Abstract

This article is based on research and detailed empirical work that has been conducted in Australia in the area of transferable skills. The article will review the issues related to transferable skills in the vocational education and training (VET) sector from a historical perspective. Included in the discussion are details of recent and current policy development. A commentary is provided on many of the challenges of policy implementation in the current environment. There has been considerable research into this issue in Australia, and it is hoped that this article will assist in a broader understanding of the issues surrounding transferable skills.

1 Introduction

In Australia, the discussion about transferable skills has been taking place for a number of years in all educational sectors. There have been a number of high level reviews and extensive consultations with industry and other VET stakeholders. Currently, transferable skills are referred to as employability skills[1] . However they are also now located within a broader category of skills referred to as foundation skills that describe a combination of language, literacy and numeracy skills and other skills required to engage successfully in vocational activities. It is acknowledged that these skills are manifested differently depending on technical and discipline-specific context. The details of research identifying this manifestation will be discussed in more detail.

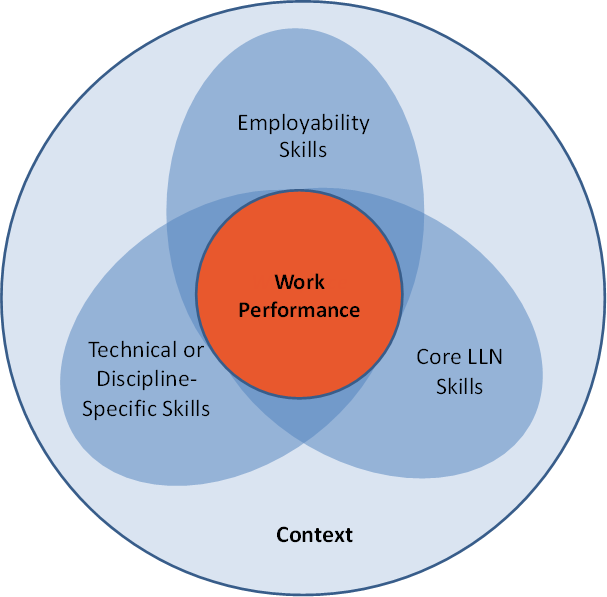

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Core Skills for Work (CSfW) Framework[2] (previously Employability Skills Framework) outlines three sets of inter-related skills (employability skills, technical or discipline specific skills and core language, literacy and numeracy skills), as well as a range of features, expectations and requirements of the surrounding context, which contribute to work performance. Examples of context include the level of qualification, the type of work (supervisory, strategic or operational), licensing requirements of the industry, industry culture, industrial relation laws and enterprise requirements. CSfW encompasses both employability skills and aspects of the context which impact upon an individual’s ability to develop and demonstrate these skills. Technical or discipline specific skills are detailed in Training Packages and school and higher education curricula, while the core language, literacy and numeracy (LLN) skills of reading, writing, oral communication, numeracy and learning are addressed in the Australian Core Skills Framework. (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR), 2012, 4).

Figure 1: Employability Skills in context (DEEWR, 2012, 5

It is very much the case that the topic of transferable skills is located in a complex environment of sometimes competing policy initiatives. Some examples of these complex policy factors are the interests of industry bodies, funding bodies, VET practitioners and students. It is also the case that there are inherent tensions in the VET system between technical expertise and transferable skill development that mitigates against a clear understanding of what transferable skills actually are and how they are to be taught, assessed and reported.

2 The concept of transferable skills in VET and vocational teacher[3] education (VTE) policies

2.1 Australia’s national policy on VTE

Teachers and trainers working in the VET system in Australia who deliver nationally accredited training must have as a minimum qualification Certificate IV in Training and Assessment (TAE4110 2012). As is the case with all qualifications in the VET system, this qualification includes a list of the employability skills graduates will demonstrate, and a list of the industry/ enterprise requirements. These are in addition to a set of competencies that focus on the technical vocational aspects of the qualification.

All these requirements are defined in a related training package[4] , including the explicit description of the employability skills. Whilst these skills are mandated in this training package, there is a lot of discussion about the effectiveness of the embedding process and the quality of the teaching and assessing of the employability skills. There is also a lot of discussion about the extent to which teachers and trainers are adequately prepared to deal with this complex topic and how effectively the process of embedding these skills is carried out. It is also contingent on how clearly and concisely these skills are written into the respective training packages. Future policy initiatives will have to address these well-documented and researched issues.

The question that follows from the VTE policy that mandates the minimum qualification for VET practitioners in Australia is: Does this policy emphasise the importance of enhancing the development of transferable skills through VET practitioner education programs? An investigation shows that only one very small item of emphasis can be found in the Certificate IV in Training and Assessment. The compulsory components of this qualification include ten units of competencies, of which only one, Provide Work Skills Instruction, gives any such emphasis. A graduate of this unit must be able to Use measures to ensure learners are acquiring and can use technical and generic skills[5] and knowledge. (Australian Government, 2013). Perhaps it is not surprising then, that research in Australia has identified a general dissatisfaction on the part of many stakeholders with the standard of professional development of VET practitioners in this area.

In research conducted in 2003, Clayton et alfound that despite the general consensus that transferable skills are valuable, practitioners are unclear as to how they should be assessed. Other findings show that VET practitioners also require further professional development support in order that their own skills, knowledge and abilities are sufficient to enable them to deliver and assess transferable skills.

In more recent research conducted by the Commonwealth of Australia in 2012, it was found that industry bodies who advocated the need for significant reform raised a variety of concerns including an improved capability of VET practitioners (Commonwealth of Australia, 2012(a)).

Whilst the regulated national standard is established at the Certificate IV level, a number of diploma and bachelor degree level programs are also offered in Australia for VET practitioners. The place these qualifications hold in terms of the Australian Qualifications Framework can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Australian Qualifications Framework

(Source: Australian Qualifications Framework Council, 2013. Australian Qualifications Framework, 2nd edition, January 2013)

The diploma and bachelor qualifications are generally offered with advanced standing for entrants’ existing vocational skills and qualifications. Therefore, the programs are generally shorter in length than those in other sectors of education such as lower primary, middle and secondary schools. An analysis of the content of three such bachelor degrees across Australia shows that two make some reference to graduates developing the ability to teach and/or assess transferable skills. The first of these two makes explicit reference to the development of knowledge by incorporating performative learning, situational learning, problem-based learning and workplace learning; (Charles Sturt University, 2011a) and one learning outcome of Using the Core Skills Framework (Charles Sturt University 2014b).

The second bachelor degree identified includes subjects entitled Literacy at Work (Griffith University, 2013a) and Lifelong Learning and Work (Griffith University, 2013b). Whilst these could be seen as aligning with some transferable skills, no specific reference to any of the transferable skills frameworks existing in Australia are made. In addition, there are references that could be construed as developing VET practitioners’ ability to teach and assess transferable skills. For example, graduates must be able to demonstrate an understanding of the significance of the need for alignment of the intent, enactments and outcomes of contemporary educational issues and initiatives in adult and vocational education (Griffith University, 2013b). Transferable skills in the form of the variety of frameworks identified in Australia, for example the Core Skills Framework, may fit well within these parameters.

To conclude, the evidence shows a lack of explicit reference to transferable skills as an area for VET practitioner development. It is reasonable to say that Australia does not emphasise the importance of teacher training including pedagogical skills necessary for enhancing the development of transferable skills.

2.2 Practical vocational skills held by VET trainers and assessors

The Australian Vocational Education and Training Quality Framework (VQF) was created through legislation and it includes standards for employment as a vocational trainer and assessor. The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) (2013) states that in order to meet these standards a person must have the relevant vocational competencies at least to the level being delivered or assessed and demonstrate current industry skills directly relevant to the training/assessment being undertaken.

This ensures that VET practitioners must hold practical vocational skills through experiences gained in the world of work. This is a very important, and strongly regulated, feature of VET in Australia. It is likely to be strengthened in future VET developments.

The most commonly used instrument for teaching and assessing in VET is a training package related to a specific industry area. The Construction and Property Services Industry Skills Council in Australia states that people who are considered eligible to deliver and assess qualifications from the construction, plumbing and services training package, must have the following minimum competency, recognition and experience:

- formal recognition of competency at least to the level being assessed;

- relevant industry experience, that is, workplace experience within the last two years in the competency area being delivered;

- relevant occupational registration or licensing in areas where this is a regulatory requirement (Australian Government, 2012).

Although this requirement has been established, research indicates that there is some dissatisfaction with its implementation. It is unclear to what extent the industry currency of trainers and assessors is a factor in this dissatisfaction, though it is understood to be a factor (Commonwealth of Australia, 2012).

The fact that VET practitioners are dual professionals (ASQA, 2013) presents a significant challenge. They must hold their industrial currency and qualification, as well as training and assessing currency and qualification. There are issues concerning who is responsible to ensure that these requirements are met. Some are of the opinion that the individual VET practitioner has the responsibility, whilst others consider that the employing body has the responsibility to facilitate this requirement. In this zone of unclear delineation of responsibility it is often the case that this requirement is overlooked or ignored.

The VQF regulatory framework addresses this dilemma to some extent. The requirement to demonstrate that practitioners continue to develop their VET knowledge and skills as well as their industry currency is embedded in the standards. It is clear that ensuring that the ‘dual professionalism’ can be demonstrated is the legal responsibility of the educational institution offering qualifications. It is expected that this aspect of the framework will be strengthened in future versions.

A requirement for continued professional development is a feature of many industries in Australia, such as plumbing and electrical services. Although there is currently no stipulation of volume or type of such development in VET, there is the need to demonstrate that it is continually undertaken. There is considerable contested discussion on whether a benchmark for professional development should be set for VET trainers and assessors (Guthrie, 2010). A number of professional associations exist in Australia for VET practitioners. Membership of these is voluntary and generally not aligned to employment requirements.

Clayton et al (2003) made an important recommendation in their research. They found that not only business and industry, but also the entire Australian community will benefit if transferable skills can be successfully foregrounded in VET. However, substantial investment in the professional development of Australian VET practitioners is a necessary pre-condition for this achievement (Clayton, et al 2003). This recommendation remains true as an aspiration for VET in Australia in 2014.

2.3 Level of implementation of transferable skills

As mentioned earlier, transferable skills have played a significant role in the recent history of Australian VET. The subject of transferable skills featured in key reports that helped to shape Australian VET, in particular the Finn (AEC 1991), Carmichael (1992) and Mayer (AEC/ MOVEET 1992) reports. Key competencies “for effective participation in emerging forms of work and work organisation” (AEC/MOVEET 1992) were supposed to be developed alongside technical or vocational skills in Australia’s competency-based VET system. In 2002, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) and the Business Council of Australia proposed an Employability Skills Framework (Core Skills for Work Framework since 2013) to replace the key competencies. Eight skills are identified in the framework: (1) communication, (2) teamwork, (3) problem-solving, (4) initiative and enterprise, (5) planning and organising, (6) self-management, (7) learning; and (8) technology.

In 2005, the National Quality Council (NQC) endorsed the replacement of key competencies by employability skills in VET. Since that time more work has been done on transferable skills frameworks in the schooling and higher education sectors as well as in VET. Transferable skills relevant to VET appear in the Australian Core Skills Framework, which has a literacy and numeracy focus, while the Australian Qualifications Framework, which applies to qualifications in both the VET and higher education sectors, includes transferable skills.

Although the concept of transferable skills has been welcomed by most VET stakeholders, a number of problems relating to implementation have become apparent after nearly two decades of transferable skills development, assessment and reporting. A report by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2012) identified concerns with the current approach to transferable skills, including:

- differing definitions, interpretations and approaches used across sectors, and even within sectors, which create confusion about expectations;

- failure to recognise the context-dependent nature of employability skills and impact of the context upon these skills;

- incorrect assumptions that competence is automatically transferable;

- lack of explicit focus on employability skills in workplaces and in education and training

- insufficient confidence and/or capability of teachers and trainers to address these skills

- the difficulty of measuring, assessing and reporting on employability skills. (DEEWR 2012, 5-6).

The Employability Skills Framework (DEEWR, 2012) seeks to address these issues. It stresses explicitness in relation to employability skills and envisages achieving this overarching goal in four ways. Firstly, developers of training packages, curriculum and programs will be encouraged to “clearly articulate the employability skills required for certain occupations or careers or at particular points in careers development” (2012, 14). Secondly, trainers and teachers will be expected to “more explicitly address the development of these skills in learners” (2012, 14). Thirdly, individuals should be in a position to articulate the employability skills they possess and those they would like to develop. Finally, the framework provides a common reference point for developers of education, training and employment services and products.

The first and second of these strategies highlight particular challenges in implementing transferable skills in Australian VET. While the importance of employability skills and the need for their development has been recognised by stakeholders, training packages have not explicitly identified the transferable components alongside the vocational or technical skills. Rather, specification of vocational skills and knowledge was supposed to embed employability skills so that the development of vocational skills automatically entailed acquisition of employability skills. Units of competency contained a component entitled Employability Skills Information and for all units the information was the same: This unit contains employability skills. This limited guidance has had consequences for the level of implementation of transferable skills in Australia.

The National Skills Standards Council (NSSC) guidelines for the development of training packages introduced in 2012 addressed the goal of making employability skills explicit. According to these guidelines, units of competency must now contain a section on foundation skills (language, literacy, numeracy and employability skills). This policy document states that training package developers must ensure that foundation skills are explicit and recognisable within the training package (Commonwealth of Australia, 2012). These requirements are expressed within the foundation skills field of the unit of competency template. Training packages reflecting these guidelines are currently being phased in.

The second strategy for addressing transferable skill development concerns the role of trainers and educators. These practitioners generally base their work on translating the requirements of training packages into training programs and assessments. While these transferable skills have not been specified in training packages in the past in Australia it was unlikely practitioners would place a lot of emphasis on transferable skills, particularly in an environment where commercial pressures are on providers to teach no more than what is explicitly set out in the training packages.

The Australian government and other stakeholders have been aware that practitioners require support to address employability skills development. Resources for trainers and assessors such as the Department of Education, Science and Training’s (DEST) Employability Skills: From Framework to Practice (2006) set out principles that practitioners can use to promote the development of employability skills. According to this resource, certain pedagogical approaches foster specific employability skills (see Table 1).

Table 1: Learning approaches and employability skills

|

Approach |

Explanation |

Employability skill(s) developed |

|

Responsible learning |

Responsible learning encourages learners to take ownership of the learning process through more direct and active participation in the learning process and includes the following: making meaning out of new knowledge, distilling principles which will aid transference to new contexts and practicing skills and mastering processes. |

|

|

Experiential learning Authentic learning |

Experiential learning emphasises ‘learning to do’ and ‘learning from doing’. Authentic learning occurs when learners have an opportunity to apply their skills and knowledge in authentic work environments or in contexts which attempt to simulate the real. |

|

|

Cooperative learning |

Cooperative learning encourages learners to learn from each other, share learning tasks and learn from a range of people including colleagues, mentors, coaches, supervisors, trainers, and others. |

|

|

Reflective learning |

Reflective learning is about consciously and systematically appraising experience to turn it into lessons for the future. This can be introspective, where learners are encouraged to examine changes in their own perceptions, goals, confidences and motivations. It addresses: developing critical thinking skills, learning to learn and developing attitudes that promote lifelong learning. |

|

Source: Adapted from DEST (2006), 46-47.

It is interesting to note that this kind of specific pedagogical advice is not included in the Certificate IV in Training and Assessment, the mandated minimum qualification for VET teachers in Australia.

3 Implications for policy and practice

Australia had a change of government on 7th September 2013 and the following possible policy directions and associated practices must be understood within this context.

In regard to transferable skills in VET, there was an overarching policy commitment through the 10-year National Foundation Skills Strategy building around a shared vision for a productive and inclusive Australia. This Strategy had been developed over a number of years and it is useful to articulate its dimensions as it may be used to inform the policy directions of the current new government. In this Strategy, foundation skills are defined as the combination of English language, literacy and numeracy (LLN) – listening, speaking, reading, writing, digital literacy and use of mathematical ideas; and employability skills, such as collaboration, problem solving, self-management, learning and information and communication technology (ICT) skills required for participation in modern workplaces and contemporary life.

Foundation skills development includes both skills acquisition and the critical application of these skills in multiple environments for multiple purposes. Foundation skills are fundamental to participation in the workplace, the community and adult education and training. (Standing Committee on Tertiary Education, Skills and Employment, 2102, 2)

The Strategy came with a large number of suggested policy actions and practice implications that were then circulated for consultation. It remains to be seen which if any of these policy recommendations will be adopted by the new government. The previous government devoted a lot of time, attention and consultation space to the topic of employability skills.

As part of this policy commitment a high level committee was formed to supervise phase 1 of the employability skills project. The then government was committed to funding the development of a new framework that was to be called the Core Skills for Employment Framework. The consulting group Ithica produced its final report in January 2012: Employability Skills Framework – Stage 1: Final Report (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, 2012). This report was based on extensive consultations with approximately 700 people and groups across Australia.

“Based on extensive consultation carried out in this first stage of the Framework development, we recommend that the Framework focus specifically on ‘the non-technical skills and knowledge necessary for effective participation in the workforce’ (i.e. employability skills), as distinct from those required more broadly in society. Participation in the workforce could be as an employee, an employer, as a self-employed worker, or a volunteer.” (DEEWR, 2012, 4).

The Committee advising the government made six recommendations[6]which focus specifically on non-technical skills and knowledge to equip people for participation in the world of work; the need for an agreed language around employability skills and the framework; the importance of having a developmental framework and not a static one; and the fact that the framework should not be job specific. These recommendations have not yet been translated into policy action and it is not certain how the new government will react to these. However, there has been persistent and ongoing interest in the concept of employability skills and their importance for the development of qualities such as innovation, productivity and creativity beyond the exigencies of day-to-day work.

For that reason, very training package in Australia contains a section on employability skills and it is the expectation that teachers and trainers will embed these in their teaching and assessment practices. Every training package contains an employability skills summary for each qualification issued in Australia. Training packages are mandatory and therefore employability skills are seen as a necessary component of teaching, training, assessing and reporting.

4 Key findings

In this uncharted and complex policy area a number of issues remain clear irrespective of political persuasions.

The key findings from this study are:

- Employability skills are regarded by all parties as crucial for the increasing productivity and profitability of the Australian economy;

- The concept of transferable skills is and has been enthusiastically embraced by the VET sector in Australia;

- There is a policy commitment to create circumstances under which these transferable skills can be taught, assessed and reported;

- All sectors of the country agree on the importance of these skills and the role they play in building productivity and international competitiveness;

- There is a lot of interest and encouragement for the development of transferable skills coming from industry. Prominent business and industry groups have suggested that employability skills need to be more explicitly taught, assessed and reported;

- Given that employability skills are sometimes best learnt on the job, there is a potential new role for employers in the development of these skills;

- All Training Packages in Australia have transferable skills embedded into them. Therefore, the policy expectation is that teachers will teach, assess and report on them as part of the student’s results on completion of an individual unit within the qualification being studied;

- There is no common language for discussing the concepts underlying employability skills and the debate is often very fuzzy;

- There is little teacher preparation or professional development concerning transferable skills, and a number of reports have explicitly identified the fact that the whole process is stalled at the point of implementation;

- VET teachers are technical experts in their own discipline areas and are not always well prepared to interpret associated transferable skills and to implement teaching strategies that ensure the development of these skills in their students;

- There is an inherent tension in the VET system between the highly specified and tangible articulation of the skills to be learnt in a technical area and the intangible and difficult to specify and identify transferable skills;

- Transferable skills are context specific and each industry area requires a different mix of these skills. This adds to the complexity and sometimes creates confusion in the minds of the VET teachers.

5 Conclusion

The importance of, and commitment to, the development of transferable skills in VET have been endorsed by the majority of stakeholders in Australia. Research conducted over a number of decades has informed Australia’s current position. Further research in this area will continue to inform and enrich the debate in regard to policy and practice.

In order to gain the most benefit globally from this research, the need for trans-regional and intra-regional collaborations are essential. Australia looks forward to continuing to be a part of the Regional Cooperation Platform (RCP)[7] investing effort in this aspect of VET. The possible benefits of this contribution, not only to business and industry, but also the entire regional community, will be significant.

References

Australian Education Council/Ministers of Vocational Education, Employment and Training (1992). Putting general education together (The Mayer report). Canberra, AGPS.

Australian Education Council Review Committee (1991). Young people’s participation in post-compulsory education and training: report of the AEC Review Committee. Canberra, AGPS.

Australian Government (2012). CPC08 – Construction, Plumbing and Services Training Package (Release 8.0). Online: http://training.gov.au/Training/Details/CPC08 (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Australian Government (n.d.). TAEDL301A Certificate IV in Training and Assessment. Online: http://training.gov.au/Training/Details/TAEDEL301A (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Australian Skills Quality Authority (2013). National VET regulations, VET Quality Framework. Online: http://www.asqa.gov.au/about-asqa/national-vet-regulation/vet-quality-framework.html (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Charles Sturt University. 2011. Handbook EEL320 Learning Theories for Post Compulsory Education. Online: http://www.csu.edu.au/handbook/handbook11/subjects/EEL320.html (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Charles Sturt University (2014). Handbook EPT327 Effective Teaching in VET. Online: http://www.csu.edu.au/handbook/subjects/EPT327.html (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Clayton, B.; Blom K.; Meyers, D., & Bateman, A. (2003). Assessing and Certifying Generic Skills. What is happening in vocational education and training? Australian National Training Authority, Australia.

Commonwealth of Australia (2012a). National Skills Standards Council Review of the standards for the regulation of vocational education and training analysis of submissions. Canberra: AGPS

Commonwealth of Australia (2012b).Standards for NVR Registered Training Organisations 2012. http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Series/F2013L00167 (retrieved 14.09.2013).

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) (2012) (retrieved 14.09.2013).. Employability Skills Framework, Stage 1 Final Report. Australian Government: Canberra.

Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST) (20006). Employability skills from framework to practice. Commonwealth of Australia.

Griffith University (2013). Griffith Portal Course profile(retrieved 14.09.2013).s, Literacy at Work. 3015EDN – Sem 1 2013 – Mt Gravatt Campus – Mixed Mode. Online: https://courseprofile.secure.griffith.edu.au/student_section_loader.php?section=2&profileId=70256(retrieved 14.09.2013).

http://www.innovation.gov.au/skills/CoreSkillsForWorkFramework/Documents/CSWF-Framework.pdf

[1]In this article, transferable skills and employability skills are used interchangeably.

[2]For more information, please go to: http://www.innovation.gov.au/skills/CoreSkillsForWorkFramework/Documents/CSWF-Framework.pdf

[3]Please note that in Australia the role of vocational teacher is generally known as VET practitioner.

[4]For more details on this training package, please go to: http://training.gov.au/Training/Details/TAE40110

[5]Generic skills is another term used to refer to transferable skills.

[6] Details of the recommendations can be found here

http://foi.deewr.gov.au/documents/employability-skills-framework-stage-1-final-report

[7] RCP is a network of universities involved in vocational teacher education (VTE) in the ASEAN region and China. Founded in 2009, at the present the platform focuses on VTE and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in the region through the exchange of experiences, the development of programmes and common research projects.

Citation

Brennan Kemmis, R., Hodge, S., & Bowden, A. (2014). Transferable skills in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET): Implications for TVET teacher policies in Australia. In: TVET@Asia, issue 3, 1-13. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue3/brennan-kemmis_etal_tvet3.pdf (retrieved 30.06.2014).