Abstract

Unemployment is an issue, particularly for out of school young people, that the Cambodian Government through the Ministry of Labour & Vocational Training (MoLVT) is seeking to address. This challenge is compounded for young people in rural communities – particularly for those who may have a disability, have limited school education or are from ethnic minority communities. The 4 year Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People (VTDYP) project initiated as a partnership among PLAN INTERNATIONAL, Regional / Provincial Training Centers and MoLVT between 2014 – 2017 sought to address this issue within the Ratanakiri, Siem Reap Tboung Khmum provinces in Cambodia. The project, funded by DFAT, was implemented by PLAN INTERNATIONAL CAMBODIA through PLAN INTERNATIONAL AUSTRALIA.

The research investigated the project’s “Comprehensive Training” model which was underpinned by a holistic, learner-focused approach that focused on the identification of the neediest young people within targeted communities and engaged them in experiential learning that would enable them to gain employment or start their own business relatively quickly. Using an investigative process that included document analysis, semi-structured interviews with 41 respondents and on-site observations, the research identified 12 practices, spread across the pre-training, training and post training phases of the VTDYP, that were key features of the project and could be considered for initiatives of a similar kind in Cambodia. While the good practices identified in the research are acknowledged, a number of areas for improvement were also identified and these are also discussed.

Key Words: TVET for disadvantaged youth, provider-enterprise partnerships, TVET in rural Cambodia, poverty reduction through small business

1. Introduction

The emerging interest in TVET as a pro-poor investment strategy is well justified in Cambodia (OECD 2017, 9). Marginalized groups including those with disabilities or ethnic minority young people – especially women – have difficulty accessing formal TVET programs. This study perceives “disadvantage” as the degree of difficulty being experienced by young people in transitioning from school to employment or from unemployment to employment. The young people aged 15-24 years participating in the program were educationally disadvantaged in that, for a variety of socio-economic, cultural, attitudinal or demographic reasons, their primary school experience had been cut short or ineffective in developing the knowledge and skills required for continuing education or employment. Disadvantage as it relates the cohort of young people in question is therefore influenced by the complex relationships among socio-economic, institutional and individual factors that create barriers to economic security and ongoing personal development (Walther and Pohl 2005, 35). Without solid education foundations (Searin 2015, 4) and formal vocational education and training they are denied the technical and soft skills, that is “work readiness” (ADB 2016, 5) to earn a decent income. It is important that TVET initiatives that are successfully addressing this challenge are documented and shared. Although research exists on generic TVET good practices (ADB 2009), TVET’s role in sustainable development (Paryono 2017) and trainer professional development (Axmann et al 2015), only few studies relating to good practices in Cambodia’s PTCs exist (an example being CDRI 2015). The good practices that emerged from the VTDYP, described below, serve to extend this knowledge. The good VTDYP practices – including enterprise-based training, soft skill training and disability mainstreaming could:

− be utilized in future similar programs

− serve as benchmarks for other organizations to consider – and hopefully surpass – in the spirit of continuous improvement

− showcase the achievements of participating R/PTCs

− support PLAN INTERNATIONAL’s onion good practice strategy that includes documentation, video, website and the social media (PLAN 2017a, 9).

2. Research Methodology

The study sought good practices within the VDTYP as it operated across the provinces of Tboung Khmum, Siem Reap and Ratanakiri while also promoting ongoing organizational learning within each PTC. While the study did not seek to evaluate practices or to compare practices with other TVET providers or national/international standards, it was important to determine from the outset what was meant by “good practice”. In this study a ‘good practice’ is one that contains one or more of the following requirements:

|

|

Category |

Requirement |

|

Trainee welfare |

The practice assures trainee safety and wellbeing |

|

|

Trainee expectations |

The practice meets the expectations and requirements of the trainee |

|

|

Trainee development |

The practice promotes progressive trainee learning and development (knowledge, skills and competencies) |

|

|

Inclusiveness |

The practice respects diversity and inclusiveness by meeting the individual learning needs of trainees |

|

|

Cultural sensitivity |

The practice is culturally sensitive and socially appropriate |

|

|

Strategic alignment |

The practice aligns with MoLVT guidelines and policy requirements |

|

|

Standards oriented |

The practice reflects industry standards relating to management, industry, product and service quality |

Figure 1: Good Practice requirements

Secondary information/data accessed during the study included the project proposal, project progress reports, evaluation reports, a mid-term review report, project disability inclusion guidelines as well as reports on international initiatives associated with TVET for OSY.

Primary data was sought through in-depth semi-structured interviews with individuals or small groups seeking the perspectives of the various stakeholders. Each interview was conducted in Khmer by two researchers, with responses being translated into English both during and immediately after each interview. Interviews with R/PTC staff members were conducted collectively to include the Director/ Deputy Director, Soft Skills Trainers, Community Development Specialists and K Job Placement Officers. Interviews with graduates were conducted on an individual basis, or in pairs or trios, at either their village business or town-base employment location, or centrally at the respective PTC. All interviews with enterprise trainers were held on their business premises.

Interview questions investigated 20 areas of program delivery across the pre-training, training and post-training program components of the program, as outlined in Figure 2 below.

|

|

Question category |

Question example |

|

PRE TRAINING |

||

|

1. |

Program has a clear purpose and rationale. |

What is the purpose of the program? |

|

2. |

Program pre-course information is timely, accurate and accessible to the target group. |

What pre-course information was provided to potential trainees? How was this done? |

|

3. |

Program included learners drawn from the specified target group. |

What were the target groups from which trainees were drawn? How were these trainees identified? |

|

4. |

Industry is involved in verifying the authenticity of the training program. |

In what ways was industry involved in the planning, development and implementation of the program? |

|

5. |

Trainees are successfully oriented into the program. |

What orientation was provided to new trainees? |

|

6. |

Program aligns with MoLVT strategic policy requirements. |

How does the program align with MoLVT policy requirements? |

|

TRAINING |

||

|

1. |

Course duration is appropriate for the competencies to be developed and qualification to be achieved. |

What is the duration of the program in weeks? |

|

2. |

Course model/s and environment suits the different learning need of trainees. |

In what ways was the program delivered to trainees? (center based, enterprise based, other) |

|

3. |

Curriculum for each industry includes specific technical competencies. |

In what industries were trainees enrolled? What specific competences were taught in reach industry area? |

|

4. |

Curriculum for each industry includes specific soft skill competencies. |

What soft skills were taught as part of the program? How were these taught? |

|

5. |

Training equipment and hardware aligns with current industry and safety requirements. |

What specific training hardware exists for each industry within the program? How is safety assured when trainees use machinery or other equipment? |

|

6. |

Trainers have the relevant technical qualifications and industry experience. |

How are trainers recruited? What are the minimum requirements for trainer qualifications and experience? |

|

7. |

Assessment provides evidence of competency achievement. |

How is trainee competency assessed? What levels of flexibility exist within this strategy to meet individual student needs? |

|

8. |

Trainee complaints, concerns and grievances are resolved quickly. |

How many trainee complaints were received during the program? How are trainee complaints or concerns managed? |

|

9. |

Trainee accommodation and safety arrangements are in place. |

What accommodation arrangements are in place for trainees? How are these arrangements monitored? |

|

10. |

Learning materials and manuals are user-friendly and up-to-date. |

What learning materials / manuals are provided to trainees to support their learning? |

|

11. |

Student services and counselling are available to support trainee social development. |

What services (like counselling, tutoring or medical assistance) are available to trainees during the program? |

|

POST TRAINING |

||

|

1. |

Program graduates are work ready and employable in their chosen industry field. |

In what was did the program ensure that graduates are “work ready” in their chosen occupation? |

|

2. |

Certification and recognition are provided to program graduates. |

At what CQF level do trainees graduate from the program? How was this certificate awarded? |

|

3. |

Program graduates have gained dignified employment. |

How many of the graduates have achieved dignified employment as a result of the program? |

Figure 2: Good Practice interview question categories

Altogether 41 people were interviewed either individually or in small groups to gather data pertaining to good TVET practice. Prepared data gathering sheets were developed for each individual or group to be interviewed – Director, soft skills trainers, enterprise trainers, graduates and employers. Of the 13 graduates interviewed 8 were female, and occupations covered sewing (4), tailoring (2), cook (2), motorbike repairs (2), electrical wiring (1), hair dressing (1) and welding (1).

Table 1: Interview participants in the VTDYP

|

Gra-duate |

Enter-prise Trainer / Owner |

Director |

R/PTC trainers & Staff |

CDF |

JPO |

Total |

|

|

Ratanakiri |

4 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

|

Siem Reap |

6 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

Tboung Khmum |

3 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

|

Total |

13 |

13 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

41 |

However, while the study did identify good practices and areas for improvement, it needs to be pointed out that graduates interviewed were not randomly selected but chosen because of their availability and ability to demonstrate the intended outcomes of the program. No graduates with an identified disability participated in the study and limited time (approximately 45-60 minutes) was available for each interview with graduates.

3. VTDYP Project Model Overview

3.1 Goal and Objectives

The purpose of the VTDYP aligned with broader international initiatives such as UNESCO’s strategic intention to foster youth employment and entrepreneurship, promote equity and gender equality as well as facilitate the transition to green economies and sustainable societies (UNESCO 2016, 7). Implementing partners included the Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training Department of Training (DoT), the Regional Polytechnic Institute Techo Sen Siem Reap, the Provincial Training Centers (PTCs) in Tboung Khmum and Ratanakiri provinces, and Krousar Yoeung Association (KrY). Its goal, objectives and key results are outlined in Figure 3 below.

|

VDTYP GOAL |

|||

|

By 2017 the most disadvantaged out-of-school young people in Siem Reap, Kampong Cham / Tboung Khmum and Ratanakiri will have access to high quality and relevant vocational training that links them to dignified work opportunities |

|||

|

OBJECTIVES |

|||

|

Disadvantaged young women and men in targeted provinces have the supportive environment and equal opportunities to access quality vocational training and decent jobs |

High quality and relevant vocational training is provided to disadvantaged young women and men in targeted provinces |

Markets provide increased and dignified work opportunities and decent livelihoods for disadvantaged young women and men in targeted provinces |

National-level policy and institutions support the most disadvantaged / marginalized young women and men to access quality vocational training and decent work opportunities |

|

KEY RESULTS |

|||

|

Disadvantaged young people, parents, communities and local authorities value and support vocational training opportunities and help to provide these to disadvantaged out-of-school young women and men Disadvantaged out-of-school young women and men have the awareness, desire and necessary support to participate in vocational training |

Target training providers have the capacity to develop and deliver high quality, relevant training courses that respond to the needs of disadvantaged young women and men Vocational training courses are market oriented and prepare trainees for relevant work opportunities Disadvantaged young women and me are able to attend and successfully complete vocational training courses |

Disadvantaged young women and men are successfully engaged in self-employment through access to skilled micro-enterprise opportunities Employers provide equal opportunities for disadvantaged young women and men to access skilled work Training graduates have adequate support to ensure they successfully manage the transition into paid work or self-employment |

Project experience and networking with key stakeholders enables learning and clarification of project approaches among project partners Key policy issues and capacity building are identified, enabling national level engagement around vocational training and work for disadvantaged young women and men |

Figure 3: VTDYP Goal and Objectives

The final evaluation of the project confirmed its success in achieving its intended outcomes in terms of meeting enrolment targets and in gaining graduate employment, business creation or work readiness for those seeking employment (PLAN INTERNATIONAL 2017d).

Table 2: Trainee involvement in the VTCYP

|

Trainee involvement in the Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia Project |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

Target No. |

No. Male |

Male % |

No. Female |

Female % |

Overall Result |

No. Achieved |

||||||||

|

Youth involved in training (overall) |

1,816 |

722 |

39.9 |

1,038 |

57.35 |

met target |

1,810 |

||||||||

|

Graduate outcomes in the Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia Project |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total Graduates |

Total Grad-uates Gaining Employment |

% of Total Graduates gaining Employment |

No. Wage Employed |

% Wage Employed |

No. Self Employed |

% Self Employed |

No. Completed Internship |

% Completed Internship |

|||||||

|

1,810 |

1,069 |

59% |

569 |

31.4 |

500 |

27.6% |

659 |

36.4% |

|||||||

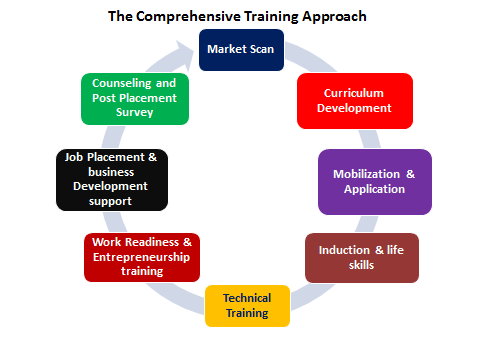

Factors responsible for the attainment of project objectives identified in the evaluation included internships, market-driven TVET courses, involvement of private sector in designing courses, flexible models of training (including enterprise-based training), specialized training for enterprise trainers working with young people with disabilities, direct job placement, free course arrangements (food, accommodation, medical fund for young people with disabilities), course choice for trainees, partnerships with – and capacity building of – R/PTCs, close collaboration and problem solving among partners, combining soft skills with technical skills, follow-up / coaching support after graduation and working with families to ensure an enabling environment (PLAN INTERNATIONAL 2017d, 5). Unintended positive outcomes of the project included improved health and hygiene of students, enhanced socialization, improved critical thinking, less reliance on parents and the improved reputation of trainees and graduates within their communities. The evaluation concluded that the project’s replicable tools and approaches included the market scan methodology, M&E system, soft skills component, planning processes, partnership development, enterprise-based training and job placement process. The VTDYP adopted a holistic, learner-focused approach to training (PLAN INTERNATIONAL 2017a, 8) as outlined in Figure 4 below.

3.2 Enterprise based Training

The enterprise-based approach was of particular value to the VTDYP. Trainees were provided with experiences and learning strategies to ensure the acquisition of conceptual, technical and generic skills and the transferability of skills to new contexts (Dawe 2002, 32). It provided trainees with a practical vocational experience of appropriate duration, expert support, relevant assessment processes, certification (Smith & Comyn 2003, 10) and pathways for continued learning (OEDC 2016, 6). It enabled trainees to learn practically through hands-on experience, built technical skills and improved confidence through working in a business and interacting with customers.

For Enterprise trainers / employers it reflected the needs of the local labour market, built PTC / employer relationships and provided meaningful incentives. It provided local businesses with employees and material support that stimulated local enterprise and economic development. Enterprises contributed to corporate social responsibility by helping disadvantaged young people (PLAN INTERNATIONAL 2017, 2).

Figure 4: The VTYP TVET Training Mode

Table 1: The VTYP TVET Training Mode

|

|

Step |

Description |

|

1 |

Market Scan |

Analysis of local markets and stakeholder surveys to inform training options and identify market demand. |

|

2 |

Curriculum Development |

Development of intended learning outcomes for technical, soft skills, work readiness and entrepreneurship training based on leaner focused methodologies. |

|

3 |

Mobilization & Application |

Awareness raising among potential trainees and their families regarding vocational training opportunities and issues of equality of opportunity in regards to gender, ethnicity and disability. |

|

4 |

Induction & Soft Skills |

Orientation and induction of trainees to raise awareness of opportunities build self-confidence and strengthen communication, interpersonal and literacy/numeracy skills. |

|

5 |

Technical Training |

Center-based, community-based and enterprise-based training options to enable training to respond to trainee needs and circumstances. |

|

6 |

Work Readiness & Entrepreneurial training |

Training to enable trainees to apply for and undertake formal employment and to assist trainees who intend to create their own micro or small businesses. |

|

7 |

Job placement & business development support |

Assist trainees to gain work experience or gain employment after graduation and to provide those who choose to establish their own business with advice and links with suppliers and microfinance options. |

|

8 |

Coaching & Follow up |

Monitoring of graduate experience in employment or enterprise development and to link this information with continuous improvement initiatives. |

3.3 Soft Skills Training

The holistic approach to skills development adopted by VTDYP included a structured 3 day program supported by real life experience in the workplace. The Soft Skills component of the VTDYP included:

− behaviours such as adaptability, resilience & customer-focus

− cognitive skills such as critical analysis, literacy & problem solving (Business Council of Australia 2016)

− “occupational capabilities” (Wheelahan, Buchanan & Yu 2015, 13) like the ability to act appropriately in a given situation, apply knowledge and think strategically

− appropriate attitudes, beliefs and values (Siekmann & Fowler 2017, 17)

− cognitive and socio-emotional skills.

Overall the Soft Skills component assisted trainees to develop the ‘adaptive capacities’ needed to respond to occupational and societal changes and to prepare them for future circumstances that cannot be predicted with any certainty. Specifically the Soft Skills program:

− delivered course content and duration consistently to enable the assessment of its impact across all locations

− served to enable trainees to engage in employment or start an enterprise

− maintained its currency, adaptability and value over the duration of the training program

− enabled trainee access to soft skills development in locations that suited them

− reflected local industry needs identified through initial discussions with local business owners

− extended and complimented generic skills being acquired within the work locations of enterprise based trainees

− supported the VTDYP “social inclusion” strategy and community partnership approach

− aligned with international soft skills and employability frameworks (World Bank 2014) as well as MoLVT strategic intentions for TVET.

4. Project Good Practices

The study identified 12 good practices across the pre-training, training and post training components of the VTDYP.

|

|

Good practice |

Examples of implementation |

|

PRE-TRAINING phase |

||

|

1. |

Thorough pre-course information |

Program pre-course information was timely, accurate and accessible to the target group. Inclusive eligibility criteria – ID Poor, disability and HIV status, ethnic minority and orphan status as well as family size were established. Information was disseminated within target communities about learning options, enterprise choices and program requirements through Commune Consultative Committees. Radio broadcasts, question and answer sessions as well as meetings with local authorities, parents and targeted disadvantaged young people were utilized. Attitudinal barriers and pre-determined beliefs about the involvement of young people with disabilities were addressed. |

|

2. |

Equitable trainee recruitment |

A broad recruitment base drew applicants from ethnic minorities, those with varying levels of education or with disabilities who were likely to be the most disadvantaged. Community Development Specialists (CDS), Job Placement Officers (JPO) and Krousar Yeoung (KrY), a domestic NGO, were engaged for counseling and family liaison, setting of realistic expectations and addressing parental concerns about welfare. Regional/Provincial Training Centers collaborated with industry in the identification of relevant technical and soft skills through a market scan to canvass potential areas for employment or business development. Center-based training or Enterprise-based training options were offered to trainees. Half day orientation sessions for center based trainees at their respective. Regional/Provincial Training Center and for enterprise based trainees at local districts halls were provided. A budget was earmarked to support program accessibility for trainees with disabilities. |

|

3. |

Industry involvement |

An industry scan was conducted prior to the program to identify local labour requirements. A pre-determined range of training options with high employment prospects was offered including motorbike and car repairs, sewing, beauty, electrical wiring and hairdressing. Experienced enterprise trainers were engaged in the orientation process. |

|

4. |

Manage-ment consistency |

Documentation was kept to a minimum and aligned with the literacy requirements of enterprises and trainees. PTCs maintained consistency in training implementation though document and process management, with one holding ISO 9001:2015 management system certification. |

|

TRAINING phase |

||

|

1. |

Relevant program model |

Course model/s, duration and environment suited the different learning needs of trainees. Courses were relatively short (generally 4-6 months with possible extension) with a focus on work readiness. The program focused on the informal economic sector where there is a need for skilled labour. Training for disabled trainees was individualized and flexible in terms of duration and location, particularly through the Enterprise training model. |

|

2. |

Practical curriculum |

Technical and soft skills were incorporated into the training program. Creativity and innovation were encouraged, especially in the sewing and beauty industries. Curriculum content was flexible in terms of delivery and content, and based predominantly on the personal experience and acquired knowledge of enterprise trainers. Community-based Enterprise Development (C-BED) training was provided for trainees intending to start a small business. |

|

3. |

Soft skills develop-ment |

Soft Skills training was provided to trainees at convenient locations by specialist Soft Skill trainers. A ministry approved training manual was utilized for course fundamentals and extended by trainers to suit the circumstances of individual trainee cohorts. |

|

4. |

Industry relevant training venues |

Enterprises to which trainees were to be assigned were screened prior to the commencement of the program and monitored over the duration of the program by JPO or CDS officers. Enterprise trainers were provided with incentives that included a payment of approximately $300 at the commencement of the program, enhanced reputation through corporate citizenship and increased staff numbers through trainee engagement. |

|

5- |

Experienced trainers |

Enterprise trainers with significant business experience and strong program commitment were recruited. |

|

6. |

Construc-tive feedback |

Trainee skill assessment was integrated into the training process and based on the observation of trainee practice and the provision of regular verbal feedback. |

|

7. |

Appropriate trainee services |

Most Enterprise trainees were accommodated with Enterprises trainers’ families, or in rented accommodation close by, thus mirroring the community environment from which they had come. Center-based trainees were accommodated either on campus or in rented accommodation. All trainees were covered by Trainee Self Health Insurance Policy in the event of sickness or accident. Counseling services were provided by throughout the training by KrY. JPO / CDS completed monitoring visits to Enterprise Trainees every 2-3 months, as well as phone contact with trainers and trainees. A Disability Inclusion Officer was appointed and disability was mainstreamed to enable trainees disadvantaged by disability to complete their training with their fellow students. |

|

POST TRAINING phase |

||

|

1. |

Graduate employment and work readiness |

Graduates who opened their own business had access to financial and material support. Small grants of $50-$300 to support business establishment were available through program funds and microfinance loans of $500-$800 were available to trainees through ILO sponsorship. Collaborative enterprises were established by some groups of graduates through the sharing of capital and skills. Graduate internships were available for a 2-3 month period with some private sector industries. All graduates were issued a MoLVT Vocational Certificate on completion of the program, with certificates providing credibility to graduates starting their own businesses and greater opportunities for graduates seeking employment. The achievements of outstanding graduates were showcased to local industry for possible employment. Some Center-based graduates enrolled in further training to seek higher level qualifications. CDS and JPO staff monitored those who had not gained employment or commenced their own business in order to provide further advice and support. |

Figure 1: Identified TVET Good Practices in the VTDYP

5. Discussions and Implications for Improvement

The role of industry in all phases of the training process – market scanning, competency development, the training process, trainee assessment and internship/employment – is recognized as indispensible for TVET systems. Training programs could be enhanced in the future with an increased involvement of individual enterprises and industry bodies. The enterprise model could provide a wider range of learning experiences that would support trainees’ introduction to their chosen industry. Enterprises engaging trainees need to understand and demonstrate industry “best practice” – in all aspects of their operations including safety, technology, customer support and operational management. All enterprises offering enterprise based training could, for example, hold at least minimal workplace safety national standards in their particular industry. Each PTC needs to know what best enterprise practice is in each industry and require (assist if necessary) enterprises to meet at least industry quality standards. Perhaps some kind of external assessment of a candidate’s skill level in soft skills could be valuable – to demonstrate minimal competences in this area.

The management system at the Regional Training Center at Siem Reap was certified to ISO 9001:2015 as a means of assuring minimum international standards were being maintained within its internal management systems, and to support its marketing strategy by assuring potential graduates and their families that quality was at the heart of its operations. The benefits of holding this standard, which is re-confirmed on an annual basis by external, authorised certification body, was that accurate and comprehensive documentation existed for all aspects of course provision. This system enabled the thorough monitoring of all aspects of trainee engagement with the RTC and also served as the basis for the continuous improvement of the management system. This level of certification would be a valuable step for all R/PTCs as a means of enhancing documentation and management system quality.

The education of many trainees was limited due to the fact that they had dropped out of school at primary school level. This left a significant gap in their educational experience and a potential barrier to their full participation in the training program. Seen as a process rather than an event, trainee orientation could provide the opportunity to assess the educational status and needs of new trainees in terms of, for example, literacy and numeracy, their ability to interact with others, and to construct a broader educational curriculum to complement the technical skills training being undertaken. Identifying and addressing the barriers that may prevent, or limit, equal access to training opportunities is an on-going challenge. Such barriers may be associated with family attitudes, disability, cultural expectations, community pressure or the effects of previous experiences. The following up of trainees who withdraw from the program is an important step that could be strengthened in order to identify and address barriers to participation. Some sewing and salon graduates, for example, did not gain employment because of family pressure to work at home, marriage, migration or difficulties in starting their own business. These issues could be investigated further to ascertain the degree which they are barriers to youth education and training.

In some enterprises trainees were given the opportunity to be creative and innovative by enabling them to experience the range of work situations within their chosen industry. This could be more widely adopted as a learning process so that trainees gain an “industry wide” perspective to complement the “enterprise perspective” that they were developing. It is important that trainees gain a depth of experience when undertaking their training. The opportunity for trainees to gain that experience varied across the enterprises observed during the study. If common industry competences were identified, trainees in the same industry but in different enterprise locations could achieve similar learning outcomes. This would also serve the purpose of providing the trainees and enterprise trainers with a goal to aspire to by the completion of the training. The integration of soft skills (work readiness and employability skills) into the training, particularly communication skills, and the opportunity to practice these skills, may require these skills to be more explicitly modeled throughout the program by center-based and enterprise-based trainers. There is a need for similar training programs to enhance disability inclusion through:

− “reasonable adjustments” that enable full and equitable trainee participation, such as changes to the work environment that allow people with disability to work safely and productively

− challenging preconceptions that paid employment is not a viable option for young people with a disability

− closely monitoring welfare and child protection for enterprise-based trainees, especially female trainees

− the encouragement of a broader choice in occupation options that would challenge traditional beliefs about gender domination

− compiling comprehensive data on barriers that, along with impairment, may be preventing the involvement of young people with disabilities

− ensuring the appropriate confidentiality in relation to disability status

− an enhanced use of technology and networking for awareness raising and education about training outcomes for young people with disabilities.

Trainees living in accommodation at a separate location from the Enterprise trainer may require extra supervision. Soft skills training for trainees under 18 years, those with disabilities or those who have less formal education may need to include assertiveness or other similar training that equips them to manage a range of unfamiliar social and employment situations. An understanding of, and commitment to, PLAN INTERNATIONAL’s child protection policy is particularly important for young people (particularly women) under the age of 18 years, and those with an identified disability, who are undertaking enterprise based training. Mandatory refresher courses and re-confirmation of commitment to child protection, welfare and safety by enterprise trainers may serve to minimize risk to trainees.

Opportunities to bring graduates in similar circumstances together to share successes and challenges could promote the sharing of good business practices and serve to encourage continuous improvement and business sustainability. Post-graduate support is a key element of training programs. It was clear that some graduates, especially those commencing their own businesses, were experienced varied degrees of difficulty. Those with strong family support, especially technical and financial support, were more confident and seemingly more successful than those who lacked such assistance. Advice, certification, equipment and funding need to be available to each graduate on an equitable basis.

6. Conclusion

The ongoing quest for quality in its various forms is an important challenge for TVET. The VTDYP was a quality program in many ways. It was based on a model that reflected the complexities of working with disadvantaged young people, their families and communities. It responded to their need for employment – to earn a living and to build a future. For many students whose formal education had been cut short it was more than a skills training program – it was an educational experience. They learned how to communicate, to think and plan – to make decisions, take responsibility – and they experienced different perspectives to life. For many trainees it was – in their words – a “life changing” experience that had “changed everything”! Enterprise trainers also praised the program for its capacity to meet their industry requirements and to energize their enterprises. The highly practical nature of the program suited their approach to business and their systems of training and assessment.

The 12 good practices identified and discussed in this paper reflect the pre-training, training and post training phases of the program and confirmed the success of the enterprise based learning model and accompanying soft skills program as one that led to the achievement of intended project outcomes. The collaborative, interagency approach at the heart of the project involving government, NGOs, the private sector and communities developed mutual trust, encouraged interdependency and facilitated shared learning. It is hoped that the good practices presented in this paper, and the improvements suggested, will encourage dialogue and promote further innovation relating to the role of TVET in local economic development and poverty alleviation for young people in Cambodia.

References

ADB (2009). Good Practice in Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Manilla, Philippines: ADB.

ADB (2016). Policy priorities for a more responsive Technical and Vocational Education and Training System in Cambodia: Policy Brief No. 73. Manilla, Philippines: ADB.

Axmann, M., Rhoades, A., & Nordstrum, L. (2015). Vocational teachers and trainers in a changing world: the imperative of high quality teacher training systems. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO Employment Policy Department.

Business Council of Australia (2016). Being Work Ready: A guide to what employers want. Melbourne: BCA.

CDRI (2015). Final Report on Desktop Study on Non-formal education in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: CCRC.

Choy, S., et. al. (2008). Effective Models of employment-based training. Adelaide: NCVER.

Dawe, S. (2002). Focusing in generic skills in training packages, Adelaide. SA: NCVER.

Griffin, T. (2017). Are we all speaking the same language? Understanding “quality” in the VET sector. Adelaide: NCVER.

Khien, S., Madhur, S., & Chhem, R. (eds.). (2015). Cambodia Education 2015: Employment and Empowerment. Phnom Penh: CDRI.

OECD (2016). Bridging the Gap – The Private Sector’s Role in Skills Development and Employment: 4th Regional Dialogue on TVET, OECD Southeast Asia Regional Policy Network on Education and Skills. Cebu City, Philippines: OECD.

OECD Development Centre (2017). Youth Well-being Policy Review of Cambodia, Paris: EU-OECD Youth Inclusion Project.

Paryono (2017). The importance of TVET and its contribution to sustainable development. Brunei: SEAMEO VOCTECH Regional Centre.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2013). Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People Cambodia: Project Proposal Document. Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL Cambodia.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2014). Trainee’s Self Health Insurance Policy. Phnom Penh: PLAN International.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2016). Management Response on Review of Disability Inclusions. Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2017a). Annual Narrative Report: Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2017b). Project Implementation and Management: Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: PLAN International.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2017c). Project Completion Report: Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL, (2017d). Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Young People in Cambodia Project, Final External Evaluation. Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL.

PLAN INTERNATIONAL (2016). Guideline on Disability Inclusion for Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Out of School Youth Project (Version 6). Phnom Penh: PLAN INTERNATIONAL.

Richter, S. (2013). Final Report: Youth Vocational Training and Employment Project. Box Hill Victoria: Box Hill Institute.

RGC (2009). Law on the Protection and the Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Phnom Penh: MoSVY.

RGC (2014). National Disability Strategic Plan 2014-2018. Phnom Penh: Disability Action Council.

SEARPN (2015). The 7th Annual Expert Meeting of the Initiative on Employment and Skills Strategies in Southeast Asia (ESSSA) and the 2nd Regional Policy Dialogue in TVET Personnel. Siem Reap, Cambodia: SEARPN.

Siekmann, G., Fowler, C. (2017). Identifying work skills: International approaches. Adelaide, South Australia: NCVER.

Smith, E., Comyn, P. (2003). The Development of Employability Skills in Novice Workers. Adelaide: NCVER.

Smith, J. (2016). Review of disability inclusion in PLAN Cambodia’s Vocational Training for Disadvantaged Youth in Cambodia project. Box Hill, Victoria: CMB Australia.

UN (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). New York: United Nations.

UNESCO (2016). Strategy for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) 2016-2021. Paris: UNESCO.

Walther, A., Pohl, A. (2005). Thematic Study on Policy Measures concerning Disadvantaged Youth. Study commissioned by the European Commission, DG Employment and Social Affairs in the framework of the Community Action Programme to Combat Social Exclusion. Tubingen: Institute for Regional Innovation and Social Research (IRIS).

World Bank (2014). Strengthening Life Skills for Youth: A practical guide to quality programs. Baltimore, USA: International Youth Foundation.

Citation

Berry, G., Sovann, S. & Leng, M. (2018). Good Practices in TVET for disadvantaged young people in rural Cambodia. In: TVET@Asia, issue 11, 1-16. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue11/berry_etal_tvet11.pdf (retrieved 30.06.2018)