Abstract

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is a prime component for ensuring a country’s economic growth and sustainable development in the 21st century. The government of Bangladesh (GOB) is prioritising TVET to produce skilled human resources that address the national and global employment markets. The GOB’s strategy in the 8th Five-year plan (2021-2025) strengthens TVET as a tool for achieving sustainable development goals (SDG) by 2030, and attaining developed nation status by 2041. In acknowledging these national targets, this research focussed on the governance structure of Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Bangladesh and the challenges it faces. The contemporary trend is one of rapid expansion of TVET enrolment, without compliance with other human and non-human resources. Such expansion of enrolment can impact the effectiveness of institutional management, the quality of teaching / learning, as well as TVET products and services. The author reviewed relevant documents, journals, and contemporary publications. Existing acts, policies, and legislative guidelines were also part of the study. TVET policymakers, administrators, experts, and heads of TVET institutes were interviewed. Quality assessment tools and indicators were used to measure the performance of the TVET programme. The study identified the prevailing challenges that are emerging in all three dimensions of TVET governance: as the instrument (acts, policies, regulations, and legislatures), in operations (institutions and organisations used to translate TVET instruments), and the delivery of products and services. The findings recommend a logical reframing of TVET governance structure. This research will also be helpful for researchers, policymakers, policy formulators, experts, and practitioners of TVET for further research and development of TVET.

Keywords: TVET, governance, governance dimensions.

1 Introduction

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) is considered as a prime component for ensuring a country’s economic growth and sustainability in the era of the 21st century (Pavlova 2014). It is one of the most effective tools for producing a skilled and classifiedworkforce. (The term ‘classified workforce’ may be explained as the occupational classification of the employed and upcoming workforce, usually consistent with the ISCO (International Standard Classification of Occupation). For example, the Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) has introduced 10 levels of educational qualification that will match occupational demand within the country and the global employment market (MOE 2022). In consideration of this concept, employed graduates of the 10 levels of BNQF will be termed as the classified workforce. Similarly, graduates of the 10 levels of Australian Qualification Framework (AQF), the 10 levels of the Singapore Standard Classification of Occupation (SSCO), 8 levels of Malaysian Standard Classification of Occupation (MSCO) and EU countries Skills Competence and Occupations (ESCO) can be termed as ‘classified workforce’.)

The achievement level of the national skills standard classified workforce is one of the most important indicators for measuring the development status and global competitiveness of any country, as evidenced by the developed and rapidly developing countries around the world. Meeting the demands of a standard classified workforce is not only dependent upon the number or range of occupations and the supply of qualifications, but is directly linked to the different hierarchical skills levels as per national standards classifications of the jobs in the respective occupational fields (Rafique 2021).

Education and skill levels of the labour force are key to enhancing the overall productivity of the economy. In human resource development planning, there is a strong correlation between the proportion of TVET and per capita income; many countries in the Asia Pacific region have strengthened their policy guidance and regulatory frameworks of TVET and accelerated GDP growth, productivity, employment generation, and rapid poverty reduction (Pavlova 2014). There is a long-standing debate between general education and TVET. Which stream is more effective in promoting growth acceleration and ensuring a country’s sustainable economic development? There is no conclusive answer to this question. European education policies favoured specialised vocational education, in terms of growth rates and welfare, during the 1960s and 1970s, when technological change was relatively slow. During the information age of the 1980s and 1990s, new technologies emerged and contributed to an increased growth gap. Both general and technical education are well suited to adapt to a rapidly changing world. One main policy implication for developing countries is that a strong focus on vocational training and skills development can promote a higher growth trajectory. Hence, a mix of quality general education with vocational training is essential for sustained growth and development (Kazi 2021). Contemporary research also shows that the proportion of technical manpower is considered one of the determinants for accelerating national Gross Domestic Product (GDP). A greater proportion of technical manpower (TVET graduates) has resulted in higher GDP and experience from all developed and fast-developing countries, including OECD member countries (Rafique 1996). Malaysia demonstrated this manpower development plan in their new economic model and economic transformation programme. Their projection showed that 3.3 million new jobs would emerge by 2020. TVET would account for 1.3 million (40%) of them. The programme saw Malaysia introduce a total of 8 levels of standard Classification of Occupation (MSCO). Australia introduced 10 levels in their Qualification Framework (AQF), planning to produce 17% high-level university graduates, and 50% mid-level technical manpower, of whom 35% reach diploma level and 33% are classed as lower level skilled manpower. India planned to produce a skilled workforce of 700 million to address the world job market. In their National Education Policy 2020, they formulated a multi-approach policy guidelines to reform education and training programmes. India planned to produce 26.4 million STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics) graduates to address mid and high-level jobs in the global market. By 2030, India is forecast to address 25% of middle and high-level managerial jobs in the world (Rafique 2021).

Bangladesh is the 8th most populous country in the world. Its demographic dividend is reflected in 2.2 million of working age entering the labour market every year. Bangladesh had a population of 157 million in 2013 and will rise to 202 million by 2050, then drop to 182 million by 2100. In the hundred years from 2001 to 2100, Bangladesh will reach its highest working age population of 128 million in 2030. Population density is another significant factor in the country’s socio-economic planning. Density stands at 1178 per sq. km (2020), rising to 1402 in 2050, the highest population density in the world (Rafique 2017).

Youth unemployment is one of the major challenges to maintaining economic growth and sustainability. The youth unemployment rate is 10.6% and the share of unemployed youth in total unemployment is 79.6%. As per the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Labour Force survey–2017, 87% of the workforce are employed in the non-formal sector and only 13% in the formal sector (BBS 2017). Informal workforces generally have no formal education and no occupational training. The growth rate of the employed and upcoming workforce was 2.62% for the period 2013 to 2016 in a total workforce of 61.5 million. The growth rate and size of this employed and upcoming workforce increased to 2.75 and 70.6 million respectively in the years 2017 to 2020. This will rise to 2.85 and 81 million in the period 2021-2025, and to 3% and 94 million respectively between 2026 and 2030 (BBS 2017).

Skills development of the youth population largely depends on the effectiveness of TVET in increasing employability and job market responsiveness. The government of Bangladesh (GOB) has introduced multilevel governance and management reform initiatives with specific strategies to strengthen TVET as a tool for achieving sustainable development goals, perspectives and plans. In essence, to sustain high economic growth, reduce poverty and income inequality, the enhancement of vocational education and training should be a core theme of the ensuing 8th Five Year Plan (2021-2025). While the 7th FYP (2016-2020) laid out the foundation for developing the basic ecosystem of skills development in the country, the 8th FYP will focus on reforming the education and skills development sectors to reflect the aspiration of its citizens (GED 2020).

Strengthening TVET Governance is a priority on the agenda to enhance the quality of TVET in Bangladesh. Governance influences the formulation and implementation of policies by forming the basis on which policies are monitored, reviewed, and restructured as per the needs of the country, society, region, and system. However, despite the rapid expansion of TVET in Bangladesh, institutions and organisations capacities face challenges in maintaining the quality of training whilst keeping pace with the changing needs of the employment market. Internal efficiency faces multilevel crises which may increase over time. GOB has continued to stress the relevance of education in terms of quality, reducing inequality, and leveraging knowledge and skills in science, technology and innovation. Government is concentrating more on inclusive and quality education, quality teaching, adult literacy and lifelong learning. Future policies and programmes in the education sector will focus on sustaining past achievements and will address emerging issues that require extensive and coordinated reform in TVET governance and management capacity. From this perspective, this paper seeks to:

(a) Illustrate the present TVET governance structure in Bangladesh;

(b) Analyse the performance of TVET programmes in the current context of Bangladesh;

(c) Formulate TVET governance reform proposals to meet those national goals by improving the quality of TVET in Bangladesh.

Data and information used in this study was extracted from the author’s recent study, “Quality TVET: Opportunities, Challenges and Policy Options for Bangladesh” supported by the Directorate of Technical Education (DTE), Ministry of Education, Bangladesh.One of the main areas of the study was TVET governance structure and its further reform. In addition, the researcher has further reviewed relevant research documents, journals, publications, existing acts, policies, and contemporary legislative documents. Interviews were conducted with TVET policy formulators, administrators, experts, and managers/heads of TVET institutes.

This study comprises four main sections. The first (ongoing) provides an overview of TVET and TVET governance in Bangladesh. The second section analyses the performance of the TVET programme and presents findings of the study. Logically developed Governance reform proposals based on these findings will be described in the third section. The fourth and concluding section addresses potential implications and further research areas.

1.1 Conceptualising Education and TVET Governance

Governance is the process of decision-making by which decisions are implemented or not implemented. The World Bank defines governance as how power is practised in a country’s management of economic and social resources for development. Bernstein defines governance as the execution of economic, political, and administrative authority to manage a nation’s affairs at all levels (Bernstein 2017). Governance is how people are ruled, the affairs of the state are administered and regulated, as well as a nation’s system of politics and how this functions in public administration (Landell-Mills & Serageldin 1991). There are many definitions of education governance. One such typical and compact definition is: “Education governance is the system and standards through which organisations control their educational activities and demonstrate accountability for the continuous improvement of quality and performance”. Eminent TVET scholar Abdur Rafique defines governance as the comprehensive device of a nation that ensures transitions of the prevailing culture to the learners to live in and improve on it. Logically, education governance is contextual to the institution, community, state, and country, and even for the public, private and corporate institutions. Each institution has its own set of purposes and objectives to design and perform its functions. Education governance is always required to remain responsive to the time and to accommodate new policy goal directives and practices generated and adopted (Rafique 2014).

1.1.1 TVET Governance in Bangladesh

Educational governance system of Bangladesh is divided into different streams. There are two ministries in Bangladesh working for education as per the level of education; the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MOPME) and the Ministry of Education (MOE). Primary level education provides two major institutional arrangements; general and madrasah (Arabic for educational institution), while secondary education has three major streams: general, technical-vocational and madrasah. Higher education, likewise, has 3 streams: general (inclusive of pure and applied science, arts, business and social science), madrasah and technology education. Technology education includes agriculture, engineering, medical, textiles, leather technology and ICT. Madrasahs functional parallel to the three major stages, have similar core courses to the general stream (primary, secondary and post-secondary) but place additional emphasis on religious studies (TMED 2023). The Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED), under the Ministry of Education, operates as the sole agency for TVET governance systems in Bangladesh. TMED has the mandate to formulate acts, policy and legislative orders to ensure quality education and training as per the needs of the society and meet the challenges of the 21st-century labour market. Under the TMED, there are two major sections; one is technical and the other is madrasah (religious) education. Technical education provides three levels of education and training: short course occupational training, certificate courses and diploma level courses. As per the BTEB Act-2018, technical vocational education and training are categorised in 14 types under 6 (six) groups. These are: diplomas, certificates, basic trade courses, National Technical Vocational Qualification Framework (NTVQF) certifications, professional and in-service programmes and TVET teacher training programmes. The TMED has set a target to expand TVET from 17.18% in 2021 to 25% by 2025, 30% by 2030 and 41% by 2041 (figure 1). To achieve this, the governance structure of TVET was addressed in the Eighth Five Year Plan: 2021-2025 (GED 2020) of Bangladesh, identifying institutional and organisational capacity enhancement issues.

1.2 Effective and Good Governance

Effective governance is often referred to as ‘good governance’ – the process whereby public institutions conduct public affairs and manage public resources that promote the rule of law and the realisation of human rights (civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights). Effective or good governance encompasses participation, the act of law, transparency, responsiveness, consensus, equity, inclusiveness, effectiveness, efficiency, accountability, etc. Eight characteristics considered good governance are shown in figure 2. Effective TVET requires a reframing of good governance. Bangladesh must address effective governance to achieve the visionary target of TVET.

1.1 Governance Dimensions and Framework

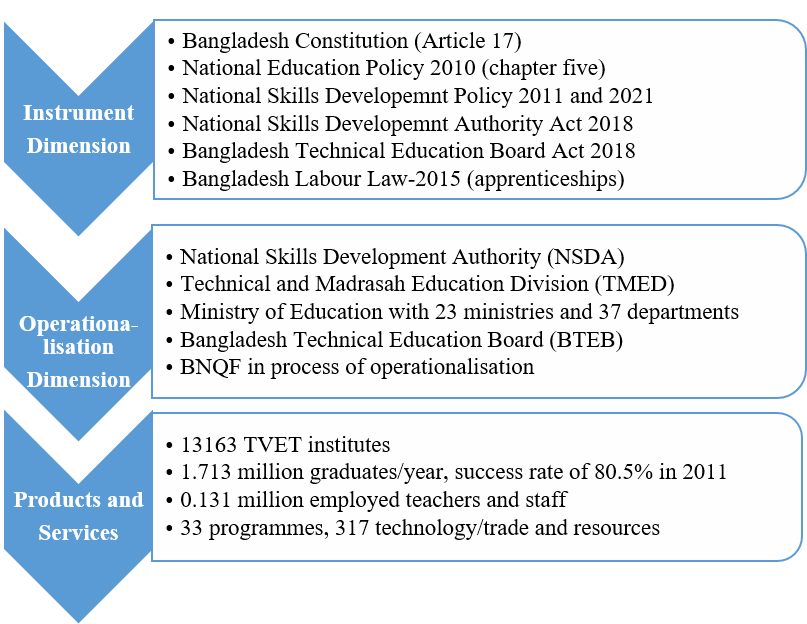

The education and training programme needs 21st century skills integration based on properly formulated applications of the three governance dimensions:

- Instruments, including acts, mandates and policies;

- Operational translation of instruments (acts and mandates) through all human and non-human inputs, teachers qualification frameworks, organisations and institutions;

- Delivery of product and services: outputs/outcomes such as graduates for employment or further education, well-trained teachers, researchers, research findings, innovations and policies for further review and improvement of governance dimensions, components, and performance. Further to these products and services, a positive contribution to social and cultural enhancement (Rafique 2021)

Figure 3 illustrates governance dimensions and the corresponding structural framework.

2 Analysis and Findings

2.1 Analysis of TVET Governance in Bangladesh

TVET governance in Bangladesh comprises three dimensions; instruments, operations, and products and services. The instrument dimension is based on article 17 of the Bangladesh constitution. National Education Policy, National Skills Development Policy, National Skills Development Authority Act, Bangladesh Technical Education Board Act and Bangladesh Labour Law (apprenticeships) have been developed under this constitution. Different institutions and organisations are working to operationalise the instruments with the National Skills Development Authority (NSDA), Ministry of Education, Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED) alongside 23 ministries and 37 departments. Among all the TVET agencies and organisations, the Ministry of Education (MOE) is the largest provider of TVET. The third dimension of governance relates to the products and services of TVET. As noted, there are three types of TVET programme in Bangladesh according to the level of education or training attained. These are: the Diploma level programme, certificate programme, and the (trade / short) Competency Based Training & Assessment (CBT&A) programme. There are 13,163 TVET institutions, producing around 1.7 million TVET graduates every year with the engagement of 0.13 million TVET teachers and staff – 0.074 million teachers and 0.054 million staff (BBS 2016). The governance structure of TVET in Bangladesh is shown in figure 4.

The Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) has recently been approved by the Ministry of Education (MOE 2022). The BNQF comprises 10 levels. The first 6 levels are under the mandate of TVET and the rest (7-10) are under the mandate of the University Grant Commission (UGC). At present, the BTEB is implementing 6 levels in the National Technical Vocational Qualification Framework (NTVQF). Through operationalisation of BNQF, the NTVQF will be merged with the first 6 levels of BNQF.

2.2 Instrument dimension

2.2.1 Analysis of Education Act in Bangladesh

TVET-related constitutional mandates, acts and other legal instruments have been reviewed in the instrument dimension in order to meet national TVET targets set by the Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED), Ministry of Education. The fundamental principles of state policies are described in article 17 of the Bangladesh Constitution. The state shall adopt effective measures for establishing a uniform, mass-oriented and universal education system and extend free and compulsory education to all children to the stage as may be determined by law. Further, the state shall relate education to the needs of society and produce properly trained and motivated citizens to serve those needs and eradicate illiteracy within such time as may be determined by law (GOB 1972, Article 17). Within this constitutional provision, Bangladesh has established eight education commissions/committees since 1974. In 2013, according to national education policy guidelines, a Right to Education Act (REA) was drafted but has yet to be ratified (see Table 1, finding 1). Bangladesh is one of the few countries in the world without an enforceable right to education for all citizens. In 2009, India approved its own REA and enlisted as one of the 135 countries in the world to have done so (Rafique 2014). In such an absence of an act/regulatory provision, the government of Bangladesh is responsible for ensuring education. But, education is not an established right of the citizen. The TVET and skills development programme is regulated through the Bangladesh Technical Education Board Act-2018, National Skills Development Authority (NDSA) Act-2018. Regulatory provision under the BTEB Act is as follows: a framework for curricula development of TVET courses, assessing and certifying of students/trainees, affiliating/accrediting TVET institutes/centres, assessment of teachers/trainers and assessors certification, making operational regulations for prescribing student-teacher ratios, occupational frameworks for NTVQF (newly approved BNQF from levels 1 to 6) etc. The crucial question is: can NSDA and BTEB transform the huge existing and future workforce into a skilled and classified workforce to guarantee global competitiveness and achieve sustainable development goals? NSDA analysis and review indicate that, as per the projection of a least dependent Bangladesh workforce by 2030, Bangladesh lacks a comprehensive development plan to achieve SDG by 2030 (see Table 1, finding 2). The statistical findings of the instrument dimension are shown in Table 1.

2.2.2 Analysis of Education Policy in Bangladesh

The present National Education Policy-2010 (NEP-2010) is the 8th since Bangladesh became independent in 1971. A new education policy or committee report is developed by the parliament almost every five years. Most of the issues addressed remain unimplemented. The NEP-2010 recommended eight years of compulsory primary education (instead of 5 years), yet this remains unaddressed in 2022 (MOE 2010). Researchers have raised serious concerns, suggesting that it is difficult to execute within the present structure without infrastructural development or the recruitment of qualified teachers. In a 2010 review on education policy, Abdur Rafique, a prominent researcher of Bangladesh, stated that, “Reforming primary education into eight years duration is neither feasible nor possible (see Table 1, finding 3) in the current form of the education system in Bangladesh” (Rafique 2021). The analysis and findings are shown in Table 1.

2.2.3 Analysis of TVET Acts and Policies in Bangladesh

A National Skills Development Policy (NSDP-2011) was approved in January 2012 with the aim of upgrading Bangladesh as a middle-income country through TVET and skills development by 2021 (MOE 2011). The policy emerged as a comprehensive strategy for guiding skills development in Bangladesh, leading to the establishment of the National Skills Development Council Secretariat (NSDCS). Competency Based Training and Assessment (CBT&A) under the National Technical Vocational Qualification Framework (NTVQF) was allied to the Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) and Bureau of Manpower Employment and Training (BMET). Under this qualification framework, 13 Industry Skills Councils (ISC), 190 occupations, and 415 competency standards have been developed. About 0.1 million students have been certified by 450 registered training organisations (DTE 2021).

The NSDP 2011 should have been reviewed after 5 years, but this did not happen. However, under the provision of the National Skills Development Authority Act-2018, the National Skills Development Authority (NSDA) introduced the new National Skills Development Policy-2021, parallel to the existing NSDP-2011 (see Table 1, finding 4). Initially, the governing board of NSDA approved the new policy, but final approval will come from the cabinet. As a result, TVET and Skills development programmes are governed through two streams: Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED) under the Ministry of Education (MOE) will govern TVET (excluding CBT&A and skills training) and related departments. The Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) will provide accreditation, quality assurance, and certification services to TVET providers. Another stream will be governed by the NSDA with other departments/organisations/industry associations to implement skills development and training programmes (excluding formal TVET).

There seems to be a degree of overlap in the functions and mandates of these two skills policies (NSDP-2011 and NSDP-2021) and authorities (NSDA and BTEB). This could interrupt programme implementations (see Table 1, finding 4). Researchers are concerned about the overlapping issues among acts and policies of TVET in Bangladesh:

“The NSDA Act, BTEB Act, and the NFE Act have some issues to be further clarified in line with the mandates and capacity of the respective authority; roles of the apex body (NSDA) needs strengthening for coordination among TVET and skills providers (Khan 2019). If the NSDA becomes the implementing authority, who will coordinate the TVET and skills development programmes provided by 23 ministries and more than 37 departments? The key findings are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Findings on Instrument Dimension

| Instrument | Data Source | Finding(s) |

| 1. Bangladesh Constitution 2. National Education Policy 2010 3. NSDP-2011 4. NSDP-2021 (proposed) 5. NSDA Act-2018 6. BTEB Act-2018 | (a) Article 17-a, b & c (Fundamental right) (b) 17.b is relevant to TVET (c) NEP-2010, chapter -3 and 5 (d) NSDP-2011 (e) NSDP-2021 (f) NSDA Act-2018 (g) VTEB Act-2018 | 1. The draft of the Right to Education Act (REA) was developed in 2013 but is not yet approved 2. Bangladesh does not have a workforce development plan to harness its human potential as the 8th largest country as per the size of its workforce 3. Reform of 8 years of primary education is neither feasible nor possible within the existing framework of primary education. Requires needs further study 4. Introducing NSDP-2021 parallel to existing NSDP-2011 may disrupt programme implementation due to overlapping mandates of NSDA and BTEB |

2.3 Operationalization Dimension

The Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED) under the Ministry of Education has the mandate to formulate TVET-relevant acts, laws, rules/regulations and operationalise these instruments through different institutions/organisations. These can then be translated into plans, programmes, projects, and frameworks. TMED is also responsible for meeting the national targets set by the government, based on its ideological, socio-political, and economic perspectives. The Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) is the national accreditation body responsible for setting the standard, quality, affiliation, examination, and certification of the TVET programme and institutes. This chapter analyses and describes the operationalisation of the instrument dimension and its performance.

TMED has prepared an integrated development action plan (2016-2030) (see Table 2, finding 5) to reach 20% TVET enrolment by 2020 and 30% by 2030 (TMED 2018). The aim is to improve the quality of TVET in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the government and included in the 8th Five Year Plan (2021-2025). This action plan developed 99 activities on different aspects of TVET. It included an initiative to establish a TVET University (see Table 2, finding 9) as per the guideline of National Education Policy-2010, the establishment of the independent teacher recruitment commission (see Table 2, finding 10) (chapter 1.7) and the development and implementation of the Teachers Qualification Framework (see Table 2, finding 11) (chapter 1.26). Both are vital to ensure the quality and timely recruitment of teachers. It will further expedite the operation of the National Education Policy guideline to meet standard student-teacher ratios (STR), quality teacher recruitment, minimise teachers’ crises, and capacity development of teachers as per the NEP-2010, chapter 5.7, 5.11, 5.17, and 5.25. Through the review of the progress report, both TMED and DTE, these issues are still unaddressed in ongoing programmes and projects.

Introducing the Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) (see Table 2, finding 6) is a milestone of progress in operationalising constitutional mandates. The state shall relate education to the needs of society and produce properly trained and motivated citizens to serve those needs. This qualification framework seeks to harmonise general education, technical-vocational education, and higher education into a quality assured system. As per the TMED report, the BNQF was approved by the steering committee but needs further acts and regulations for its operationalisation (see Table 2, finding 7). The Apprenticeship Act-1962 is in need of an update and modification (MOE 2010, Chapter 5.9). But the apprenticeship act has not been revised nor executed for industry and TVET. The Bangladesh Labour Regulation of 2015 has been approved and, in chapter 17, clause 328-349, apprenticeship has been introduced but is not operational (see Table 2, finding 8) (Bangladesh Gazette 2015). Researchers have recommended the introduction of a separate workers’ employment act for the proper operationalisation of industry-institute collaboration. The first progress report of SDG notes that the Government of Bangladesh is committed to improving the quality of TVET through operationalisation of competency-based skills qualifications and a system of recognition in the TVET sector (GED 2018). The main findings based on the above analysis of the operationalisation of TVET governance are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Findings on Operationalisation Dimension

| Instrument Operationalisation | Data Source | Findings |

| 1. TMED, TVET Integrated Action Plan 2. Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) 3. Bangladesh Labour Regulation 2015 | 1. Integrated TVET Action Plan (section 1-5) 2. BNQF Level 1 to 6 3. Apprenticeship Act-1962 And Bangladesh Labour Regulation-2015 (Chapter-17, Clause-328-349) 4. National Education Policy-2010, Chapter-5 and 28 5. BTEB Act-2018 Chapter -6 (Duty of the Board and Chapter-21) | 5. TVET Integrated Action Plan has been prepared and approved by TMED to achieve national TVET targets, but is not operational in all relevant institutions and organisations 6. Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) has been approved by the steering committee but is not yet operational 7. BNQF needs further acts and regulations to be implemented properly 8. Apprenticeship is included as a chapter (Chapter 17) under Bangladesh Labour Law 2015, but is not yet in operation 9. TVET university has yet to be established as per the guidelines of NEP-2010 10. Teachers recruitment commission has not yet been initiated 11. Teachers Qualification Framework (TQF) not yet introduced as per the mandate of BTEB |

2.4 Analysis and findings on Products and Services Dimension of TVET

TVET products and services include TVET graduates, teachers, staff, researchers, curriculum, research findings, employment, etc. Broadly, products and services are categorised as living and non-living. All human products (graduates and teachers) are living beings, and non-human products are curricula, learning materials, research documents, etc. Further, these products and services contribute to social and tangible enhancements, along with other cultural aspects which are also considered as services of TVET to society. The training institutes mainly produce and distribute products and services. In Bangladesh, 23 ministries and 37 departments provide training through 13163 TVET institutes (BBS 2016). Among these training providers, the Directorate of Technical Education is the leading department providing education and training through 200 TVET institutes (as of October 2022). The Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) is the national statutory accreditation body that determines quality and standards with reference to developing curricula, evaluating programmes, and accrediting institutions.

In this study, TVET programmes and performance were measured with five selected quality indicators: student-teacher ratio (STR), availability of quality teachers, teacher selection criteria, teacher recruitment process, and employment rate of TVET graduates. The study found that TVET institutes are running with a high STR range from 36:1 to 92:1 (national STR for TVET is 12:1), acute shortage of teachers in TVET institutes (18% teachers working and 82% of teaching posts are vacant), complex and lengthy bureaucratic processes are prevailing in teacher recruitment, a teacher crisis is increasing, teacher selection is based only on academic qualifications (no teaching skills test), poor quality and lower capacity of teachers, ineffective role of teacher training institutes (two specialised teacher training institutes are virtually non-functioning for a long time) and low graduate employment rate,(39%), poor entrepreneurship development (11%), ineffectiveness of apprenticeship act, poor and informal collaborative links between institutes and industry. These performances are shown in figure 5 to highlight the quality of products and services of TVET in Bangladesh.

2.5 Summary

In this section, all findings from three-dimensional analyses in the previous chapters are organised with a matrix in order to formulate the logical recommendations and identify the intervention areas for better output of the study. In the left-hand column of the matrix, all findings were mentioned as per the analyses. The second column is split to distribute all findings in to three governance dimensions and the last column represents the logical formulation of intervention areas.

3 Reframing TVET Governance

Analysis of the study revealed 18 major findings we can logically classify according to the three intervention areas of governance dimensions. Out of these 18 findings, 4 pertain to instrument dimensions, 7 to operationalisation and 7 relate to product and service dimensions. It is understandable that the Bangladesh TVET system is facing daunting challenges in all dimensions. A holistic approach is required covering all governance dimensions to overcome these challenges. We define this as reframed TVET governance. In this section, reframed TVET governance with the respective intervention areas will be illustrated in table 3.

Table 3: Transforming Findings into Recommendations with Intervention Areas for Reframed TVET Governance in Bangladesh

| Governance Dimension | Findings | Recommendation(s) | Agency /Ministry/ Department |

| Instrument (Act/Policy/ Regulation) | 1. The Right to Education Act (REA) was drafted in 2013 but is not yet approved | 1. Ministry of Education (MOE) must formulate the Right to Education Act (REA) for final approval by the Bangladesh parliament to ensure the fundamental and constitutional rights of citizens. | MOE/MOLJ |

| 2. Bangladesh does not have a workforce development plan to harness its human potential as the 8th largest country as per the size of workforce | 2. Bangladesh should prepare a strategic workforce plan to transform existing and future workforce into skilled workers, classified as per the BNQF | NSDA, MOE, MOEWOE | |

| 3. Reform of 8 years primary education is neither feasible nor possible within the existing frame of primary education. Further study needed. | 3. Thorough review of NEP-2010 is needed. Action plan required to ensure proper implementation | MOE | |

| 4. Introducing NSDP-2021 parallel to existing NSDP-2011 may disrupt programme implementation due to overlapping mandates of NSDA and BTEB | 4.1 TVET and Skills Development programme should devise a common skills policy and update the National Skills Development Policy-201 4.2. Overlapping of functions and mandates between NSDA Act-2018 and BTEB Act-2018 should be identified, addressed and resolved. | NSDA, MOE, BTEB and BMET | |

| Operationalisation of instrument through strengthening of institute and organisations | 5. The TVET Integrated Action Plan has been approved by TMED to achieve national TVET targets, but has not been implemented throughout all institutions and organisations | 5.1 TMED needs to develop a TVET sub-sector action plan and update existing integrated TVET development plan-2018 to meet the national target of 25% TVET enrolment by 2025 and 41% by 2041 5.2 Need to prepare a SWAP for TVET sub-sector following a detailed work plan with intervention areas identified for each area of work | TMED, DTE, BTEB |

| 6. The Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF) has been approved by the steering committee but not implemented. | 6. Need to declare BNQF through proper government order and regulatory status | MOE | |

| 7. BNQF needs further acts and regulations to be fully operational | 7. Need to review and align BNQF with job market on an occupational level. New legislation and regulatory orders etc. necessary | MOE with respective ministry and departments | |

| 8. Apprenticeship is included in Bangladesh Labour Law 2015 (Chapter 17), but is not yet in operation | 8.1 Need to operationalise respective employers industries and institutes through governmental order 8.2 Need to introduce a separate workers employment act with specific roles for employers | MOLE | |

| 9. TVET university not yet established as per the guidelines of NEP-2010 | 9. University Grant Commission (UGC) should take initiative to establish TVET University as per NEP-2010 guidelines | UGC | |

| 10.Teachers recruitment commission (TRC) has yet to be initiated | 10. There is a need to establish an independent teachers recruitment commission and Teachers Qualification Framework | MOE/TMED | |

| 11. Teachers Qualification Framework (TQF) not yet introduced as per the mandate of BTEB | 11. BTEB needs to enhance its capacity as a statutory accreditation body to operationalise a quality TVET programme and develop TQF framework | BTEB | |

| Delivery of TVET Product and Services (Graduates and Employers) | 12. High STR (36:1 to 92:1) in formal TVET institutes | 12. BTEB must set standard student-teacher ratio (STR) as per NEP-2010 guidelines | BTEB and DTE |

| 13. Acute shortage of qualified teachers is becoming more pronounced as new institutes are opening without adequate recruitment | 13.1. Based on the standard STR, a total projection of teachers’ requirements needs to be prepared with regard to TVET enrolment. As a national priority, it requires professional expertise. 13.2. Recruitment processes must be in place before any new TVET institute is opened. | TMED and BTEB | |

| 14. Lengthy and deficient teacher recruitment process | 14. A separate teacher recruitment commission should be establish as per National Education Policy-2010 guidelines with an integrated TVET plan approved by TMED. | MOE | |

| 15. Flawed teacher recruitment criteria, mostly based on academic qualifications | 15. As per the Teachers Qualification Framework (TQF), recruitment criteria should be set for TVET teachers | BTEB | |

| 16. Limited scope of professional development of TVET teachers | 16. A continuous professional development framework should be introduced for TVET Teachers and a training programme developed as per the framework | BTEB | |

| 17. Declining employment rate among formal TVET graduates (39%) | 17. An entrepreneurship programme should be promoted through the Business Incubation Centre (BIC), Technology Incubation Centre (TIC) within the framework of the Industry Skills Counsel (ISC) | TMED, DTE | |

| 18. Poor collaboration between industry and academia | 18. Industry-academia collaboration should be regulated as per the proposed workers employment act | MOI, MOLE |

4 Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight implications and recommendations which policymakers, administrators, researchers, and practitioners may adopt for further research in this arena. The strategy of the Bangladesh government as declared in the 8th Five-year plan should draw serious attention to the improvement of TVET. Existing TVET governance is experiencing a decline. This must be addressed and reframed to meet and ensure quality improvement. Bangladesh has enormous human potential (especially its youth) as the 8th largest working-age population. It currently maintains the highest population growth rate and density in the Asia Pacific Region, as well as in the whole world. Skills shortage and gaps in all sectors of the economy present serious challenges that could lead to the opportunities of the demographic dividend being squandered. Unemployed and unskilled youth will find access to the job market more difficult, potentially increasing social unrest and creating an economically unviable situation. TVET has an enormous role to play in transforming this huge human potential into a treasure for the nation, for Asia, and global society. High quality TVET can make a significant contribution to the production of a skilled workforce, accelerating sustainable economic growth, achieving SDG and other goals. The emerging nation of Bangladesh can become a skilled and developed Bangladesh.

References

Aziz, S. A. & Hoque, R. (2022). Quality TVET: Opportunities Challenges and Policy Options for Bangladesh. Dhaka: Directorate of Technical Education.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2016). Technical and vocational education and Training: Institution Census 2015. Dhaka: Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2017). Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Gazette. (2015). Bangladesh Labour Rules, 2015. SRO No. 291-Act/2015. Dhaka: Ministry of Labor & Employment.

Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB). (2018). Bangaldesh Technical Education Board Act, 2018. Dhaka: Technical and Madrasah Education Division.

Bernstein, S. (2017). The United Nations and the governance of Sustainable Development Goals. In Kanie, N. & Biermann, F. (eds.): Governing through Goals. Cambridge: MIT Press, 213-239.

Directorate of Technical Education (DTE). (2021). Annual report 2020-21. Dhaka: Directorate of Technical Education.

General Economic Division. (2017). Education Sector Strategy and Actions for Implementation of the Seven Five Year Plan (FY 2016-2020). Dhaka: Bangladesh Planning Commission.

General Economics Division (GED). (2018). Sustainable Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2018. Dhaka: Bangladesh Planning Commission.

General Economics Division (GED). (2020). 8th Five Year Plan (July 2020-June 2025). Dhaka: Bangladesh Planning Commission.

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (GOB). (1972). The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (ACT NO. OF 1972). Dhaka: Legislative and Parliamentary Affairs Division.

Kazi, I. (2021). Study 11: Managing the Skill Gap through Better Education, TVET and Training Strategies. In: Education, Health, Poverty and Social Inclusiveness: 8th Five Year Plan Background Papers, 4, 1–68. Online: Background-Studies-of-8FYP-Volume-4.pdf (gedkp.gov.bd) (retrieved 15.12.2022).

Khan, M. A. (2019). Situation Analysis of Bangladesh TVET Sector: A background work for a TVET SWAP. Online: MergedFile (oit.org) (retrieved 04.01.2023).

Landell-Mills, P. & Serageldin, I. (1991). Governance and the External Factor. In: The World Bank Economic Review, 5, 1, 303-320. Online: Governance and the External Factor | The World Bank Economic Review | Oxford Academic (oup.com) (retrieved 11.01.2023).

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2010). National Education Policy 2010. Dhaka: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2011). National Skills Development Policy – 2011. Dhaka: Ministry of Education (MOE).

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2022). Bangladesh National Qualifications Framework (BNQF). Dhaka: Ministry of Education.

National Skills Development Authority (NSDA). (2018). National Skills Development Authority (NSDA) Act 2018. Dhaka: Prime Minister’s Office.

National Skills Development Authority (NSDA). (2020). National Skills Development Authority (NSDA) 2020, Draft. Dhaka: Prime Minister’s Office.

Pavlova, M. (2014). TVET as an important factor in country’s economic development. In: SpringerPlus, 3, 1, 1-2. Online: TVET as an important factor in country’s economic development | SpringerPlus | Full Text (springeropen.com) (retrieved 05.01.2023).

Rafique, A. (1996). The Challenge of TVET for Human Resource Development: Policy Planning Strategy. Dhaka: Bangladesh Technical Education Board Press.

Rafique, A. (2014). TVET Governance Structure Reframed for Ensuring Students Learning. Mohammadpur: College Gate Binding & Printing.

Rafique, A. (2017). Build Skill Bangladesh for Emerging Bangladesh as Developed Nation. Dhaka: Institution of Diploma Engineers, Bangladesh (IDEB).

Rafique, A. (2021). The Emerging Nation, Unveiling the Treasure. Dhaka: Centre for Occupational Research and Education (CORE).

Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED). (2018). Integrated TVET Development Action Plan. Dhaka: Technical and Madrasah Education Division.

Technical and Madrasah Education Division (TMED). (2023). Technical and Madrasah Education Division. Online: www.tmed.gov.bd (retrieved 05.01.2023).