Abstract

The phenomenon of Industry 4.0 accompanied by the COVID-19 pandemic has shocked the world community, including the world of vocational education. The challenge facing vocational education globally is to align learning programmes with the high demand for skills in industry, whilst narrowing the gap to industrial needs in educational institutions. Since 2019, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the logistics industry has increased its income compared to other industries. This is a great opportunity for logistics vocational education to prepare students with the requisite skills that the logistics industry is looking for. This requires an upgraded curriculum, updated methods and tools for learning programmes that correspond to the skills needed by the logistics industry. This study aims to capture the skills needed by the logistics industry. However, the purpose of vocational education/Vocational High School (SMK) is to prepare graduates who are ready to work and have skills according to the needs and demands of the industry. These skills cannot be prepared in a short space of time, particularly as changes in the industrial world occur rapidly and massively. SMK must be able to answer the challenges of industry through various innovations in preparing graduates who are skilled and highly competitive in the logistics industry.

Keywords: Logistics Industry, Skills Worker, Vocational Education

1 Introduction

Vocational education is an institution that aims to prepare graduates to enter and compete in the industrial market. In Indonesia, however, vocational education is the largest contributor to unemployment, starting from taxation for vocational education goals. Research in the Philippines came up with similar findings (Vandenberg & Laranjo 2020). Education does not necessarily lead to the intended outcomes for the labour market (Jules 2015; Temjanovski & Arsova 2020). On the demand side, an individual may pursue a course of study for which employers are not hiring. The jobseeker falls victim to what is known as a horizontal skills gap. On the supply side, the poor quality of education in terms of curriculum, facilities, or teaching, may result in very little learning actually taking place (Marinho & Delgado 2019). Employers may perceive that graduates have limited knowledge and few skills (Okolie et al. 2019; Temjanovski & Arsova 2020). Logistics is a progressive industry which accelerated and expanded during the pandemic conditions of 2020. The world became increasingly dependent on logistics in the midst of the pandemic era (Vandenberg & Laranjo 2020).

2 Study Focus and Methodology

This study aims to look at the competencies needed by the logistics industry and the role of vocational education (SMK) in preparing graduates according to the needs of the logistics industry. The method used in this study is qualitative research with a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) approach involving SMK, the logistics industry, and curriculum experts. The FGD used implementation guidelines that were prepared prior to FGD. A review was carried out to clarify the research findings of the study and highlight certain ideas. Meeting the challenge outlined above involves optimizing the readiness of Logistics Vocational School graduates with vocational learning concepts that are relevant to the needs of the logistics industry.

3 Overview Logistics Skills Industry Needed

Logistics engineering is a professional engineering discipline which deals with integration support in design and development, testing and evaluation, production, construction, operation, maintenance, and, ultimately, disposal/recycling of systems and equipment. Logistics management plans, implements, and controls the efficient, effective forward and reverse flow and storage of goods, services, and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet customer’s requirements in the supply chain (Vandenberg & Laranjo 2020). Logistics, especially in the field of education, is currently not accommodating the needs of industry, as demonstrated in earlier research in the United States (Hughes et al. 2017). In the competitive global economy, there will be increasing demand for highly qualified workers to create efficient industrial logistics systems (Truong & McColl 2011; Waller 2012).

Logisticians analyze and coordinate an organization’s supply chain – the system that moves a product from supplier to consumer (Ellinger & Ellinger 2014). They manage the entire life cycle of a product, which includes how a product is acquired, allocated, and delivered. Logisticians typically manage a product’s life cycle from design to disposal, direct the allocation of materials, supplies, and products, develop business relationships with suppliers and clients, understand clients’ needs and how to meet them, review logistical functions and identify areas for improvement, propose strategies to minimize the cost or time required to transport goods (Goffnett et al. 2012). Logisticians oversee activities that include purchasing, transportation, inventory, and warehousing. They may direct the movement of a range of goods, people, or supplies, from common consumer goods to military supplies and personnel. Logisticians use software systems to plan and track the movement of products (Graca et al. 2015). They operate software programmes designed specifically to manage logistical functions, such as procurement, inventory management, and other supply chain planning and management systems. Research has identified logistician skills that vocational students would need to prepare them for work in the logistics industry. These are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Logistician Skills Needed

| No | (Wagner et al. 2020) | (Thai et al. 2011) | (Goffnett et al. 2016) | (McKinnot et al. 20217) |

| 1 | Negotiating Skills | Understanding Technologies | Analytical Skills | Communication |

| 2 | Managing Stress | Ability to delegate | Communication | Negotiation |

| 3 | Presentation Skills | Traffic/transport management | Problem Solving | Leadership |

| 4 | Leadership Skills | Effective supervision of staff | Leadership | Problem Solving |

| 5 | Critical Thinking Skills | Occupational health and safety | Negotiation Skills | Honesty |

| 6 | Conflict Management | Strategic management | Financial Analysis | Analytic Skills |

| 7 | Time Management | Risk management | Creative Thinking | Teamwork |

| 8 | Self Development | Communication | Technical Capability | Relationship |

| 9 | Oral Communication | Personal integrity | Ability to learn quickly | Ability to delegate |

| 10 | Teamwork | Knowledge of two or more languages | Change management | |

| 11 | Ability to prioritize | Problem-solving ability | Project Management | |

| 12 | Comfortable with change | Self-motivation | Relationships | |

| 13 | Individual Time Management | Big Picture | ||

| 14 | Ability to handle intense pressure | |||

| 15 | Measurement/Assessment |

Table 1 presents a list of logistician skills needed in the logistics industry (from earlier research). People who aim to work in the logistics industry should include these skills in their preparation. The Vocational School (SMK) seeks to help students prepare their skills to become proficient logisticians and meet the demands of the logistics industry. Some skills take longer to acquire and involve lengthier spells in practical situations beyond formal education.

4 Vocational Education (SMK) to prepare Logistics Skills

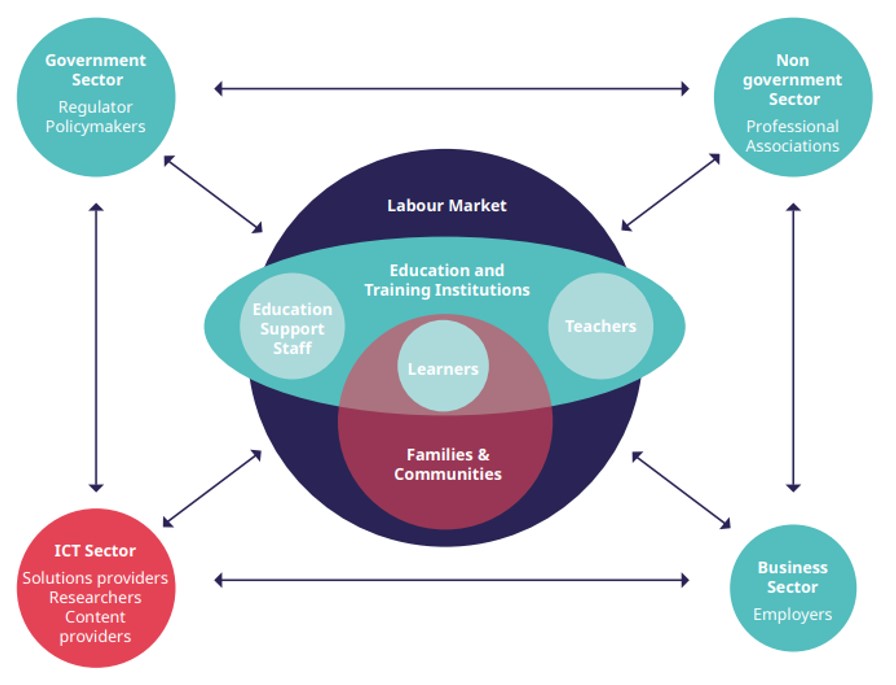

In many countries, distinct systems of TVET and academically oriented education operate side by side, often with different rules for quality assurance, funding, staffing, credits, and qualifications (Leon & Uddin 2016). On a programme level, it is often harder to distinguish between TVET and academic education, as they both employ similar approaches to teaching, with the same generic aims and methods (Partida 2014). A traditional view of educational systems conflates knowledge development with academically oriented education and skills development within TVET. However, academically oriented education is increasingly expected to show direct relevance to the labour market, while skills development is not just limited to technical knowledge and aptitude, but increasingly focusses on ‘softer’ skills such as communication, digital and media literacies, critical thinking, negotiation, and teamwork. In such a context, it is useful to think of the role of digital transformation in skills systems which involve multi-stakeholder partnerships breaking down competencies into discrete units that are learned, practised, and developed in a lifelong context across formal education, employment, and personal life. Technical and Vocational Education Training (TVET) is preparing in every global aspect to function as a bridge between institutional education and industry to supply and demand. In Indonesia, SMK is one of the formal TVETs that prepare students to work in industry. International Labour Organization (ILO) has outlined the TVET system in Figure 1.

Figure 1 presents a collaboration between government, non-government, professional associations, TVET institutions, and communities. Building TVET skills needs multi-stakeholder involvement. The logistics field is a new field of TVET in Indonesia, where SMK and some non-formal TVETs such as Badan Latihan Kerja (BLK) have prepared logistics TVET. SMK has looked at how to prepare a curriculum, methodology and collaborations between SMK and industry. Students need some form of recognized certification to prepare them for the logistics industry. Some SMKs have prepared their own certification. In the logistics sector, figure 1 shows it is important to prepare students’ skills or competitive capabilities through collaboration of government, non-government, the ICT sector and business sector, thus building quality education for learners and teachers with support from families and communities. Collaboration with the ICT sector and certification can be done via E-Certification to assess certain skills (Samara 2021).

5 Collaborative Learning Between Vocational Education and Logistics Industries

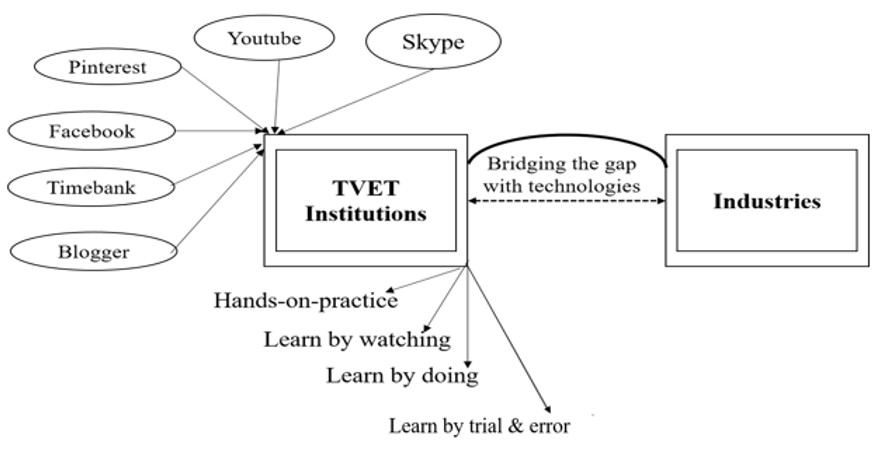

TVET must get closer to industry in general and, for the purposes of this study, to logistics industries in particular., Many activities in logistics industries are developed through digitalization, like learning, working, purchasing, etc. TVET should prepare a way to bridge the gap between TVET institutions and industries. In the pandemic era, TVET is compelled by the situation to optimize technology in many areas. A clearer picture of how collaboration between TVET and industries can work is presented in Figure 2.

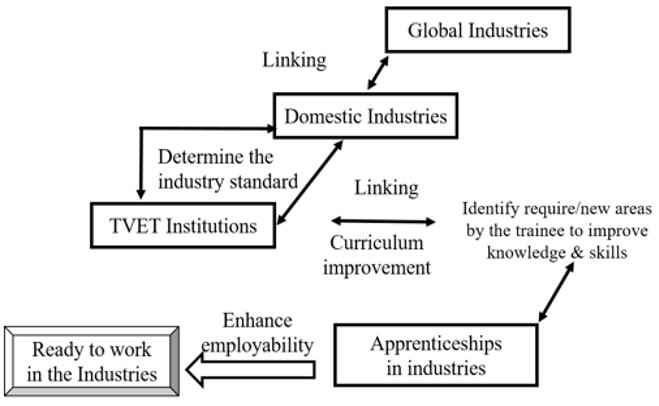

The collaboration of TVET and industries requires optimization of technology to bridge the gap. Online platforms can be used jointly without constraints of time or place (Bag, Gupta, & Luo 2020). Figure 2 shows that more online platforms help TVET institutions to provide learning experience with industries (Albashiry et al. 2015; Alipour & Newton 2019). Hands on-practice, learning by watching, learning by doing, and learning by trial and error are four activities that can be conducted online. The pandemic era has seen an acceleration of learning activities with greater use of applications, online platforms, and other technology to support them. Tools are key to reaching learning goals and the pandemic has led to increased use of technology to solve problems in TVET such as distance or time. Innovative approaches (Ahmed et al. 2020), as presented in figure 3, can solve problems like reinforcing links between TVET institutions and industries. Collaboration is an answer to most problems and gaps in TVET and logistic industries. Figures 3 and Figure 4 explore collaboration in more detail.

Based on figure 3, collaboration between TVET and industries is one of the keys to developing a TVET curriculum that matches industrial demand. Collaboration is also a good way to collect more information on what industry needs (Ayonmika et al. 2015). Demands on workers in the field are high, especially for the vocational graduate, but certification in Indonesia does not mean the path to work is straightforward (Bekri, R. M, et.al. 2015; Boateng, C 2012). The authors conducted discussions with several experts in the logistics field as a further step of research. These discussions highlighted competencies and certifications that would be needed to support the opening of opportunities for Vocational High School graduates in the field of logistics engineering and help them to compete in the world of work (Adimas et al. 2021).

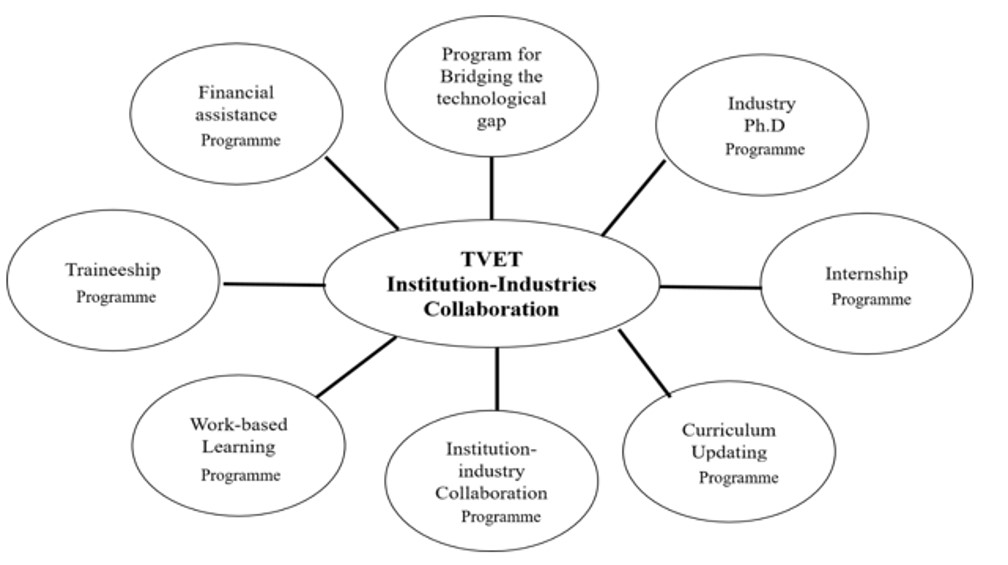

Figure 3 shows that each level of industry must collaborate with TVET institutions like SMK. To bridge the gap between industries and TVET institutions and to provide better service for both sides, logistic industries should collaborate with TVET or SMK on programmes to support teachers and students. Industries could also get more involved in the curriculum and learning activities. One of SMK’s goals is to prepare students to work in logistic industries. These industries have comprehensive lists of skills for logistic workers. How to structure effective collaboration is a big question, but it is not a hard question to answer. Technology has helped us to answer some questions already and today it is possible to increase collaborative activities simultaneously across different locations, some quite remote from each other. This will enable students to access authentic information from logistic industries. Training/internships help students gain experience, experts from logistic industries can support us as supervisors or mentors in learning activities. Key to this collaboration is an updated TVET curriculum that addresses supply and demand between TVET and logistic industries. Further details are shown in Figure 4.

Logistics experts state that basic science and basic engineering are the main foundations before learning more about logistics engineering (Rosina et al. 2021). Logistics practitioners noted that certification would bring added value for graduates as confirmation that their competencies had been tested through a validated process (Chan Lin, L.-J. & Hung, W.-H.,2015). Certification examiners agreed that graduates will be better equipped and prepared for work if they have a diploma and certificate in the form of competency test results from the certification process. Certification examiners for Vocational High School graduates added that graduates with certificate of competence would have a competitive advantage in industry over graduates who do not take a certification test for competency.

Besides certification in the TVET curriculum, a collaboration between figure 2 and table 1 would also serve to prepare student’s skills. It is important for TVET students to have the full list of logistician skills at their disposal. This study explores vocational education collaboration with industries to develop a curriculum, whilst involving industries in learning activities as supervisors, partners, and teachers. Technology can bridge the gap for vocational education, overcoming challenges of time and place. Online and offline training methods are deployed in most industries. This is conducive to building effective collaboration between vocational education and logistics industries. TVET institutions have adopted technology in learning processes more rapidly during the pandemic, as shown in figure 2. More applications can be used for learning activities. In the future, guidelines must be developed to determine the right methods for TVET learning – working towards positive output and outcomes for practical, cognitive and affective aspects such as good attitude, communication and work skills. TVET institutions such as SMK must embrace innovation to optimize TVET learning output and outcomes to face the challenges posed by the fast-moving logistic industries challenges and the rapidly evolving skills they demand. Vocational education can prepare TVET students with the requisite skills to become efficient workers in logistic industries. Some problems can be solved by technology and positive collaboration between TVET institutions and logistic industries. Working together, they can build TVET systems that address the supply and demand of logistics industries. This supports TVET’s mission to produce competent graduates who can work in logistics industries, and help logistics industries improve their services with an inflow of talented workers. Governmental collaboration with TVET and logistics industries will boost the economic sector and potentially reduce unemployment numbers.

6 Conclusion

To conclude, the author sees collaboration as a means to prepare vocational education (SMK) with the means to answer the needs of logistics industries. It is not easy to become a good logistician, so vocational education should intensify collaboration to address the list of skills that logistic industries expect their workforce to possess. Using technology to link up participants can benefit the collaborative process. Learning activities can take place online and offline, with greater flexibility in the event of unexpected conditions. Technology can support learning through observation, action or hands-on practical tasks. Involving logistics industries in SMK learning activities is one of the successful keys to answering logistics demand and corresponds to SMK’s goal to prepare students for work in the industry. Most of the skills on the list are soft skills that cannot be prepared in a short space of time, so SMK or TVET institutions must optimize collaboration between TVET and logistic industries with technological solutions for learning activities.

References

Ahmed, S., Islam, H., Hoque, I., & Hossain, M. (2020). Reality check against skilled worker parameters and parameters failure effect on the construction industry for Bangladesh. In: International Journal of Construction Management, 20, 5, 480–489.

Albashiry, N. M., Voogt, J. M., & Pieters, J. M. (2015). Improving curriculum development practices in a technical vocational community college: examining effects of a professional development arrangement for middle managers. In: Curriculum Journal, 26, 3, 425–451.

Alipour, P., & Newton, K. (2019). Development of Curriculum in Technology-related Supply Chain Management Programs. 126th Annual Conference & Exposition ASEE.

Ayonmika, C.S., Chijioke, O. P., & Okeke, B. C. (2015). Towards Quality Technical Vocational Education and Training (Tvet) Programmes in Nigeria: Challenges and Improvement Strategies. In: Journal of Education and Learning, 4, 1, 25-34.

Bag, S., Gupta, S., & Luo, Z. (2020). Examining the role of logistics 4.0 enabled dynamic capabilities on firm performance. In: International Journal of Logistics Management, 31, 3, 607–628.

Bekri, R.M. et al., (2015). The Formation of an E-portfolio Indicator for Malaysia Skills Certificate: A Modified Delphi Survey. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, pp.290–297.

Boateng C. (2012). Leadership Styles and Effectiveness of Principals of Vocational Technical Institutions in Ghana. American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 128-134.

ChanLin, L.-J. & Hung, W.-H., (2015). Evaluation of An Online Internship Journal System for Interns. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, pp.1024–1027

Ellinger, A. E. & Ellinger, A. D. (2014). Leveraging Human Resource Development Expertise to Improve Supply Chain Managers’ Skills and Competencies. In: European Journal of Training and Development, 38, ½, 118-135.

Firmansyah, A., Samsudin, A. F., Aqmal, R. Y., Sasmita, A. H., & Dwiyanti, V. (2021). E-Learning Methods Impact in Vocational Education. In: INVOTEC, 17, 1, 14-21.

Goffnett, S. P., Williams, Z., Gibson, B. J., & Garver, M. S. (2016). Identifying critical skills for logistics professionals: Assessing skill importance, capability, and availability. In: Journal of Transportation Management, 27, 1, 45-61.

Goffnett, S. P., Cook, R. L., Williams, Z., & Gibson, B. J. (2012). Understanding Satisfaction with Supply Chain Management Careers: An Exploratory Study. In: International Journal of Logistics Management, 23, 1, 135-158.

Graca, S. S., Barry J. M., & Doney, P. M. (2015). Performance outcomes of behavioral attributes in buyer-supplier relationships. In: Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 30, 7, 805–816.

ILO. (2020). The Digitalization of TVET and Skills System. Geneva: ILO.

Jules, T. D. (2015). Educational exceptionalism in small (and micro) states Cooperative educational transfer and TVET. In: Research in Comparative and International Education, 10, 2, 202–222.

Leon, S. & Uddin, N. (2016). Finding Supply Chain Talent: An Outreach Strategy. In: Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21, 1, 20-44.

Marinho, P. & Delgado, F. (2019). A Curriculum in Vocational Courses: The Recognition and (Re)Construction of Counterhegemonic Knowledge. In: Educational Forum, 83, 3, 251–265.

McKinnon, A. C., Hoberg, K., Petersen, M., & Busch, C. (2017). Assessing and improving countries’ logistics skills and training. In Jahn, C., Kersten, W., & Ringle, C. (eds.): Digitalization in Maritime and Sustainable Logistics: City Logistics, Port Logistics and Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Digital Age. Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), 24, 97-117.

Okolie, U. C., Igwe, P. A., & Elom, E. N. (2019). Improving graduate outcomes for technical colleges in Nigeria. In: Australian Journal of Career Development, 28, 1, 21–30.

Partida, B. (2014). Supply Chain Talent Development Is A Work In Progress. In: Supply Chain Management Review, 18, 1, 55-57.

Raihan, A. (2014). Collaboration between TVET Institutions and Industries in Bangladesh to Enhance Employability Skills. In: International Journal of Engineering and Technical Research (IJETR), 2, 10, 50-55.

Rosina, H., Virgantina, V., Ayyash, Y., & Dwiyanti, V. (2021). Vocational Education Curriculum: Between Vocational Education and Industrial Needs. In: ASEAN Journal of Science and Engineering Education 1, 2, 105-110.

Samara, M. (2021). Towards e-learning in TVET: Setting and developing E-Competence Framework for TVET teachers in Palestine. In: TVET@Asia, issue 16, 1-15. Online: https://tvet-online.asia/wp content/uploads/2021/02/Samara_issue_16_TVET.pdf (retrieved 10.02.2021).

Temjanovski, R., & Arsova, M. (2020). Logistics Education in Universities in 21st Century : New Trends and Challenges. 8th International Scientific Conference Technics and Informatics in Education September. Čačak: Faculty of Technical Sciences.

Thai, V. V., Cahoon, S., & Tran, H. T. (2011). Skill requirements for logistics professionals: findings and implications. In: Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and logistics, 23, 4, 553-574.

Truong, Y. & McColl, R. (2011). Intrinsic motivations, self-esteem, and luxury goods consumption. In: Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 6, 555–561.

Vandenberg, P. & Laranjo, J. (2020). The Impact of Vocational Training on Labor Market Outcomes in the Philippines. ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 621. Manila: ADB.

Wagner, C., Sancho Esper, F., & Rodriguez Sanchez, C. (2020). Skill and knowledge requirements of entry-level logistics and supply chain management professionals: A comparative study of Ireland and Spain. In: Journal of Education for Business, 95, 1, 23-36.

Winch, C. (2015). Towards a framework for professional curriculum design. In: Journal of Education and Work, 28, 2, 165–186.

Winkelhaus, S. & Grosse, E. H. (2020). Logistics 4.0: a systematic review towards a new logistics system. In: International Journal of Production Research, 58, 1, 18–43.

Yusuf, M.A. & Soyemi, J. (2012). Achieving sustainable economic development in Nigeria through technical and vocational education and training: the missing link. In: International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2, 2, 71-77.