Abstract

During the worldwide disruption caused by the pandemic, policymakers and experts expressed ongoing concerns about ICT integration embedded into effective instruction. Most of the 11 SEAMEO member countries are developing countries with limited capacities in ICT application. This issue deserves greater attention, consideration and alignment. This study aims to assess ICT skills competency levels of technical education teachers. In response to this research objective, 5,704 technical education teachers from vocational-technical high schools in the 11 SEAMEO member countries were polled via a Google Forms questionnaire. The cross-sectional survey design utilised descriptive statistics and Harman’s single factor test to analyse data. An independent sample t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to test hypotheses. The results found that technical education teachers are moderately proficient in Microsoft Excel but have good internet skills. The study points to the limitations of ICT skills and confirms the ongoing need for combined resources such as ICT infrastructure, outsourcing, and curriculum review.

Keywords: Information and communication technology, technical education teacher, Microsoft Excel skills, internet skills.

1 Introduction

Technical education, through academic and vocational studies, prepares students and learners for immediate jobs by applying basic concepts of science and technology. A school-to-work approach is gaining momentum everywhere to tackle an ever-changing labour market which is strongly influenced by the digital revolution. It is typically offered in a wide variety of academic institutions including vocational-technical high schools. Technical education is flexible to capture learners’ interests and meets labour market needs with a variety of trades such as agriculture, sciences and technology, construction, and manufacturing (ADB 2009).

1.1 Preamble

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills support effective instructional skills by catering to various learning approaches, such as collaborative and inquiry-based learning. ICT reaches unlimited potentials of students and teachers (Hakkarainen et al. 2001), playing an integral part in supporting ASEAN economic integration and community building (ASEAN Secretariat 2015). ICT impacts learning societies, providing greater access to a variety of learners to build inclusive and robust learning environments (Park & Kim 2020). The computer has irreversibly changed traditional schooling with its ability to retrieve information and reach its potential as an effective tool for instructional services (Abbott 2001). The ICT competency framework for teachers informs stakeholders such as teacher training personnel, policymakers, curriculum developers, and other supporting administrators to integrate ICT in education (UNESCO 2018). Therefore, ICT skills integration and application in technical education can enhance teachers’ effective teaching methods by impacting students’ learning outcomes.

ICT comprises all technologies and services relating to computing, telecommunication provision, data management and the internet (Brown 2020). ICT means the use and application of computers, electronic instruments, data, computer networks and others including hardware and software (UNESCO 2018). In addition, ICT refers to accessibility to information through computers, the internet, cellular phones and other means of communication for societal needs (Ratheeswari 2018). ICT might be considered as an effective instrument for educational reform, departing from traditional teaching approaches (Fu 2013). Therefore, the main pillar of ICT competency framework for teachers is their ability to use a variety of digital teaching instruments and resources (UNESCO 2018).

Technical education refers to formal education delivering vocational courses at secondary education level, particularly in vocational-technical high schools, across a variety of trades. These include mechanics, electronics, electricity, agronomy, animal husbandry, food processing, tourism, ICT, etc. The main purpose of vocational-technical high schools is to equip youth with industrial skills for immediate employment (Joo 2018). Technical education teachers are instructors who teach and major any typical trades such as mechanics or construction at vocational-technical high schools. Technical education teachers play active roles in imparting relevant industrial skills to students (Samuel & Touitou-Tina 2016).

1.2 Research Problem

Teacher quality significantly impacts students’ learning outcomes (Park & Kim 2020). The competency levels of technical education teachers are key elements to ensure education and training quality (ADB 2009). However, there are a limited number of qualified teachers with the ability to teach technical education courses. Poor countries tend to lack rigorous support systems such as ICT skills provision, motivation, coaching and mentoring (Lee 2020). ICT integration into education practices has not been fulfilled because teachers have no opportunity to learn and apply these skills (Ilomäki & Lakkala 2018). Teachers are not proficient in ICT skills, hindering instructional effectiveness to maximise potential (Voelker 2021). Most of the ASEAN member countries encounter skills mismatches and shortages between supply and demand constraints to economic development due to teachers’ limited capacities (ADB 2009). Therefore, it is necessary to equip teacher training programmes with potential qualifications to guide the young generation to become an ICT-based knowledge society (UNESCO 2018).

Industry 4.0 skills disrupt traditional systems everywhere by automatising and robotising human roles to make life more convenient. To support these skills, ICT plays an integral part in communicating and coding data which result in mass production in manufacturing. In addition, technical knowledge transforms the way we work and the way we live. To this end, technical education teachers need to possess technical knowledge to assist instruction and student learning. However, ICT as part of technological knowledge is not widespread enough in teacher knowledge in the ASEAN region – only 39% of people in the ASEAN region learn ICT skills (Voelker 2021). Technical education teachers leave school with a grounding in academic theory after graduating, without having developed necessary skills like ICT (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 2015). The number of high school teachers who possess ICT skills is limited (Hakkarainen et al. 2001). Few teachers integrate ICT skills into their instruction either through remote teaching software, e-learning systems or Microsoft Excel (Voelker 2021). Technical education teachers’ ICT skills need to be considered to enhance students’ learning outcomes.

1.3 Research Significance

A competent teacher is a key factor in instilling students’ cognitive skills (Hanushek & Woessmann 2011; Lee 2020). Teachers possessing ICT skills contribute to students’ holistic growth as a self-paced learning approach with the support of ICT skills (Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz 2018). ICT integration and implementation in education are progressing gradually at schools in the 11 SEAMEO member countries (The HEAD Foundation 2017). The findings from these studies will provide insights for teachers to engage in self-assessment regarding specific skills or possible actions. Teachers will be alerted to using internet-assisted approaches, transitioning from a teacher-centered to a self-directed learning approach (Fu 2013). Support systems such as training programmes, mentoring programmes, motivation, or ICT infrastructure installations are the solution. Teachers’ ICT competencies facilitate students’ high-level thinking skills and creativity (UNESCO 2018). Policymakers are guided functionally on what skills/tasks should be emphasised. The government will be informed and knowledgeable about the ICT equipment and support needed. Budgets to maintain these should be planned and allocated. Curriculum developers will focus accurately on what has been found and communities will be aware of the nature of support which should be provided to help improve teachers’ capacities.

1.4 Research Objectives and Questions

ICT is assistive technology, supporting learning and teaching processes through technological disruption. Enhancing teachers’ ICT skills accelerate students’ learning outcome rates. ICT is a key driver in supporting the use of allocated resources effectively to achieve planned goals (Tjoa & Tjoa 2016). Embedded in vocational education and training courses, ICT can be used to aid artificial intelligence (AI) in mass production (Becker, Spöttl, & Windelband 2022). Teachers’ professional development programmes are a crucial factor in making teachers competent and effective. This research study aims to assess the ICT skills competency levels for technical education teachers from the 11 SEAMEO member countries. The two research questions are as follows:

Research question 1: What are the ICT skills deficiencies of technical education teachers?

Research question 2: What are the ICT skills proficiencies of technical education teachers?

There are three hypotheses for testing:

Hypothesis 1: There are different competency levels of ICT skills between technical education teachers based on gender (male and female).

Hypothesis 2: There are different competency levels of ICT skills among the 11 SEAMEO member countries.

Hypothesis 3: There are different competency levels of ICT skills between the older and younger cohorts in terms of years of work experience.

2 Literature Review on Technical Education Teachers’ ICT Competencies

ICT revolutionises the way we live, the way we work, and the way we communicate globally (Habaradas & Mia 2020). ICT solves almost everything we do and addresses challenges faced by people wanting to work more conveniently. The different competency levels among the 11 SEAMEO member countries in terms of ICT skills are due to their different socio-economic levels. A large number of research studies have been conducted to highlight ICT skills mastery of technical education teachers in the region.

2.1 Technical Education Teachers’ ICT Skills

The ICT competency framework for teachers embraces three levels of skills mastery: knowledge acquisition, knowledge deepening and knowledge creation (UNESCO 2018). Singapore is in the knowledge creation stage, having its own ICT ecosystem that accommodates most of the world-class technology companies that reflect the advancement of ICT skill competencies (Habaradas & Mia 2020). Mundia (2020), investigating the level of technological competence of 109 teachers in Brunei Darussalam, suggested more improvement and effort could be invested in upgrading teachers’ technological skills. Moreover, Timorese teachers are deficient in ICT skills, hindering effective teaching practices (Lopes et al. 2017). The ASEAN ICT master plan 2020 focuses on building ASEAN’s ICT capacities to reach the regional cyber ecosystem.

A quantitative study of 329 Malaysian technical education teachers to ascertain ICT skills levels in Malaysian teachers found that these teachers possessed a moderate level of ICT skills (Alazam, Bakar, & Asmiran 2012). Another quantitative study explored teachers’ ICT skill levels for integration into their instruction and highlighted a mastery level of ICT skills (Samuel & Zaitun 2007). However, some teachers possess limited ICT skills, hindering their effective instructional skills, even though they have their individual computers (Elstad & Christophersen 2017; Hatlevik et al. 2013). Internet coverage within schools in Thailand is strong, but Thai teachers’ ICT skills are limited as they have yet to adapt to the new situation (Akarawang, Kidrakran, & Nuangchalerm 2015). In addition, a quantitative study in Lao PDR exploring teachers’ ICT proficiency levels, based on 200 Laos teachers, found that their ICT capacities needed further improvement in terms of installing ICT equipment in the classroom, and developing curriculum and training programmes (Thephavongsa & Liu 2018).

2.2 ICT Skills Integration into Instructional Practices

Technological advancements imply major changes in technical education, transitioning from a traditional face-to-face model to a blended mode, impacting productivity and manufacturing (Park & Kim 2020). A quantitative study conducted by Elstad and Christophersen (2017) in Norway on secondary school teachers found that teachers effectively integrated ICT skills into their instructional activities. This qualitative research study shows that teachers can integrate ICT skills into teaching practices as a blended learning approach (Røkenes & Krumsvik 2014). A quantitative research study of 135 Cambodian teachers explored teachers’ attitudes towards ICT integration and found that teachers can integrate the use of ICT into the teaching processes with a high degree of mastery (Hun, Shimizu, & Kao 2020). Htun (2019) examined ICT development in 63 organisations including the private and public sector in Myanmar and found that ICT skills in education were underused and underdeveloped. There are different perspectives related to ICT application in reference to the socio-economic development status of each country.

Another quantitative study from the Philippines in 2015 explored the level of ICT education integration of 383 teachers and showed that ICT integration levels were limited in terms of ICT capacities and ICT tool accessibility (Marcial & Rama 2015). Hue and Ab Jalil (2013) identified ICT integration possibilities for the classroom with 109 Vietnamese teachers, finding that ICT integration was not fully being conducted within the classroom. ICT was seldom used. Lubis et al. (2011), investigating ICT integration into instruction in Brunei Darussalam, noted that teachers’ ICT skill deficiencies presented a barrier to ICT integration. Finally, Chen, Tan, and Lim (2012) used a qualitative study of two Singaporean teachers to examine the level of ICT integration into instruction. Time constraints and curriculum implementation issues were found to affect ICT integration negatively.

2.3 Technical Education Teachers’ Microsoft Excel Skill Competencies

Alazam et al. (2012) explored ICT skill levels of Malaysian teachers and found that Malaysian teachers possessed poor Microsoft Excel skills in relation to their instructional services. Thephavongsa and Liu (2018) found that Laotian teachers had a moderate level of Microsoft Excel skills, yet seldom applied those skills in real-life situations. A quantitative study exploring the Microsoft Excel competency levels of technical education teachers employed descriptive statistics, highlighting the teachers’ limited competence in their application of Microsoft Excel skills (Azih 2016). Kamodi and Garegae (2019) noted teachers’ incompetence using Microsoft Excel skills due to a lack of professional development programmes for teachers. In short, teachers possess varying levels of Microsoft Excel skills depending on the different research designs deployed by different geographical regions.

2.4 Technical Education Teachers’ Internet Skill Competencies

Internet skills are common among students and teachers searching for information, interacting and communicating with each other on social media by using their cellular phones (Voelker 2021). The internet has shifted the traditional face-to-face activities we perform into a virtual mode, transforming industries such as banking, shopping and digital education (Abbott 2001). However, a quantitative study of Malaysian vocational teachers documented their poor level of internet skills (Alazam et al. 2012). Hu, Wong, Cheah, and Wong (2009) surveyed 2,998 Singaporean teachers on internet usage. Teachers and students frequently used e-mail to communicate with each other. In addition, teachers used ICT skills for general purposes such as social media communication (WhatsApp, Facebook, WeChat) as part of internet skills application (Enu et al. 2018).

3 Research Methods

This section describes the processes used to answer research questions scientifically. The process follows this step-by-step procedure:

3.1 Data Collection

Initial data was collected via a questionnaire on ICT needs assessment. Researchers sent letters of consent along with a Google Form to target institutions: 76 vocational-technical high schools/colleges who are members of the 11 Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) network. Member countries asked their technical education teachers to complete the questionnaire in Google Forms. The 11 SEAMEO member countries are: Cambodia, Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, and Vietnam. In addition, the request was sent out by letter to governing board members of Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization Regional Centre for Technical Education Development (SEAMEO TED). A representative of the Ministry of Education coordinated this data collection process in the respective countries. Random sampling was used to collect data from the participants. After a period of over one month, researchers had received sufficient samples for analysis as requested by the deadline.

3.2 Participation Selection

5,704 (n=5,704) technical education teacher participants from the 11 SEAMEO member countries completed the Google Forms questionnaire. The larger sample size supports efforts to generalise results and to decrease error size (Beins & McCarthy 2012). To ensure data generalisation with reliability, population heterogeneity with different sexes, geographical areas, academic levels, age cohorts, work experience, marital status, and some selection criteria were considered. The participants were accessed on the basis of criteria including (1) technical education teachers who are teaching any trade at vocational-technical high schools in any of the 11 SEAMEO member countries; and (2) voluntary participation in filling out the questionnaire in Google Forms. When participants volunteer to participate in a research study, they are willing to use the research tool to the best of their capacities (Beins & McCarthy 2012). The vocational-technical high-schools targeted within the organisation afforded access to participants who identified as technical education teachers.

3.1 Research Instrument

Researchers use the questionnaire in Google Forms adapted from Ramadan, Chen, and Hudson (2018). This meant that content validity was achieved. Content validity refers to a representative of questionnaire items that are measured to achieve pre-determined objectives.

The questionnaire was divided into two sections: (1) ICT skills and (2) demographic information. Questionnaires in Google Forms are far-reaching and widely distributed geographically for more dependable and reliable results (Kothari 2004). The questionnaire had 20 items with a five-point scale for rating. The scale ranges from 1 (strongly incompetent) to 5 (strongly competent). For example, Statement 1 asked about “Producing a text through a word processing programme”. Statement 2 asked about “Using basic word functions”. Statement 20 asked about “I have a social network account (Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Twitter, etc.)”. The demographic information collected included: sex, country origin, age, graduate major, academic degree, marital status, and teaching experience with years of service. This information corroborated a representative sample.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative methodology was employed to analyse data using SPSS v25. The survey design employed a cross-sectional approach which examines current beliefs or practices at one point in time (Creswell 2012). Descriptive statistics such as means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were used to answer pre-identified research questions. To confirm the results of the two research questions, Harman’s single factor test was employed with a magnitude of inter-item correlation within the same construct/factor identified.

3.5 Results

The results emerged from data analysis using SPSS v25 after participants filled out the questionnaire. The 20-item scale reported a reliability Cronbach Alpha of α= 0.977. This meant that the degree was excellent for internal consistency within the scale of all items for further analysis. A reliability coefficient of up to 0.7 is sufficient, whereas a coefficient over 0.9 is considered very satisfactory (Howitt & Cramer 2011).

3.5.1 Demographic Information

The demographic information captured identifying factors of a population to better understand the particular background of the participants. On gender, 37.9% were male, and 62.1% were female. Therefore, the study was female-dominated. The study covered the 11 SEAMEO member countries. The participant-dominated countries in terms of number are Malaysia (80%) and the Philippines (16.8%). Participants’ ages were divided into eight cohorts with their frequencies and percentages. The table highlights a decreasing number of participants based on age from younger to older. It means that the majority of participants from one group (24%) were below 30 years of age. Technical education teachers have earned four types of academic degrees ranging from an associate degree to a doctoral degree. Of the respondents, 81% of participants earned a bachelor’s degree, the standard qualification for becoming a teacher. Technical education teachers’ work experiences, based on years of service, were categorised by cohorts. Young teachers were in the majority. Their cohort, with fewer than 5 years of service, amounted to 32%. This result was consistent with results in a majority of participants’ ages – 24% were below 30 years old. On marital status, 79.7% were married, even though a majority of the participants were young in age.

3.5.2 Major Findings

The major findings related to the pre-identified two research questions: “What are the ICT skills deficiencies of technical education teachers?” and “What are the ICT skills proficiencies of technical education teachers?”. Table 1 specified the number of total participants, means, and standard deviations providing insights for the two research questions. The answers to research question 1 were as follows: ability to use Microsoft Excel to create a database (M=3.19) and (SD=0.875); ease of use in Microsoft Excel (M=3.51) and (SD=0.806); use of Microsoft Excel tools to add up totals on a spreadsheet (M=3.48) and (SD=0.870); and ability to enter numerical data into cells (M=3.60) and (SD=0.853). The answers to research question 2 were as follows: ability to copy and move files into different folders for storage (M=4.01) and (SD=0.844); logging onto the internet (M=4.01) and (SD=0.817); creating, sending and receiving e-mails (M=4.03) and (SD=0.829); adding an attachment to an e-mail (M=4.03) and (SD=0.844); and searching for information using search engines such as Google (M=4.05) and (SD=0.806). Technical education teachers in the 11 SEAMEO member countries have moderate Microsoft Excel skills, but good internet skills.

Tablle 1: ICT Skills Mean and Standard Deviation

| ICT Skill Attribute | N | Mean | SD |

| Producing a text through a word processing program | 5,704 | 3.85 | 0.816 |

| Using basic Word functions | 5,704 | 3.96 | 0.790 |

| Using the toolbar to edit documents by picking font size style | 5,704 | 3.98 | 0.818 |

| Creating cells and tables to display information within a document | 5,704 | 3.91 | 0.829 |

| Saving a document in different file formats (JPEG etc.) | 5,704 | 3.93 | 0.862 |

| Ease using Microsoft Excel | 5,704 | 3.51 | 0.806 |

| Entering numerical data into cells | 5,704 | 3.60 | 0.853 |

| Using Excel tools to add up totals on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet | 5,704 | 3.48 | 0.870 |

| Using Microsoft Excel to create a database | 5,704 | 3.19 | 0.875 |

| Ease organising computer files in a folder and sub-folder | 5,704 | 3.86 | 0.860 |

| Storing files using a USB device or a memory stick | 5,704 | 3.97 | 0.854 |

| Storing information on a CD or DVD | 5,704 | 3.70 | 0.926 |

| Creating and managing files and folders | 5,704 | 3.95 | 0.845 |

| Copying and moving files into different folders for storage | 5,704 | 4.01 | 0.844 |

| Logging onto the internet | 5,704 | 4.01 | 0.817 |

| Searching for information using search engines such as Google | 5,704 | 4.05 | 0.806 |

| Downloading and uploading materials from/to websites | 5,704 | 3.88 | 0.837 |

| Creating, sending and receiving e-mails | 5,704 | 4.03 | 0.829 |

| Adding attachments to an e-mail | 5,704 | 4.03 | 0.844 |

| Owning social network account (Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, YouTube, …) | 5,704 | 3.91 | 0.826 |

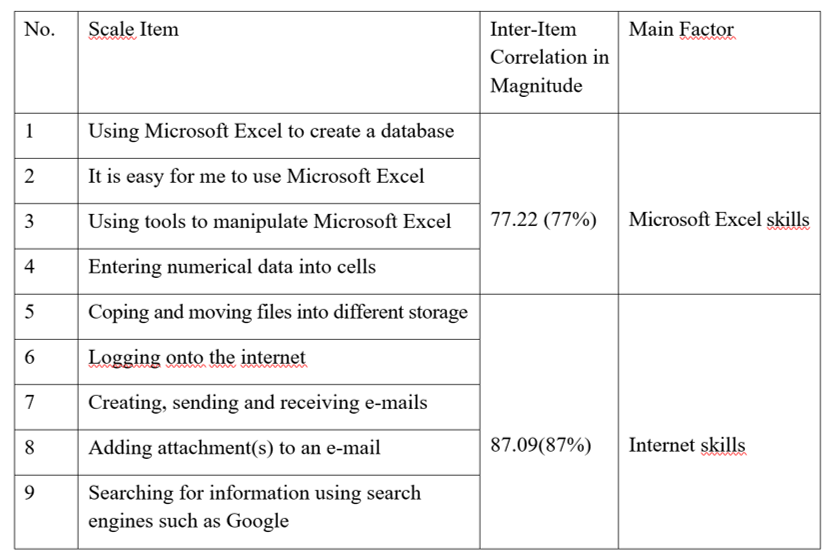

To verify the aforementioned findings, the convergent validity to measure the same construct of correlations at the moderate level of magnitude was used (Kline 2011). The single factor test was employed to check the level of magnitude for both factors identified (Microsoft Excel and internet skills). The outcomes of Harman’s single factor test reflected the same scale items each with their common factor of inter-item correlations, which were more than moderate in magnitude, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Inter-Item Correlation in Magnitude

3.5.3 Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1: There are different competency levels of ICT skills between technical education teachers’ genders (male and female).

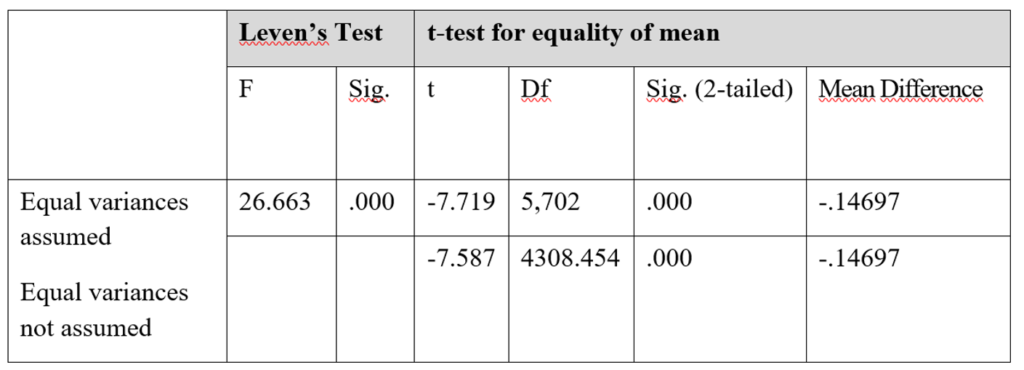

To test hypothesis 1, an independent sample t-test was used, as shown in Table 3. It reflected

t (5,702) =-7.719, p=.000<.05 meaning that it was statistically significant. The result meant that the alternative hypothesis was true, which allowed the study to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, there are different competency levels of ICT skills between technical education teachers’ genders (male and female).

Table 3: Independent Sample t-test Results

Hypothesis 2: There are different competency levels of ICT skills among the 11 SEAMEO member countries.

To test hypothesis 2, one-way ANOVA was used as shown in Table 4. The results reflected F (9, 5,694) =7.003, p=.000<.005 meaning that it was statistically significant, so our research was able to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, there are different competency levels of ICT skills between the 11 SEAMEO member countries.

Table 4: One-Way ANOVA Results

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| Between Groups | 30.685 | 9 | 3.409 | 7.003 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 2771.982 | 5,694 | .487 | ||

| Total | 2802.667 | 5,703 |

Hypothesis 3: There are different competency levels of ICT skills between the cohorts in terms of years of work experience.

To test hypothesis 3, one-way ANOVA was used as shown in Table 5. The results reflected F (4, 5,699) =122.694, p=.000<.05, meaning that the alternative hypothesis was accepted. Therefore, there are different competency levels of ICT skills between the cohorts in terms of participants’ years of experience.

Table 5: One-Way ANOVA Results

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| Between Groups | 222.218 | 4 | 55.554 | 122.694 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 2580.450 | 5,699 | .453 | ||

| Total | 2802.667 | 5,703 |

4 Discussion and Conclusion

The findings suggest that technical education teachers have moderate Microsoft Excel skills, but good internet skills. The internet transforms all areas of life, underscoring socio-economic development and growth towards the digital economy (ASEAN Secretariat 2015). In line with Hypothesis 2, “There are different competency levels of ICT skills among the 11 SEAMEO member countries.” Mia and Habaradas (2020) highlighted the different levels of ICT skill competency as follows: Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia in an achieving stage; Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines in a bridging stage; and Cambodia, Myanmar, and Lao PDR in a nascent stage. Technical education teachers have different ICT skill levels in terms of demographic and geographical characteristics in Malaysia (Alazam et al. 2012). Regional and national policies or strategies support ICT integration following published results ensure that teachers’ ICT competency levels influence their instructional effectiveness (Elstad & Christophersen 2017). For example, a quantitative study assessing the ICT skills needs of Cambodian teachers found that teachers possessed moderate levels of Excel and internet skills (Men 2021). This might be due to different contexts of ICT policies and support systems from country to country.

The results were consistent with previous literature. There were different ICT skills levels among genders and degrees of work experience for Cambodian teachers (Hun et al. 2020). Teachers possess moderate levels of ICT skills for educational integration (Ersoy, Yurdakul, & Ceylan 2016). Indonesian teachers have good internet skills to support instruction (Maryuningsih et al. 2020). Technical education teachers have good Microsoft Excel skills and internet skills (Saripudin et al. 2020). This means that some literature supports the findings that offer a regional perspective in terms of teachers’ ICT competency levels. Therefore, the results might be applicable to regional needs because different countries have their individual ICT supporting systems and frameworks to successfully transition to IR 4.0 skills for teachers.

There are some limitations to consider regarding data generalisation. Although the sample size was especially large for statistical analyses, 80% of the participants are Malaysian teachers, dominating the research study in terms of geographical characteristics. Future research should aim to include more participants from other SEAMEO member countries such as Singapore, Lao PDR, Timor Teste, Indonesia, and Cambodia. Additionally, 42.5% of the participants are under the age of 35. It was consistent with participants’ years of work experience (less than 5 years), represented by 32% of the total participants, so most of the research participants were relatively young. The sample was limited to demographic characteristics. Future research should be undertaken to target older participants to reach a representative sample.

Professional development programmes for technical education teachers, in cooperation with industries providing them with an incentive for active engagement, are recommended. To actualise ICT skills, teachers should link ICT policy directives with the reality of what is currently being implemented in the classroom (UNESCO 2018). A training course on Microsoft Excel should be conducted for technical education teachers by linking lessons learned to work setting needs (Ramadan et al. 2018). Access to digital devices, ICT infrastructure, and teachers’ ICT skills should be enhanced (Voelker 2021). Vocational-technical high schools should have full-scale autonomy in decision-making for their staff’s professional development programmes in terms of budget allocation and management, and cooperation with industries (ADB 2009). ICT skills should be integrated into the curriculum and incorporated into teaching methods, assessment processes, lesson plans, and hand-on activities to create an ICT user-friendly environment (UNESCO 2018). Curriculum modifications and ICT environmental supports should be encouraged to enhance effective ICT integration (Chen et al. 2012). Therefore, it is necessary to examine other factors which can support professional development programmes: ICT infrastructure, high expertise of trainers, internet availability, diversity of training approaches, and motivational systems to influence teachers’ capacities in a positive way.

Skills development is a catalyst to raise productivity and reduce poverty as the right skills are important ingredients for economic development (ADB 2009). With the hope of using and integrating ICT skills into education, the basis of the inclusive knowledge society will be shaped (The HEAD Foundation 2017). Through ICT integration, students from different socio-economic backgrounds and capacities are provided with remedial actions to ensure inclusion with transformative learning approaches (UNESCO 2018). Therefore, the vision of the ASEAN ICT masterplan 2020 will drive ASEAN towards the digital economy and transformation. Sustainability for an inclusive, integrated and innovative ASEAN community will become attainable (ASEAN Secretariat 2020).

References

Abbott, C. (2001). ICT: Changing education. New York: Routledge Falmer.

ADB. (2009). Good practice in technical and vocational education and training. Mandaluyong City: Asian Development Bank. Online: Good Practice in Technical and Vocational Education and Training | Asian Development Bank (adb.org) (retrieved 06.11.2022).

Akarawang, C., Kidrakran, P., & Nuangchalerm, P. (2015). Enhancing ICT competency for teachers in the Thailand basic education system. In: International Education Studies, 8, 6, 1-8.

Alazam, A. O., Bakar, A. R., Hamzah, R., & Asmiran, S. (2012). Teachers’ ICT skills and ICT integration in the classroom: The case of vocational and technical teachers in Malaysia. In: Creative Education, 3, 8, 70-76.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2015). The ASEAN ICT Masterplan 2020. Jakarta: Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Online: Final Review of ASEAN ICT Masterplan 2020 – ASEAN Main Portal (retrieved 05.11.2022).

Azih, N. (2016). Microsoft access and Microsoft Excel skills needed by office technology and management lecturers for quality service delivery. In: International Journal of Business and Social Science, 7, 5, 193-199.

Beins, B. C. & McCarthy, M. A. (2012). Research methods and statistics. New Jersey: Pearson.

Becker, M., Spöttl, G., & Windelband, L. (2022). The role of artificial intelligence in skilled work and consequences for vocational training. In: TVET@Asia, issue 19, 1-15. Online: The role of artificial intelligence in skilled work and consequences for vocational training | TVET@Asia (tvet-online.asia) (retrieved 06.11.2022).

Brown, T. (2020). The importance of information and communication technology (ICT). Mississauga: IT Chronicles Media. Online: https://itchronicles.com/information-and-communication-technology/the-importance-of-information-and-communication-technology-ict/ (retrieved 10.10.2022).

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.) Boston: Pearson.

Elstad, E. & Christophersen, K. A. (2017). Perceptions of Digital Competency among Student Teachers: Contributing to the Development of Student Teachers’ Instructional Self-Efficacy in Technology-Rich Classrooms. In: Education Sciences, 7, 1, 1-15.

Enu, J., Nkum, D., Ninsin, E., Diabor, C. A., & Korsah, D. P. (2018). Teachers’ ICT skills and ICT usage in the classroom: The case of basic school teachers in Ghana. In: Journal of Education and Practice, 9, 20, 35-38.

Ersoy, M., Yurdakul, I. K., & Ceylan, B. (2016). Investigating preservice teachers’ TPACK competencies through the lenses of ICT skills: An experimental study. In: Education & Science, 41, 186, 119-135.

Fu, J. (2013). ICT in education: A critical literature review and its implications. In: International Journal of Education and Development Using ICT, 9, 1, 112-125.

Habaradas, R. B. & Mia, B. R. (2020). ASEAN ICT developments: Current state, challenges, and what they mean for SMEs. In: Philippine Academy of Management E-Journal, 3, 1, 37-50.

Hakkarainen, K., Muukonen, H., Lipponen, L., Ilomäki, L., Rahikainen, M., & Lehtinen, E. (2001). Teachers’ information and communication technology (ICT) skills and practices of using ICT. In: Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 9, 2, 181-197.

Hanushek, E. A. & Woessmann, L. (2011). The economics of international differences in education achievement. In: Handbook of Education Economics, 3, 2, 89-200.

Hatlevik, O. E, Egeberg, G., Gudmundsdottir, G. B, Loftsgaarden, M., & Loi, M. (2013). Monitor Skole: Om digital kompetanse og erfaringer med bruk av IKT i skolen. Utdanningen: Senter for IKT I.

Howitt, D. & Cramer, D. (2011). Introduction to statistics in psychology (5th ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Htun, K. S. (2019). An investigation of ICT development in Myanmar. In: The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 85, 2, 1-19.

Hu, C., Wong, A. F., Cheah, H. M., & Wong, P. (2009). Patterns of email use by teachers and implications: A Singapore experience. In: Computers & Education, 53, 3, 623-631.

Hue, L. T. & Ab Jalil, H. (2013). Attitudes towards ICT integration into curriculum and usage among university lecturers in Vietnam. In: International Journal of Instruction, 6, 2, 53-66.

Hun, R., Shimizu, K., & Kao, S. (2020). Cambodian teacher educators’ attitudes towards the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in education: Trends and patterns. In: Journal of International Development and Cooperation, 27, 1, 1-15.

Ilomäki, L. & Lakkala, M. (2018). Digital technology and practices for school improvement: innovative digital school model. In: Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 13, 1, 1-32.

Joo, L. (2018). Vol. 2: The excellence of technical vocational education and training (TVET) institutions in Korea: Case study on Busan national Mechanical Technical High School. In: International Education Studies, 11, 11, 69-87.

Kamodi, T. L. & Garegae, K. G. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions on use of Microsoft excel in teaching and learning of selected concepts in junior secondary school mathematics syllabus in Botswana. In: Lonaka JoLT, 10, 1, 67-81.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Delhi: New Age International.

Lee, J. W. (2020). Human capital development in South Asia. In Panth, B. & Maclean, R. (eds.): Anticipating and Preparing for Emerging Skills and Jobs. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer, 33-39.

Lopes, B., Lucas, M., Albergaria-Almeida, P., & Martinho, M. (2017). Training Timorese science teachers in the context of international cooperation: What role could ICT play? In: Conexão Ciência, 12, 416-423.

Lubis, M. A., Lampoh, A. A., Yunus, M. M., Shahar, S. N., Ishak, N. M., & Muhamad, T. A. (2011). The use of ICT in teaching Islamic subjects in Brunei Darussalam. In: International Journal of Education and Information Technologies, 5, 1, 79-87.

Marcial, D. E. & Rama, P. A. (2015). ICT competency level of teacher education professionals in the Central Visayas Region, Philippines. In: Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3, 5, 28-38.

Maryuningsih, Y., Hidayat, T., Riandi, R., & Rustaman, N. Y. (2020). Profile of information and communication technologies (ICT) skills of prospective teachers. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1521, 1-7. Online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/1521/4/042009 (retrieved 07.11.2022).

Mundia, L. (2020). Assessment of skills development in Brunei trainee teachers: Intervention implications. In: European Journal of Educational Research, 9, 2, 685-698.

Napal, F. M., Peñalva-Vélez, A., & Mendióroz, L. A. M. (2018). Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training. In: Education Sciences, 8, 3, 1-12.

Park, C. Y. & Kim, J. (2020). Education, Skill Training, and Lifelong Learning in the Era of Technological Revolution. In: ADB Economics Working Paper Series, 606. Manila: ADB.

Ramadan, A., Chen, Z., & Hudson, L. L. (2018). Teachers’ skills and ICT integration in technical and vocational education and training TVET: A case of Khartoum state-Sudan. In: World Journal of Education, 8, 3, 31-43.

Ratheeswari, K. (2018). Information communication technology in education. In: Journal of Applied and Advanced Research, 3, 1, 45-47.

Røkenes, F. M. & Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Development of student teachers’ digital competence in teacher education – A literature review. In: Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9, 04, 250-280.

Samuel, O. G., Caleb, E. E., & Touitou-Tina, C. (2016). The Technical Teacher, Teaching and Technology: Grappling with the Internationalization of Education in Nigeria. In: International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, 2, 4, 259-265.

Samuel, R. J. & Zaitun, A. B. (2007). Do teachers have adequate ICT resources and the right ICT skills in integrating ICT tools in the teaching and learning of English language in Malaysian schools? In: The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 29, 1, 1-15.

Saripudin, S., Sumarto, S., Junala, E. A., Abdullah, A. G., & Ana, A. (2020). Integration of ICT skill among vocational school teachers: A case in west Java, Indonesia. In: International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, 9, 5, 251-260.

Tjoa, A. M. & Tjoa, S. (2016). The role of ICT to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). In Mata, F. & Pont, A. (eds.): WITFOR 2016: ICT for Promoting Human Development and Protecting the Environment. Cham: Springer, 3-13.

UNESCO. (2018). ICT competency framework for teachers. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265721 (retrieved 02.12.2022).