET. The current constitution of regional TVET governance is not yet at this level, but the way forward has become clearer – all the more so since the establishment of the AEC in 2015. Chapter 2provides an overview of efforts for a common regulatory framework for TVET in the ASEAN region (Schröder 2022; for national TVET systems see Bin Bai & Paryono 2019). Chapter 3 discusses whether regional “good TVET governance” (in an explicitly normative sense) is beginning to emerge – and to what extent.

2 TVET design in the ASEAN region: Actors, Initiatives, Problems

2.1 Basic structures and challenges

ASEAN is far larger than the EU and, since January 1, 2022, part of the world’s largest free trade area (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership). The critical situation in the world today does not seem to have shaken Southeast Asia’s pre-Corona reputation as one of the world’s fastest-growing and most dynamic regions (Flatten et al. 2019), nor – as the last summit in November 2022 showed – has it undermined the confidence of ASEAN leaders in the path they have chosen. None of this could have been foreseen in 1967, when a number of Southeast Asian states were seeking their way to independence after a long period of colonial dependence. Political, economic, social and cultural integration began almost 10 years later with Bali Concord I in 1976 followed by Bali Concord II in 2003, which established the three pillars of ASEAN’s organisational structure: security, economic and socio-cultural – the last of which includes vocational education and training. The economic and financial crises of 1997 and 1998 provided the impetus for further integration efforts. A panel of political figures formulated ASEAN Vision 2020, which became the basis for the ASEAN Charter in 2007. This underpinned the founding documents of the renewed association in 2015: ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together (ASEAN Secretariat 2015).

For all its proclaimed and accomplished integration, ASEAN is still based on its founding principles of “national sovereignty” and non-interference in internal affairs. Joint resolutions are only possible by way of diplomatic consensus – requiring the good will of all to implement them. This “ASEAN Way” is partly responsible for the low level of visible representation, which is limited to meetings of heads of state and government, or at the level of ministers and state secretaries. The Secretariat, established in Jakarta in 1973, is considered weak because of its low level of human and financial resources, owing to the prevalence of national interests (Lay Hwee 2020, 9f; see also Mahbubani 2017).

This founding history of ASEAN should be prefaced by two characteristics that still apply to a (joint regional) design of vocational education and training in the ASEAN region, which intensified with steps toward economic integration and the founding of the AEC. Initial approaches had already taken place in the 1980s with Japan and Australia (Vitić 2020, 711-732):

- Supranational TVET initiatives are merely recommended to the respective institutions of the AMSs (ASEAN Member States) for implementation, such as in the case of the ASEAN Qualifications Framework:

“The ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework is based on agreed understandings between member states and invites voluntary engagement from countries.” (ASEAN Secretariat 2020c)

- ASEAN vocational education and training initiatives are often coordinated by the Secretariat in Jakarta, but are not feasible without other organisations and actors (SEAMEO VOCTECH and others ) or external support (e.g., the GIZ RECOTVET programme).

The problems of ASEAN-wide TVET governance structures are evident here. If these are to be adequately addressed, Southeast Asian challenges which makeregional governance of TVET more difficult must be considered. First, there is the tension that arises from great economic dynamism on the one hand and the immense social and economic disparities between and within countries on the other. The showcase city-state Singapore, wealthy Brunei and the limited prosperity of Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam stand in contrast to the “poor” CLM countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar).

Furthermore, supranational action is hampered by cultural, religious, ethnic, linguistic and political differences – often even within a single country. Forms of government range from the sultanate in Brunei and a parliamentary democracy (Singapore) to de facto autocratic systems (Cambodia) and the current military regimes in Myanmar and Thailand. In addition, the region is more frequently affected by natural disasters (tsunami) than others. “Megacities” such as the 12-million-strong Manila region create environmental problems, and the often-cited advantage of a relatively young population seems to be on the wane. ASEAN is reacting to this with numerous initiatives – one of the most important, the Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI),is currently working on its fourth Work Plan IV (2021-2025).

This identifies important structures and challenges underlying common TVET design in the ASEAN region and opportunities for improved governance. Before the latter can be discussed in Chapter 3, a detailed account of TVET in the ASEAN region must be provided. This encompasses organisations and actors, initiatives and instruments working towards a common regulatory framework, a project that has gathered momentum since 2015.

Three points are worth noting in this context:

- The main ASEAN bodies responsible for regional TVET cover the entire education sector (human resource development).This corresponds to the low level of structural and institutional separation between TVET and higher (university) education.

- Concrete initiatives and projects in vocational education and training are largely carried out by regional organisations and actors in the Asia-Pacific region who act alongside and with ASEAN structures. ASEAN’s institutional and financial weakness is only partly responsible for this; it is also a consequence of traditional patterns regarding vocational education rooted in colonial history.

- Support from external partners is essential for concrete projects to align TVET systems in ASEAN in the course of economic integration. The German RECOTVET programme currently occupies an exposed position, but has not replaced traditionally strong partners (China, Korea, Japan, Australia).

2.2 Organisations and programmes: ASED, SEAMEO, ATC

The most important ASEAN body in the education sector is the ASEAN Education Ministers’ Meeting (ASED), which is supported by a subordinate body at state secretary level, the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Education (SOM-ED), and the Education, Youth & Sports Division from the Human Development Directorate of the ASEAN Secretariat. These bodies are responsible for the entire education sector. TVET comprises only a smaller part of the tasks. There are comparable institutions in the labour ministry with responsibility for TVET.

The most important educational organisation in the Southeast Asian region, the Southeast Asia Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO Secretariat 2021), must also be counted among ASEAN’s own institutions. Although it is not officially an organ of ASEAN, in terms of personnel it is largely similar to ASED and functions de facto as its operational arm. Also responsible for the entire range of education, SEAMEO operates 26 centres of expertise spread across all ASEAN countries. The Regional Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (SEAMEO VOCTECH) in Brunei Darussalam has been in operation since 1990; the Regional Centre for Technical Education Development (SEAMEO TED) in Cambodia (Phnom Penh) was added in 2017.

Before 2015 (establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community), there was only one de facto state institution dedicated exclusively to regional TVET: the Brunei Technical Center. As integration efforts advanced and demands on the global labour market intensified (Industry 4.0), TVET initiatives in the region increased (see 2.3) and TVET gained programmatic weight in the joint declarations of ASEAN. Finally, in 2020, the ASEAN TVET Council (ATC) emerged as the first ASEAN-owned institution exclusively responsible for regional TVET, composed of its key stakeholders at the policy level: representatives of the Ministries of Economy, Labour and Education of all ASEAN countries, SEAMEO, the ASEAN Future Workforce Council (AFWC), the ASEAN Confederation of Employers (ACE) and the ASEAN Trade Union Council (ATUC). According to its statutes, the new body is to promote sustainable vocational education and training and to better coordinate and harmonise initiatives of the stakeholders active in the region (see 2.3):

“Currently, TVET and skills development in many AMS are handled by several ministries and, at the regional level, by several ASEAN sectoral bodies. Furthermore, many training institutions, private companies, international organisations and other stakeholders in the region have been collaborating to enhance TVET access, quality and relevance. Better coordination and sharing of information among stakeholders can help to address the aforementioned challenges.” (ASEAN TVET Council 2020)

In its first Work Plan for 2021 to 2030 (ASEAN TVET Council 2021), the Council articulated guiding objectives of a modern TVET programme, including:

- Strengthening labour market orientation through effective evaluation of labour market data and institutionalised cooperation with the business sector;

- Improving all capabilities (including digital) of the TVET system to accommodate and respond to emerging trends;

- Increasing the capacity of TVET personnel (policy makers, managers, teachers, trainers in schools, centres and enterprises);

- Raising the image and status of vocational education and training to boost interest in vocational education and training in AMSs and ASEAN as a whole;

- Harmonising an ASEAN-wide TVET system.

The ASEAN TVET council (ATC) thus follows on from specifications in two documents that express the increased relevance of TVET in the ASEAN region. One is the current guiding declaration for the entire education sector: the ASEAN Declaration on Human Resources Development for the Changing World of Work and its Roadmap (ASEAN Secretariat 2020a), which formulates a 15-point HRD policy geared to the requirements of today’s companies and labour markets (see also ASEAN Secretariat 2021a). Secondly, the ASEAN Work Plan on Education 2021-2025 (ASEAN Secretariat 2021b) goes into greater detail on vocational education and training. Here, a guiding objective (to increase the quality of TVET according to the changing demands of the labour market) is assigned sub-objectives that resemble those in the ATC Work Plan (stronger cooperation with the private corporate sector, further training of TVET personnel, for example); one explicitly addresses governance: “Strengthen regional cooperation and exchanges on TVET governance and TVET systems reform.” SEAMEO has a similar work plan (SEAMEO Secretariat 2020).

However good and ambitious the work plans of the ASEAN institutions may be, projects would hardly be feasible without partners or external (financial) support. This is a very important aspect of the ASEAN vocational training landscape.

2.3 ASEAN partners, initiatives and instruments in the development of regional vocational education and training

Regional TVET initiatives in the ASEAN region are largely borne by organisations and actors outside or alongside ASEAN structures. Although the Secretariat in Jakarta coordinates projects and the Ministers of Education (ASED) formulate guidelines, concrete regional TVET initiatives are mostly undertaken by other organisations, the majority of which (such as ASED and SEAMEO) are active in all education sectors, some predominantly in higher education. TVET features to a lesser degree in the Southeast Asian region in this context.

SEAMEO VOCTECH and SEAMEO TED are two specialist institutes that are exclusively active in vocational training (in the broad sense). Both offer various training measures (including online), issue publications and organise events to encourage dialogue in strategic orientation. The institute in Brunei is involved in many topics of modern vocational training, including the development of curricula, quality enhancement for teachers, information and communication technology, and research (SEAMEO VOCTECH 2021). The younger SEAMEO TED offers mainly International Training Courses (SEAMEO TED 2021).

In addition to these two institutes, there are three other organisations with their own profiles. The ASEAN University Network (AUN) – officially a subordinate ASEAN authority – promotes academic and professional resources in the region through exchange and cooperation, with TVET playing a rather subordinate role. The Colombo Plan Staff College of Technicians Education (CPSC) is explicitly dedicated to improving teaching in TVET institutions and publishes training manuals on various topics (curriculum development, greening TVET). The Regional Association for Vocational and Technical Education (RAVTE), founded in 2014, which comprises 26 universities is active in the education of TVET teachers, promotes TVET research and Vocational Education as a self-reliant academic discipline as a precondition for research-based development (Schröder 2017a; 2017b; 2019a; 2019b; RAVTE 2015).

The major international organisations with TVET-related activities are also present in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Of particular note is the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Regional Bureau of Education in Bangkok, which is the regional UNESCO representative responsible for the Education Agenda 2030 and the UNESCO TVET Strategy (UNESCO 2022), and a broad variety of UNESCO UNEVOC Centers.

The RECOTVET programme (Regional Cooperation Program to Improve the Quality and Labor Market Orientation of Technical and Vocational Education and Training) is currently one of the most important external pillars including cooperation with SEAMEO VOCTECH. It operates in four key areas: strengthening regional institutions (ATC!); quality assurance; cooperation of TVET with business and industry; and improving the qualifications of training personnel. The PRC and the Republic of Korea, which form the ASEAN+3 format with the ASEAN countries and further strengthened their cooperation in the RCEP Free Trade Agreement (2022), continue to be important partners in TVET. Australia, the first ASEAN dialogue partner to launch an education initiative back in the early 1980s, started the Education & Training to manage fast-growing cities project in 2018.

Among the TVET initiatives with a clear regional focus that are being pursued by these organisations and stakeholders alongside and with ASEAN are two information-sharing and networking projects led by SEAMEO VOCTECH: the Regional Knowledge Platform for TVET in Southeast Asia (SEA-VET.net), established in 2017, and the SEA TVET Consortium, launched back in 2015 by the SEAMEO Secretariat, an alliance of education providers, vocational schools, and companies that sees itself as an exchange forum for TVET leaders and institutions.

Under the maxim of an integrated economic area, however, instruments that raise the quality of vocational education and training, strive for comparability of certifications and promote professional mobility, played an even more central role. A number of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) concluded between 2005 and 2014 are worth noting. Regional standards for vocational qualifications are set by the ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework of 2014 (ASEAN Secretariat 2020c), comparable to the EQF (European Qualifications Framework). For quality assurance, an Australian-sponsored framework for TVET was developed, which later became the reference point for further measures: the EAST ASIA SUMMIT Vocational Education and Training Quality Assurance Framework (Bateman et al. 2012). An ASEAN Quality Assurance Framework including guidelines for external evaluations has been available since 2020 in a 2.0 version (ASEAN Quality Assurance Network 2020). The Asia Pacific Accreditation and Certification Commission (APACC), led by the Colombo Plan Staff College, certifies regional TVET institutions.

The training of teaching staff for vocational schools and companies remains a key objective. With the support of SEAMEO VOCTECH and RECOTVET, Matthias Becker and Georg Spöttl (Becker & Spöttl 2019a; 2019b; 2020) produced three papers that define regional standards for TVET teachers, determine guidelines for the elaboration of TVET disciplines, and establish principles for quality assessment in the work of TVET teachers. The Standards for In-Company Training in ASEAN countries, published in 2015, is a milestone developed by a group of experts with support from RECOTVET, formally adopted by ASEAN bodies (GIZ-RECOTVET 2019), and already tested in national implementation for Thailand by the Thailand Professional Qualification Institute (Seel & Komuthanon 2020). The third funding phase of the RECOTVET programme (which runs until 2023) follows on from this, with projects in Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam.

3 On the way to “good governance”? ATC, Regional TVET Research and the Development of TVET in ASEAN

“Work-based learning programmes will be ineffective in driving TVET reforms if they are not complemented by policy measures to change institutional arrangements, e.g., governance (bold type by author) and social partner roles and responsibilities.” (Chakroun 2019, 314)

Chakroun’s assertion once again seems to have reached the actors of the vocational training sector in ASEAN. Efforts to improve regional TVET can be read in this sense: economic integration requires better TVET, and this in turn implies changes in institutional arrangements, in the roles and responsibilities of all partners. Understood as a demand for better ASEAN-wide TVET governance, the establishment of the ASEAN TVET Council 2020 is an attempt to meet this:

“The ASEAN TVET Council (ATC) will serve as a multi-sectoral platform for coordination, research and development on innovations and monitoring of regional programs that support the advancement of TVET in the region.” (ASEAN Secretariat 2021a, 55)

It is hoped that the ATC, as a new actor at the supranational macro level – beyond the regulatory framework – will create conditions that make it easier for actors at the meso and micro levels (usually the national TVET systems) to pursue TVET with a degree of autonomy, oriented toward the needs of the labour market as well as the needs of individuals, with ambitious goals, including equity, inclusion and sustainability. The situation may be different in some nation states, but across ASEAN, TVET is still characterised by institutional and financial weaknesses. It remains relegated to partners, is conditional on support and cooperation, and has little profile of its own vis-à-vis higher education.

This often-voiced criticism can be countered, to some degree, by the progress achieved in the last decade – not only in some national TVET systems, but also in terms of a supranational regulatory framework. At the same time, caution is still advised. The newly created ATC is conducive to developing governance according to the maxims of UNESCO or the European Council and will continue to build on the framework already created. But many problems persist. There are still vast differences between and within countries. The ATC cannot take binding decisions beyond particular country interests (ASEAN Secretariat 2021c, 279) and external funding is still the rule. On a positive note, the Council confirms an awareness in ASEAN that vocational education and training need supraregional macro actors to take over what the ASEAN Secretariat can only fulfil to a limited extent.

The ATC offers considerable hope for better TVET governance in relation to transregional stakeholders, potentially leading to stronger cooperation with the private sector – beyond a diversity of perspectives and expressions of goodwill. Although their participation in shaping TVET has no legal basis (as it does in the German dual model), the Council commands respect and a reputation for assertiveness – social capital, as it is called in social science (Gessler & Siemer 2020). The ATC is the sum of its members and benefits from their “preliminary work” – at the same time, it is a new instrument that amounts to more than the sum of its parts on account of its institutional nature.

There are no grounds for pessimism. What the ASEAN education institutions have already created in terms of a regulatory framework, together with SEAMEO, external partners and other actors, suggests that there is every reason to expect that the same actors will now follow this up as an ATC in the sense of improved TVET governance. This would do much to enhance the attractiveness of vocational education and training in particular. Higher quality TVET and improved governance go hand in hand.

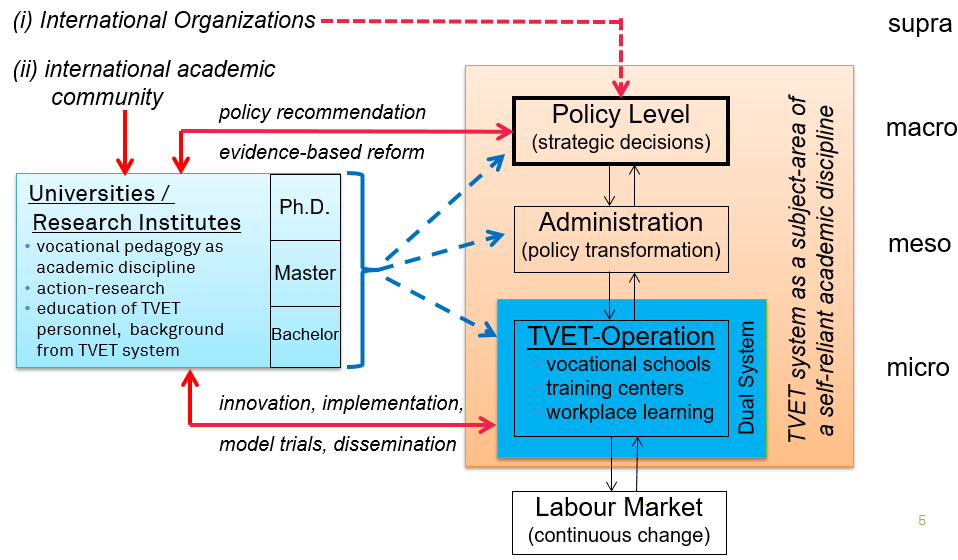

This will require the development of regional capacities in TVET research. Frommberger & Baumann (2020, 721) argue that governance itself must become the subject of research so that it can do justice to its increased relevance to the quality of TVET. Governance is, at the same time, dependent on the further development of TVET itself, for example with regard to curricula and quality standards. Expansion of regional research capacities promotes independent TVET; this benefits governance in the form of self-direction. Again, this is a matter of mutual reinforcement: regional research improves the quality of TVET, including governance, and the latter can contribute to good regional research. The following diagram distinguishes between macro, meso and micro levels, thus making the connections clearer:

The demands that the labour market places on TVET confront governance on a macro (strategic decisions), meso (policy transformation) and a micro level (TVET in schools, centres and companies). Research can provide support on all three levels: on the political level with innovative reform proposals, on the meso level by implementing reforms of aggregated actors with action research projects and model experiments, and finally on the micro level of TVET institutions by striving for excellence in TVET staff. Without autonomous regional research, the system lacks socio-cultural competence on a local level, which is an indispensable element of innovation. In other words (as shown in the diagram), relying solely on the innovating contributions of international organisations and the international scientific community, would leave TVET at the mercy of their interests, invariably compromising governance.

Independent TVET research in ASEAN is still in the process of being established, although some progress has been made. RAVTE’s journal TVET@Asia online (The Online Journal for TVET in Asia) provides a forum for the discussion of research into modern vocational education and training (digitisation, quality assurance, WBL, qualifications). Among the institutes in the region, the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET) deserves a mention, although the Republic of Korea only belongs to the ASEAN+3 formation, not to ASEAN itself. The Faculty of Technical and Vocational Education at the University of Tun Hussein Onn in Malaysia (UTHM) is also of interest, now cooperating with the University of Bremen and the TU Dortmund. A research institute established at UTHM, the Malaysian Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (MyRIVET), has been in existence for four years. In spite of this generally positive state of affairs, the resources and know-how for independent and thorough regional TVET research are often still lacking. Recognising this fundamental problem of scarce research capacity in the region, the German Federal Ministry of Science and Research (BMBF) launched the “Progressing Work-Based Learning in the TVET system in Thailand” (ProWoThai, 2019-23) project, with scientific support from the UNESCO Chair for TVET and competence development for the future of work. As a result, the Research Center for Technical and Vocational Education and Training in Thailand was established at Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna in Chiang Mai and soon attracted strong partners from the private sector and policy backgrounds. This is an impressive example of the need for action and reform-oriented TVET research.

4 Conclusion

The ASEAN region has a range of organisations and actors dedicated to improving TVET in across national boundaries – from education and training to consulting services and research. Structural and instrumental foundations have been laid at the regional level to make TVET, including its governance (national and supranational), more efficient and effective. The ASEAN TVET Council is an effective instrument as a new macro-level actor. Further expansion of regional TVET research is critical for future development.

Looking at the ASEAN-TVET panorama in its entirety – regulatory frameworks, instruments, relevant stakeholders, the ATC as an official body of ASEAN, external partners, profound approaches of independent TVET research – it seems feasible to aim for ambitious goals through governance. Nevertheless, certain hurdles cannot be ignored:

- ASEAN structures dealing with vocational education and training are inadequately equipped and overly dependent on cooperation (donors).

- The ATC as a framing macro-level actor does not have direct access to TVET quality improvement in nation states (chronic underfunding of national TVET systems, compounded by a lack of influence).

- The distinction between vocational and higher education is poorly defined. When both institutions need to be served, there is a tendency to favour universities over “downstream” vocational education.

- The current forms of vocational education in ASEAN – at universities below the bachelor level, or skills development according to the interests of the economy – are essentially Western imports. Governance in the sense of a bottom-up or participatory strategy would need to recognise the cultural conditions of the region in terms of vocational training theory and philosophy.

Profound and sustainable improvements in TVET governance across the ASEAN region require more trust in the self-organising capacities of regional actors. There are “best practice examples” to guide regional initiatives (Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand). As long ago as 2013, the so-called “Thanyaburi Statement to Support International Collaborations in Vocational and Technological Education” (2013) advocated for the introduction of a regional, clearly delineated scientific discipline of vocational education with cross-cultural validation of its insights and solutions to ensure better integration into society.

Literature

ASEAN Quality Assurance Network (2020). ASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF). Guidelines for Reviews of External Quality Assurance Agencies in ASEAN. Version 2.0. Cyberjaya: ASEAN Quality Assurance Network Secretariat.

ASEAN Secretariat (2015). ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat. Online: https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ASEAN-2025-Forging-Ahead-Together-final.pdf (retrieved 30.11.2022).

ASEAN Secretariat (2020a). ASEAN Declaration on Human Resources Development for the Changing World of Work and Its Roadmap. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat. Online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Declaration-on-Human-Resources-Development-for-the-Changing-World-of-Work-and-Its.pdf (retrieved 30.11.2022).

ASEAN Secretariat (2020c). ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework (Final Version). Referencing Guideline. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat. Online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/AQRF-Referencing-Guidelines-2020-Final.pdf (retrieved 05.12.2022).

ASEAN Secretariat (2021a). Human Resources Development (HRD) Readiness in ASEAN. Regional Report. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat. Online: https://asean.org/book/regional-study-report-on-human-resources-development-hrd-readiness-in-asean-regional-report/ (retrieved 18.12.2022).

ASEAN Secretariat (2021b). ASEAN Work Plan on Education 2021-2025. Adopted by ASED on 31 May 2021. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat.

ASEAN Secretariat (2021c). ASEAN Development Outlook: Inclusive and Sustainable Development. Jakarta: The ASEAN Secretariat. Online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ASEAN-Development-Outlook-ADO_FINAL.pdf (retrieved 18.12.2022).

ASEAN TVET Council (2020). Terms of Reference of the ASEAN TVET Council. Adopted by AEM, ALMM, ASED. Online: https://www.aseanrokfund.com/resources/terms-of-reference-of-the-asean-tvet-council (retrieved 20.12.2021).

ASEAN TVET Council (2021). Work plan of ASEAN TVET Council (2021-2030). Endorsed by ATC on 15 September 2021. Online: https://sea-vet.net/images/atc/Endorsed_by_ATC_ATC_Work_Plan_2021-2030_30_Sept_2021_clean1.pdf (retrieved 30.11.2022).

Bateman, A., Keating, J., Gillis, S., Dyson, C., Burke, G., & Coles, M. (2012). Concept Paper EAST ASIA SUMMIT Vocational Education and Training Quality Assurance Framework. Online: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/235807 (retrieved 12.12.2021).

Becker, M. & Spöttl, G. (2019a) Guidelines to Vocational Disciplines. Aligning the Regional TVET Teacher Standard for ASEAN with Relevant Economic Sectors and Occupational Fields. Bonn: GIZ.

Becker, M. & Spöttl, G. (2019b): Guidelines to Monitoring and Assessment of TVET Teacher’s Performance and Quality. Reference to the Regional TVET Teachers Standard for ASEAN. Bonn: GIZ.

Becker, M. & Spöttl, G. (2020). Regional TVET Teacher Standard for ASEAN Essential Competencies for TVET Teachers in ASEAN. Second Version (Dec. 2019). Bonn: GIZ.

Bin Bai & Paryono (eds.) (2019). Vocational Education and Training in ASEAN Member States. Current Status and Future Development. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Büchter, K., Bohlinger, S., & Tramm, T. (2013). EDITORIAL to issue 25: Order and governance of vocational education. In: bwp@ Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, Issue 25, 1-6. Online: http://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe25/editorial_25.pdf (retrieved 16.12.2013).

Cedefop (2016). Governance and financing of apprenticeship. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Online: http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/de/publications-and-resources/publications/5553 (retrieved 14.06.2016).

Chakroun, B. (2019). Work-based Learning: A Research Agenda for New Policy Challenges. In Bahl, A. & Dietzen, A. (eds.): Work-based Learning as a Pathway to Competence-based Education. A UNEVOC Network Contribution, 311-318. Bonn: BIBB.

Flatten, L., Haug, A., Huster, J., Malerius, F., Robaschik, F., & Westenberger, A. (2019). Growth market ASEAN. Opportunities in Southeast Asia. In: GTAI (Germany Trade and Invest). Bonn: GTAI.

Frommberger, D. & Baumann, F.-A. (2020). Internationalization of vocational education and training. In Arnold, R., Lipsmeier, A., & Rohs, M. (eds.): Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, 3, 713-724. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Gessler, M. & Siemer, C. (2020). Sustainability of international VET cooperation: capturing social capital through personal network analysis. In DLR Project Management Agency (ed.): Vocational Education and Training International: Sustainability, 44-47. Bonn: BMBF.

GIZ-RECOTVET (2019). Standard for In-Company Trainers in ASEAN Countries (first: February 2015). Jalan Pasar Baharu: SEAMEO VOCTECH Regional Centre. Online: https://sea-vet.net/initiatives/180-in-company-training-standard-in-asean-countries (retrieved 13.04.2021).

Hauschildt, U. & Wittig, W. (2018). Governance in vocational education and training. In Rauner, F. & Grollmann, P. (eds.): Handbook of vocational education research, 3, 271-278. Bielefeld: wbv Media.

Lay Hwee, Y. (2020). ASEAN and EU. From Donor-Recipient Relations to Partnership with a Strategic Purpose. In Koh, T. & Lay Hwee, Y. (eds.): ASEAN-EU Partnership. The Untold Story, 3-12. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

Mahbubani, K. (2017). Singapore and the ASEAN Secretariat: A Marriage Made in Heaven. In Koh, T., Seah Li-Lian, S., & Chang, L. (eds.): 50 Years of ASEAN and Singapore, 313-320. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

Rauner, F. (2009). Steuerung der beruflichen Bildung im internationalen Vergleich. In Bertelsmann Foundation (ed.): Steuerung der beruflichen Bildung im internationalen Vergleich. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation.

RAVTE (2015). Five Point Plan on TVET Improvement for AEC of 2015. Online: http://www.ravte-asia.rmutt.ac.th/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/RAVTE-5-Point-Plan.pdf (10/15/2021).

Schimank, U. (2007). The governance perspective: Analytical potential and upcoming conceptual issues. In Altrichter, H., Brüsemeister, T., & Wissinger, J. (eds.): Educational governance. Action coordination and governance in the education system, 231-260. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Schröder, T. (2017a). Theories for Practice: A Participatory Action Research Approach for the Establishment of the Regional Association for Vocational Teacher Education in Asia (RAVTE). In Pilz, M. (ed.): Vocational Education and Training in Times of Economic Crisis. Lessons from around the world, 171-187. Basel: Springer.

Schröder, T. (2017b). Development and cognition process instead of transfer. A systemic bottom-up approach to the sustainable development of a vocational education-oriented higher education association in the Southeast Asia region. In Geiben, M. (ed.): Transfer in international VET cooperation, 109-123. Bonn: BIBB.

Schröder, T. (2019a). Regional Association for Vocational and Technical Education in Asia (RAVTE): A regional structure for disseminating vocational education and training approaches and vocational education and training research as a development contribution in the ASEAN region. In Gessler, M., Fuchs, M., & Pilz, M. (eds.): Concepts and effects of the transfer of dual vocational education and training, 437-461. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Schröder, T. (2019b). A regional approach for the development of TVET systems in the light of the 4th industrial revolution: the regional association of vocational and technical education in Asia. In: International Journal of Training Research, 17, 1, 83-95.

Schröder, T. (2022). Prospects for regional vocational education and training in the ASEAN region. An overview of institutions, programs, actors and initiatives. In Grollmann, P., Frommberger, D., Deißinger, T., Lauterbach, U., Pilz, M., Schröder, T., & Spöttl, G. (eds.): Comparative vocational education and training research – results and perspectives from theory and empirics. Anniversary Edition of the International Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, 56, 224-244. Bonn: BIBB.

SEAMEO Secretariat (2020). 7 Priority Areas 2015-2035. Strategic Goal 04: Promoting Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). Bangkok: SEAMEO Secretariat.

SEAMEO Secretariat (2021). SEAMEO 55 Anniversary 1965-2020. Bangkok: SEAMEO Secretariat.

SEAMEO TED (2021). Progress Report 2020-2021. Two-year journey amidst the pandemic. Phnom Penh: SEAMEO TED.

SEAMEO VOCTECH (2021). Annual Report 2019-2020. Preparing TVET for Industry 4.0. Bandar Seri Begawan: SEAMEO VOCTECH.

Seel, F. & Komuthanon, A. (2020). Implementing the Standard for In-Company Trainers in ASEAN Countries (ASEAN In-CT Standard). Country Case Studies Thailand. Bonn: GIZ. Online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/up/20200921_ASEAN_In-CT_Standard_Implementation_Thailand_FINAL.pdf (retrieved 18.12.2022).

Stoker, G. (2018). Governance as theory: five propositions. (Reprint, original: 1998). In: International Social Science Journal, 68, 227/228, 15-24.

UNESCO (2010). Guideline for TVET Policy Review Draft. Paris: UNESCO. Online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187487 (retrieved 03.12.2022).

UNESCO (2022). Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training for successful and just transitions. UNESCO Strategy 2022-2029. Paris: UNESCO. Online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/unesco_strategy_for_tvet_2022-2029.pdf (retrieved 30.11.2022).

UNESCO-UNEVOC (2021a). TVET governance. Steering collective action. New qualifications and competencies for future-oriented TVET. Volume 1. Bonn: UNESCO-UNEVOC.

UNESCO-UNEVOC (2021b). TVET advocacy. Ensuring multi-stakeholder participation. New qualifications and competencies for future-oriented TVET. Volume 2. Bonn: UNESCO-UNEVOC.

UNESCO-UNEVOC (2021c). TVET delivery. Providing innovative solutions. New qualifications and competencies for future-oriented TVET. Volume 3. Bonn: UNESCO-UNEVOC.

Vitic, I. (2020). EU and ASEAN. World regions with a social profile. Baden-Baden: Nomos.