Abstract

This study focuses on how the Post School Education and Training (PSET) policy and development framework influences effectiveness and efficiency. In this research, we set out to better understand the experiences of the TVET college principals as managers of these institutions. The problem of low throughput rates by TVET colleges over the years has resulted in the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) not achieving the goals specified in policies. The study notes that the targets set in the National Development Plan 2030 (NDP 2030) and White Paper for Post School Education and Training (PSET) are not being achieved. This, in turn, raises questions about the performance of principals as managers of these institutions. “What factors affect the success of management in TVET colleges in the Gauteng province of South Africa?”. Various capabilities for managing and implementing change and achieving success have been proposed by policy and plans as cited above. However, TVET colleges in Gauteng continue to record low throughput rates. The researchers observed the lack of identified and associated guidelines formulated and enforced by the DHET, the college councils, and the management of TVET colleges to direct institutional goals. This suggests the absence of viable determinants of management success in these institutions. This paper investigates the lack of determinants of management success in TVET colleges. The qualitative research methodology examined the respondents’ opinions, behaviours and experiences. A suggested improvement model was presented. Given the limitations of the study, areas for further research are recommended.

Keywords: Determinants of success, performance, affect, management, factors.

1 Introduction

This study sought to explore factors that affect the management success in Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges in the Gauteng province of South Africa and understand the content and context of the problem. This paper thus reports on the factors that determine management success at TVET colleges and the lack of dedicated research to prove or disprove these factors in these institutions.

According to the United Nations Organisation for Science, Education and Culture (UNESCO 2021) TVET is regarded as a value-added portion of education that integrates technology, sciences, practical skills, attitudes, understanding and information relating to employment in different sectors of the economy and society. In South Africa, TVET colleges are considered a crucial investment sector in developing the country’s ability to address unemployment problems and boost economic development. However, TVET colleges notably face challenges by not responding to the ever-changing skills demands in the economy, which requires these institutions’ graduates to pass skills and knowledge appropriate for the workplace (Van der Bijl & Taylor,2016). Two critical elements need attention: the need for the TVET college principals to adapt to continuous change at the individual (occupational) and organisational levels. Notwithstanding the above, factors that determine management success indicate that the principals’ distinct combinations of attributes are key to success or failure. However, these capabilities cannot solely originate from a single person (principal/manager. The low throughput rates by TVET colleges over the years (see Table 1) have led to the DHET not achieving the specified goals. The National Development Plan 2030 states that the throughput rate indicates the performance of the TVET college system as per the targets set in the DHET plans (National Planning Commission 2013). Low throughput rates indicate the challenges TVET colleges face and call for performance improvement (see table below).

Table 1: Throughput rate of NC(V) Level 2 students 2016-2018

| Number of students enrolled NCV* Level 2 in 2016 | Number of students who completed NCV Level 4 in 2018 | Throughput rate (%) |

| 88771 | 8135 | 9.2 |

(Sources: DHET 2016; DHET 2018)

*National Certificate Vocational

The above table shows that, in the 2016 academic year, 88771 TVET college students enrolled for the NCV level 2 programme. In 2018, only 8135 students of this cohort completed the NCV 4. This implies that 9.2% of all students enrolled in the NCV level 2 programme in 2016 completed this qualification within the expected time frame. This low throughput rate is at variance to the target of 75% set by the NDP 2030 (National Planning Commission 2013). Thus, this paper aims to determine how principals deal with challenges faced in practice at TVET colleges and which factors prevent success.

The researchers observed that the targets outlined in the DHET plans, which need to be translated into operational plans at TVET colleges, are not being achieved. The targets are articulated in both the National Development Plan 2030 (National Planning Commission 2013) and White Paper for Post School Education and Training (DHET 2013). In management terms, this raises questions about the performance of principals as managers of these institutions. Consequently, this paper seeks to investigate “Factors that affect the success of management in TVET colleges in the Gauteng province of South Africa”. As stated above, the Act is evident in what needs to be done to restructure and transform TVET colleges into vehicles to deliver skilled citizens. In essence, TVET policy implementation is meant to create a link between demand (labour) and supply (education) by providing a framework within which TVET college programmes respond to labour market needs.

1.1 Population and Sampling

The research for this study was conducted at TVET Colleges in the province of Gauteng. South Africa has 50 TVET colleges across the nine provinces, which constitutes the study population. According to McMillan and Schumacher (2010), the research population denotes a group of elements or cases, objects, events or individuals that match specific criteria to which the study intends to generalise the results. In research, the population refers to the entire collection of individuals who need to be considered by the research. Sampling refers to the process of selecting units from the population of interest upon which the study can generalise (Trochim & Donelly 2006). According to Brink et al. (2006), qualitative sampling requires selecting appropriate participants to achieve the study’s objectives. Various sampling techniques are noted, including random sampling, purposive sampling, probability, systematic, and convenience sampling, among others (Creswell 2014). The purposive sampling method required the researchers to write to the Director General at the DHET to request permission to undertake the study and, thereafter, approach individual TVET college principals to gain their approval for the research. Table 2 shows the description and profile of the participants involved below.

Table 2: Description and profile of participants

| Code | Gender | Qualifications | Years of Experience in Management |

| PTVP1* | F M | B.Ed. B.Ed. | 10 yrs. (7 mms*** & 3 Acting) 9 yrs. (6 mms & 3 Acting) |

| PTVP2** | F | Diploma in Education | 22 yrs. (permanent) |

| PTVP3 | F | B.Ed. Honours | 19 yrs. (permanent) |

| PTVP4**** | M | B.A. | 10 yrs. (permanent) resigned. 3x Administrators 2x Acting Principals |

| PTVP5 | M | PhD | 12 yrs. (6 mms & 6 permanent) |

| PTVP6 | M | B.Ed. Honours | 13 yrs. (10 mms & 3 Acting) |

| PTVP7 | M | B.Ed., B.A., LLB | 21 yrs. (permanent) |

| PTVP8 | M | B.Ed. Honours | 9 yrs. (6 mms & 3 Acting) |

* PTVP 1 has two (alternating) acting principals.

** PTVP = Participant Technical Vocational Principal

*** MMS denotes middle management service, i.e., Deputy Principal level in TVET Colleges.

**** PTVP 4: Since the initial permanent principal resigned, one deputy principal acted. The college was then put under administration several times.

Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling method based on the researchers’ judgement about which participants would be the most informative (Robinson,2014). This study used purposive sampling, which entails intentionally selecting a small number of cases from a larger population to conduct an in-depth investigation. The researchers purposively sampled participants for inclusion in this study due to their knowledge and ability to articulate or describe the phenomenon (Polit & Beck 2014). The inclusion criteria depend on the respondent’s potential to provide rich information to the study. According to McMillan and Schumacher (2010), purposive sampling exploits the information obtained from a small sample.

1.2 Research method

This study follows an exploratory qualitative design. Creswell (2014) states that exploratory research is a methodologic approach that investigates research questions that have not previously been studied in depth. This exploratory study by design pursues a qualitative research approach founded on an interpretivist paradigm. According to Brink et al. (2006), data collection is the precise, systematic gathering of information relevant to the research purpose and its objectives. Researchers in this study agreed with Morgan (2022) in using semi-structured interviews as the data collection instrument. This assisted the study in exploring and describing the perceptions of the TVET college principals on the factors that affect success and identify elements that would constitute achievement or management best practices which would, in turn, underpin the recommended model in order to achieve success (Brink et al. 2006). Data was collected at TVET college principals’ offices. The study’s theoretical basis is that the executive role played by the TVET college principals as managers is crucial for improving both the TVET college management success and student achievement (Cotton 2003).The two focal points of the study are (1) success, which relates to improving institutional capabilities to enable TVET colleges to accomplish their work and satisfy their clients (students), and (2) management at the individual level or the principal’s distinct combinations of attributes that make them trump their peers in terms of success (Yang et al. 2018). However, these capabilities cannot solely originate from a single person (principal /manager). Accordingly, factors that affect the success of management point to the TVET colleges principals’ distinct combination of attributes as key for success or failure. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted to gather information about these factors. Interviews were voluntary upon initial request (letters/email) and acceptance to participate (consent forms signed). Interviews were audio taped and later transcribed and coded. Questions were asked based on the main research question and subsequent questions were used to guide the information collected. The answers addressed the lack of support from the senior management at the DHET, delays in replacing or appointing principals, the lack of synergy between the DHET’s plans and TVET colleges’ operational plans, the implementation of the principals’ performance assessment procedures, and finally a myriad of other TVET college service delivery challenges. Document analysis was used to make sense of the research data (Corbin & Strauss 2008). The process involved interpreting data to elicit meaning and gain understanding, and develop critical knowledge of the source documents regarding the topic. Some aspects reflected in the interviews highlighted the positives of TVET college principals’ experiences in managing day-to-day operations (Morgan 2022). The analysis of data involved the research questions (“Factors that impinge on the success of management in TVET colleges in Gauteng province of South Africa”) and the sub-questions study respondents answered on the opinions, experiences and behaviour of the DHET officials through non-numerical data.

2 Research Findings

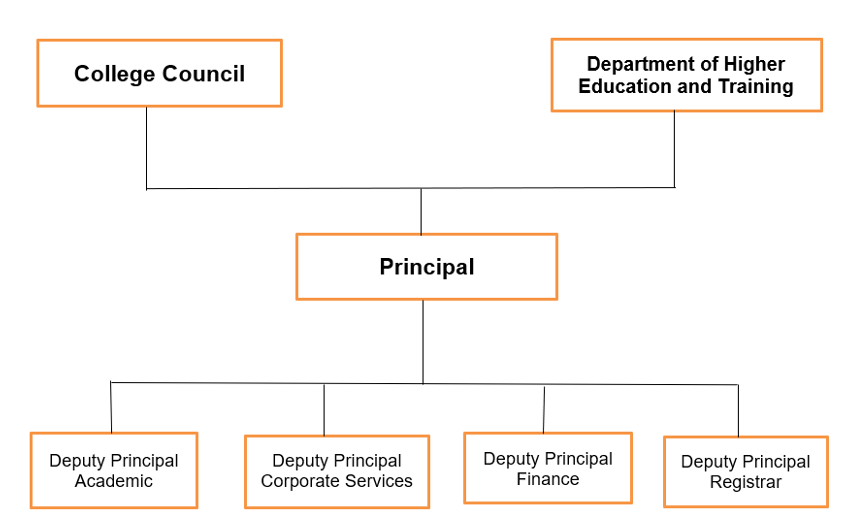

The management structure in TVET colleges in South Africa and in the context of this paper refers to people appointed as principals or chief accounting officers (Schwella & Ketel 2008). The notion of management assumes that the principal possesses supervisory and leadership characteristics. In South Africa, principals are guided by policy and legislation in the management of these institutions; they plan, organise, and control day-to-day operations such as meetings and administration activities and lead committees in order to guide the achievement of specific executive tasks (Juntrasook 2014). TVET college principals also take on the role of leadership, guiding the people who report to them and acting as role models or ambassadors of these institutions. Please see the organisational structure below (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Gauteng TVET College Organisational Structure (Source: adopted South African Government 2014)

The above organisational structure determines roles and responsibilities assigned, controlled, and coordinated at different levels (Singh 2015). The structure also reflects hierarchical power over decision-making and the span of control, such as the role and responsibilities of the DHET, College Council, and the principal over the deputy principals. An effective management structure strives to achieve success, common goals, value-adding relationships, and effective communication between management levels (South African Government 2016).

TVET colleges in South Africa are established under the Continuing Education and Training (CET) Act 2006 (South African Government 2006). The aim is to ensure that TVET colleges are successful in their day-to-day operations and can produce graduates with specific technical and vocational skills. According to the CET Act, TVET colleges are charged with implementing policy, interpreting and articulating these factors into practice. As heads of these institutions, the principals lead, manage and supervise the day-to-day operations. The role of the principal is to lead a roadmap for the realisation of the policy goals for post-school education and training (DHET 2013), which stipulates the outcomes of these goals as an integrated, coordinated, expanded, accessible, responsive, strengthened, cooperative, quality efficient and successful TVET colleges (National Planning Commission 2013). However, TVET colleges are constantly challenged to respond to the country’s requirements with an adequately skilled workforce in order to compete and develop the economy (Nzimande 2012). Successful management involves institutional capabilities and system administration (DHET 2015). Thus, this paper aims to determine how the TVET college principals deal with challenges faced in practice at these institutions and which factors cause a lack of management success. The focus was on the technical, behavioural and overall managerial skills needed for supervisory or leadership roles. A combination of skills, knowledge, behaviours, attitudes, and attributes were explored to determine the success or lack thereof of management.

The initial broad finding is that participants struggled daily to balance the academic demands of the institutions with their professional responsibilities. These institutional and professional demands appear to clash with the DHET’s demands. This added a layer of complexity to the principal’s management responsibilities. During the interviews, some participants reflected that they grapple with balancing internal demands and external expectations. The role of principals as managers in the TVET colleges is critical in ensuring successful performance. However, the findings revealed that managing the current TVET colleges is complex. Findings further brought to the fore issues around the need to clarify the role and responsibilities of the principals. These improvement needs include having assessment standards for the type and levels of principals, as well as knowledge and skills. In addition, findings are also about processes and procedures, performance management and relationships between various stakeholders’ improvement of communication and teamwork. According to respondents, factors determining management success are diverse, such as good management characteristics involving knowledge of the TVET colleges sector, competence, and understanding of the operational context. Issues such as value-adding relationships, cooperation, attitudes, individual growth, critical thinking, adaptability, and creativity were noted. During the analysis of the participants’ responses, their opinions reflected both the negative and positive experiences contributing to success or lack thereof. Participants’ responses to the research questions include:

2.2.1 Q1: What are the critical factors contributing to management success in TVET colleges?

Question 1: What are the critical management factors that contribute to success or lack thereof at TVET colleges?

Theme 1: Competencies to successfully manage TVET colleges.

Participants responded to the question as follows:

“The TVET college I manage operates as if it is new. Yet it has been operating since the transformation of technical colleges into TVET colleges in 2000 and function shift process (movement of the functions, roles, and responsibilities of the TVET sector from the Provincial Department of Basic Education to the Department of Higher Education). It has long been established and repositioned to respond to government policies and mandates. There is a need to perform a skills audit or assessment of the principals, current skills, qualifications, and experience. These are to be matched with staff placement based on their strengths. Upon skill audit, identify training areas.” PTVP5.

Another respondent stated, “PTVP3, recruitment and selection process of TVET colleges principal, the gaps, weaknesses, and lack of succession planning looms large. Advertisement of TVET college principals’ posts to be specific about lived experience, knowledge, planning, managing expertise and attitude emphasised, including the ability to be critical, analytical, and creative”. PTVP3.

The above responses from principals reflect some workplace contextual issues, such as relationships and responsibilities between principals as heads of these institutions and the senior management at DHET Head Offices. These are being raised as an integral part of career success. If negative, this implies that productivity and overall job satisfaction would be impacted. If looked at positively, it means there would be an increase in productivity and satisfaction and improved employee morale (DHET and TVET college principals). Both sides would reflect relations with Fayol’s 14 principles (Brunsson 2008). The contextual factors for understanding the participants’ responses provided the basis to analyse the interview responses.

2.1.2 Q2: What factors impede management success in TVET colleges?

Theme 2: Management challenges.

Some participants respond that:

PTVP3 “TVET colleges principals are instructed, and they comply with what they are told. This created lack of cooperation between the DHET (Head Office & Regional Office) and the reality of managing TVET colleges operationally on a day-to-day basis”. PTVP3.

Another respondent reflected:

PTVP1 “Day-to-day implementation of both DHET and college strategic and operational plans are often very challenging. Performance assessment regime still lacks alignment of the two (DHET and college plans)”. PTVP1. In addition, respondent: “PTVP2, The TVET system has developed policies; however, there is lack of adequate support from Head Office Senior Managers to support college principals in interpretation and translation policies in implementation. This shift led to a lack of clarity in relations between the Head Office, Regional Office, and Colleges; thus, job descriptions are not specific”. PTVP2.

The above-cited participants’ responses amplify the competing pressures and priorities across the offices of the DHET, i.e. the feeling of frustration and a sense of perpetual changes. Dealing with various competing operational issues. Balancing internal (colleges) and external (DHET: Head Office & Regional Office) roles. Lack of streamlined communication. Antitrust regulation and implementation of DHET policies. The literature reviewed, the theory of management by especially Fayol, and issues raised by respondents reflect critical elements in this regard. The reasons for selecting the above-cited responses are based on:

- Emphasis on personal and professional experience

- Focus on top management at both the DHET and TVET colleges.

- A cry for effective relationships devoid of frustrations and competing priorities. The elements presented comprise principles and processes applicable to organisations, including TVET colleges (Brunsson 2008). If turned around, the challenges present TVET Colleges and DHET senior managers with opportunities to identify gaps and understand how the organisations are run (Ramparsad 2022).

In the current study, TVET college principals have to navigate the recent (2015) function shift process (movement of the functions, roles, and responsibilities of the TVET sector from the Provincial Department of Basic Education to the Department of Higher Education), which has brought about additional challenges (DHET 2019).

2.1.3 Q3: What strategies are needed to ensure positive results in developing TVET college management for current and future success?

Theme 3: Managerial professional development

Following the above-mentioned question and the theme, respondents stated that:

PTVP4 “TVET college principals must have sector knowledge, broad understanding of the DHET policies and legislation for leading these constantly changing institutions” PTVP4. In addition, another participant responded: PTVP2, “Workshop principals, when introducing new policies, assist them in interpreting and translating the guidelines into implementation” PTVP2.

Notwithstanding, the above TVET colleges sector remains engulfed by challenges that inhibit it from performing at its best despite government support (Nzimande 2011; DHET 2012). The findings further identified a mismatch between the DHET’s demands from TVET college principals and the reality on the ground, which negatively affects the success of principals. Overall, participants bemoaned the lack of support systems. Some respondents reflected that their employer, DHET, is not supportive. Some stated that senior management at DHET is not well-informed about how TVET colleges operate. This ends up causing tensions and gaps in communication and understanding. These participants argue that TVET colleges are highly specialised and DHET officials lack firsthand sector experience and how these institutions must relate to the workplaces. These factors also raise issues of institutional/organisational coherence and cooperation. Concerning the problems of acting principals, participants raised examples of delays in the selection and recruitment process in filling vacant positions. This inflexibility of the system and lack of support extends to other management areas. Various capabilities for managing and implementing change and achieving success are negatively impacted by a lack of support and an inflexible system. The findings are summarised as:

- Weaknesses in the selection, recruitment and placement of principals

- Prolonged periods with only acting principals

- Inadequate professional development

There is a lack of adequate cooperation and support between DHET senior management and TVET college principals. The above implications are that TVET colleges are not performing as successfully as expected. The country is not producing skilled graduates ready to be deployed into the workforce and positively contribute to the economy. The recommendations below derive from this paper’s findings.

3 Recommendations

These are related to TVET college principals who manage these institutions, the challenges encountered, and the change needed to ensure effective management and increased management performance. DHET senior management is encouraged to collaborate with TVET college principals and establish comprehensive support systems to respond to the TVET college mandate informed by policy.

- The first recommendation is that, given that some principals are appointed permanently, they need to be trained and supported to perform better. Training is key to preparing acting principals to perform better if appointed (acting to permanent). It is recommended that training and development focusing on TVET colleges’ management be prioritised.

- The second recommendation is that relationships at both internal and external levels need to be improved. Internally, the TVET college principal should lead and promote team spirit of unity and coherence among college employees. This would serve as a good foundation for communication, collegiality, and collaboration. Externally, a conducive environment and cooperation with DHET senior management is needed to ensure synergy in the planning and interpretation of plans and implementation of both policies and operational plans.

- The third recommendation concerns performance improvement. The framework that informs the planning needs to be reviewed, and selection and recruitment systems must be made agile to respond to vacancies and resolve the delays in appointments and long periods of acting principals. These improvements would ensure service delivery and productivity, culminating in success.

- The obstacles that block the achievement of success include weaknesses in the selection and recruitment process, lack of continued supply of suitably skilled staff (principals) or succession planning to ensure required competencies for TVET colleges principals. Lack of shared management values by both the DHET senior management and TVET colleges. Finally, coherence and team interconnectivity constitute areas for further research, given the research sample size.

This study discovered factors that hinder success in TVET colleges, including the college principals’ specific knowledge and operational ability. Due to the research questions, participating principals reflected on factors that both hamper and facilitate the achievement of success, their personal experiences, and aspects for and against success. They also highlighted a notable link between success and performance, managing change and how these affect success and lack thereof. An improvement model was proposed for consideration.

4 Conclusion

The paper focuses on the factors that impinge on the success of management in TVET colleges in the Gauteng province of South Africa. The study noted that the targets set in the National Development Plan 2030 and White Paper for Post School Education and Training (PSET) are not being achieved. This, in turn, raises questions about the performance of principals as managers of these institutions. This paper sets out to better understand the experiences of the TVET college principals as managers of these institutions. The problem of low throughput rates in TVET colleges over the years resulted in the DHET not achieving its policy goals.

The conclusions drawn from the findings of this paper are related to TVET college principals’ management challenges, the change needed to ensure effective management, and increased performance. The TVET sector needs to be aware of the obstacles to achieving success and the importance of the criteria that will ensure such success. The additional conclusion is that tailor-made training for principals is needed to ensure efficient management of these institutions. The capacity acquired through the proposed model would enable these principals to deal successfully with current and future challenges. The active involvement of the DHET Senior Management, collaboration with universities, and support from industry would enhance the TVET college management knowledge and experience and allow them to perform successfully. In addition, DHET senior management should lead the implementation of the proposed workforce development model, focusing on principals for current and future successful performance. Finally, the study contributes new knowledge on TVET college management. It seeks to improve the conceptual understanding of key factors and management features needed for TVET college principals in South Africa.

References

Brink, H., Van der Walt, C., & Van Rensburg, G. (2006). Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Health Care Professionals. Cape Town: Juta & Co. (Pty).

Brunsson, K.H. (2008). Some Effects of Fayolism. In: International Studies of Management and Organization, 38(1), 30-47.

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Cotton, K. (2003). Principals and Student Achievement: What the Research Says. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2012). Annual Report 2011/2012. Pretoria: DHET.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2013). White Paper for Post-School Education and Training. Building an expanded, effective and integrated post-school education system. Pretoria: DHET.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2015). Annual Performance Plan 2015/16. 123 Pretoria: DHET.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2016). The Technical and Vocational Education and Training Management Information System (TVETMIS). Pretoria: DHET.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2018). TVET College Examination Results 2018. Pretoria: DHET.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) (2019).Post-school education and training information policy. Pretoria: DHET.

Juntrasook, A. (2014). ‘You do not have to be the boss to be a leader’: contested meanings of leadership in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(1), 19-31.

McMillan, J. H. & Schumacher, S. (2010). Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, Inc.

Morgan, H. (2022). Conducting a Qualitative Document Analysis. In: The Qualitative Report, 27(1), 64-77.

National Planning Commission (2013). National Development Plan 2030: Our future – make it work. Pretoria: The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

Nzimande, B. (2011). National Skills Development Strategy (NSDS) III. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training.

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T. (2014). Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice (8th Ed). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Watkins.

Ramparsad, N. (2022). The Role of Senior Management in Organisational Transformation. In Nicolaides et al. (eds.): The Palgrave Handbook of Learning for Transformation. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Robinson, O.C. (2014). Sampling interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. In: Qualitative Research in Psychology 11(1): 25-41.

Schwella, E. & Ketel, B. (2008). Management Capacity-Building in the South African Police Service at Station Level. In: International Journal of Police Science & Management, 10(2), 145-164.

Singh, R. (2015). The Role of Leadership in Academic Professional Development. Doctoral Dissertation. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

South African Government (2006). Continuing Education and Training Act 16 of 2006. Pretoria: South African Government.

South African Government (2014). Public Administration Management Act 11 of 2014. Pretoria: Government of South Africa. Online: https://www.gov.za/documents/public-administration-management (retrieved 05.02.2025).

South African Government (2016). Human Resource Development Council (HRDC). Summit “Partnership for Skills – A call to action”. Report SA Government. Pretoria: South African Government.

Trochim, W. & Donelly, J.P. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base. Online: https://archive.org/details/WilliamTrochimJamesPDonnellyTheResearchMethodsKnowledgeBase2006 (retrieved 03.02.2025).

UNESCO (2021). UNESCO Strategy for (2022-2029). Transforming TVET. For Successful and Just Transitions, Discussions Document. Paris: UNESCO.

Van der Bijl, A. & Taylor, V. (2016). Nature and Dynamics of Industry-Based Workplace Learning for South African TVET Lectures. In: Industry and Higher Education, 30(2), 98-108.

Yang, M., Zhang, Y., & Yang, F. (2018). How a Reflection Intervention Improves the Effect of Learning Goals on Performance Outcomes in a Complex Decision-Making Task. In: Journal of Business and Psychology; Volume 33(3), 1-15.