Abstract

The model of school-based training in Vietnamese TVET is currently preventing the country from obtaining a qualified workforce. This is due to a skills mismatch. Training in the workplace is, therefore, a pertinent solution to reduce the discrepancy in expectations for qualified labour between employees’ skills and jobs. Companies in Vietnam have tried to conduct training at the workplace over the years. When the industry is based on manual work, the chances of this being successful are higher. However, as Vietnamese industry rapidly shifts to advanced technologies such as CNC, there is an increasingly urgent demand for well-trained workers who can, for example, operate CNC centres independently and solve problems that may occur during their shifts. Strengthening cooperation between TVET stakeholders in Vietnam, in which vocational schools and enterprises play key roles, will enhance the quality of the workforce. This paper intends to provide models of cooperation for TVET in Vietnam, organising formal and informal training with appropriate recognition and accreditations. Moreover, the paper will suggest some possible solutions (curriculum development collaborating, coordinating training, etc.) for strengthening cooperation between stakeholders of TVET in Vietnam in order to make coordination a permanent feature of training.

Keywords: Coordinating in training, curriculum development collaborating, school-based training.

1 Introduction

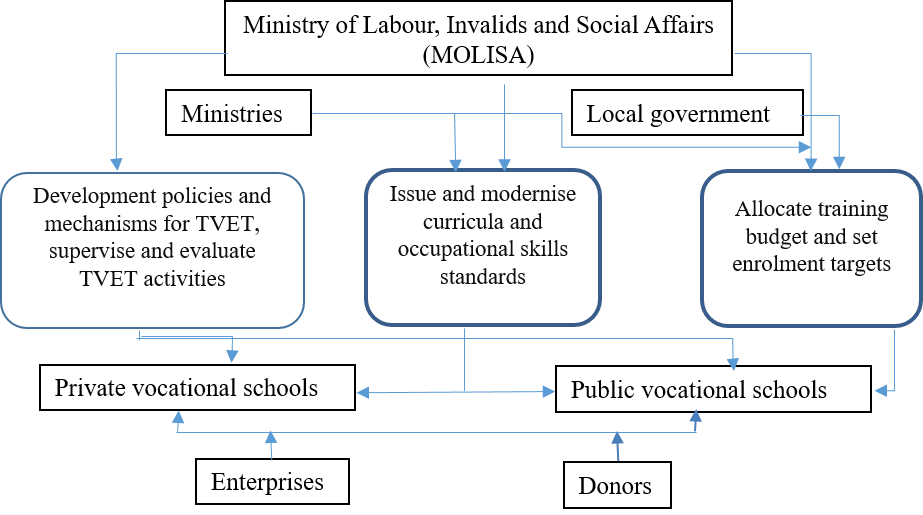

TVET Vietnam is a typically state-driven system in which training activities mainly take place in schools and trainees are isolated from industry due to TVET governance in Vietnam. The Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) plays a major role in issuing and supervising curricula and establishing occupational skill standards (see Fig. 1). This summary shows that corporate interference in the development of curricula and the setting of vocational qualification standards has diminished.

In this top-down management system of TVET, industry can only get involved with TVET training as internship providers. This restricts opportunities of enhancing experiences of the working world to TVET trainees who are employed by companies and spend at least three to six months in manufacturing, for example, during their apprenticeships. However, apprenticeships are often of a superficial nature when there is no clearly defined commitment or consultation between stakeholders (vocational schools who send TVET trainees into companies and the companies where practical training is hosted) in terms of the content of apprenticeships and no direct correlation with professional qualifications which a worker should attain after graduation. Most internships or apprenticeships in TVET Vietnam are organised or promoted are dependent on the goodwill of industry. This can result in trainees failing to gain worthwhile work experiences during their apprenticeships, either because the company does not allow apprentices to participate in their manufacturing procedures or due to unstructured conditions of the working environment. A director of a metal mould producing company admitted that: “Normally, we do not know exactly what we should do with apprentices sent to us by vocational schools, because they – the schools – do not communicate the outcomes of the apprenticeship.” (Source: voice recording, author’s field trip). The statement indicates typical shortcomings in “cooperation and coordination issues” (BIBB 2020, 3) in TVET Vietnam when the TVET system is not built on complementary training content. This situation is magnified by ineffective cooperation between stakeholders. Curricula are issued by the state, marginalising industry’s participation in curriculum development. This, in turn, presents a challenge to enterprises in the recruitment process. It is difficult for them to find qualified workers due to a skills mismatch. Promoting informal training in which trainees are integrated into the workplace and engaged in meaningful professional activities (in the manufacturing industry) would help to solve the skills mismatch problem. Informal training solutions can show workers how to deal with simple or manual operations, but qualified workers – and a highly skilled workforce in particular – could be trained in unique forms of advanced education (vocational school, college and higher) in which they are emerged in stimulating working conditions which bring professional knowledge and skills together. They need to be prepared to face ongoing changes in technology by practising learning and communication skills. A qualified worker can be characterised by the ability to apply knowledge and skills in performing complicated tasks, by demonstrating the capacity to adapt quickly to technological innovation and by creating new knowledge and skills demanded in the workplace, based on what they have learned through training. Skilled industrial workers are competent at applying knowledge, converting their talent into needed skills in manufacturing, developing their abilities and spreading their knowledge in technology transformation (adapted from Mori et al. 2009; Teichler 1995; ILSSA 2014). Kenichi Ohno defines a well-trained workforce as being capable of “manufacturing for the primary purpose of achieving customer satisfaction through high quality in the spirit of a proud and dedicated artisan, rather than just making profits” (Ohno 2009, 9). They are furthermore “expected to engage in higher-order thinking, such as problem solving, decision making, and critical analysis, as part of their jobs, rather than merely performing routine work behaviours” (Jacobs 2019, 8).

The shortage of skilled labour reflects the actual state of TVET in Vietnam. Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI) data, drawn from the 2021 annual report of the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) in collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), states that only 58 percent of workers are trained in the industry and 12 percent are qualified in the labour market (Malesky 2021). This becomes the most problematic factor for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) companies, making it difficult to recruit skilled workers because of an inadequately educated workforce, as noted in the Viet Nam Technical and Vocational Education and Training Sector Assessment of the Asian Development Bank in January 2020 (ADB 2020). Lack of connections with industry is one reason for the inadequately educated workforce in the case of TVET Vietnam. This is generally the weakest point in a state-driven system. It results in trainees lacking sufficient qualifications and underlines the mismatch between the demands of industry and the professional skills of graduate workers when training programmes and curricula are designed in a top-down system (see Fig. 1).

TVET Vietnam is actually in transition from supply-driven skills development to demand-driven skills development with the intention of reducing the skills mismatch, with vocational training schools normally driven by government and employers (including domestic and foreign direct investment companies). The mismatch will become increasingly apparent through the necessity to fulfil industry’s skills demands. The transition or transformation could be supported by reorganising cooperation and coordination issues on the level of governance. The TVET law (Vietnamese Law on Vocational Education and Training) introduced in Vietnam in 2014 is indicative of the transformation which encourages the involvement of employer representatives and enterprises in TVET training in order to enhance commonality in training programmes and to create consistency in training quality assessment (The National Assembly of Socialist Republic of Vietnam 2014). This TVET law addressed many shortcomings such as industry’s participation in TVET training, quality assurance in the TVET system by focusing on standardisation, international integration and permeability, as well as the rights and obligations of enterprises in TVET. Indeed, enterprises’ participation in curricula development and organisation of training are essentiality to build a qualified workforce, work-ready without the need for a phase of integration after they enter employment. For the first time, the law recognises the role of foreign-invested vocational training institutions, as well as giving vocational institutions greater authority to use foreign training programmes of recognised quality to attain training objectives and to cooperate with foreign or international organisations on training activities. Article 34 of the law affords vocational schools and foreign-invested vocational training institutions more freedom to choose and update their training programmes. The law advocates a bottom-up approach to curriculum development which allows for the provision of information about enterprises’ training and recruitment needs as input for the process of curriculum design. Consequently, there are some successful examples of training coordination in the Vietnamese TVET system, such as the cooperation between the state-run vocational school Lilama-2 International Technology College and Bosch Vietnam Company. This is considered as best practice in TVET Vietnam, with a programme designed for dual training activities. Participants in the dual programme will spend three quarters of their training engaged in practical work within Bosch Vietnam’s vocational training centre and one quarter based at the LILAMA2 vocational institution for theoretical education relating to the profession. Bosch Vietnam’s dual vocational training programme with the Lilama College is, an exemplary training programme based on German standards, in which all assessments are conducted in reference to German Chamber of Industry and Commerce. Moreover, informal learnings at the workplace, such as training programmes to enhance vocational knowledge and skills, apprenticeships, technology transfer programmes are now acknowledged as continuing training programmes in relation to Article 40 of the TVET law (The National Assembly of Socialist Republic of Vietnam 2014). They can be granted degrees of college-level or vocational secondary schools and certificates in elementary-level vocational training. This change will help to strengthen industry involvement in TVET.

Piloting Skills Councils is another sign of the transformation to demand-driven skills development in TVET Vietnam, fostering the institutionalisation of employers’ involvement in founding National Vocation Qualifications (NVQs) (NIVT 2019). Unfortunately, participation levels of companies, especially domestic ones, have yet to meet expectations. In-house training under the conditions outlined in Article 34 of the TVET law should have obvious training objectives for each level (elementary, intermediate and college) and clear parameters for the knowledge and skills of graduates. There should be clarity and specificity to the structure of the curriculum, methods and types of training; methods of accreditation of learning outcomes applied to each module, course credit, subject, major, or vocation and level (adapted from the Article 34 of the Vietnam TVET law) (The National Assembly of Socialist Republic of Vietnam 2014). This is a huge challenge for economic sectors in Vietnam. Most domestic private companies lack the personnel, finances and capabilities to build systematic in-house training which would help them to overcome the scarcity of a qualified workforce. They could mentor their own employees after recruitment on a track from apprentice to journeyman to master. Such a system could see an apprentice take instruction from an experienced technician for a mentoring period of 6 months, for example. During this time, the newcomer would learn as much as possible in terms of skills which can be independently deployed in the workplace thereafter. If training is not framed by legally regulated conditions, it can be unreliable and overly dependent on the qualifications and enthusiasm of the instructor. Therefore, adapted training could be considered as informal training without standardised references such as a specific training syllabus training materials to assure that self-study is available to trained workers. This is essential when facing the challenge of rapid changes in manufacturing technology at the workplace in the future. Many companies have tried standardising the work and then converted tasks into scrutinised behavioral components. Training at the workplace in domestic companies is only functional when a worker fulfils certain working duties which are already divided into simple procedural steps or sets of actions and only has to imitate particular behaviours according to instructions. In some cases, manufacturing procedures are organised according to a belt-driven moving assembly line, with groups of workers assigned to tasks at designated work stations, small in size and limited in responsibility. For instance, a CNC operator just has to push a button to stop and start the machine. Other important tasks are done by a core team. The focus on functional training saves time and is more cost-effective for firms but may impact negatively on a company’s human resources during draining and fails to address contemporary demand.

2 Tripartite partnership in TVET Vietnam as a suitable governance model in TVET Vietnam

The shortage of a well-trained workforce is a key consideration for TVET Vietnam, echoed by many representatives of industrial societies such as EuroCham (European Chamber of commerce in Vietnam), JICA (Japanese International Cooperation Agency) Vietnam and the World Bank. The JICA have even assisted the government in promoting a tripartite partnership model, based on “constant interaction with industry” (JICA 2014, 10). A dedicated core of process training management in which training demands are provided by industry and used as materials for curricula development represents the first in a series of seven procedural steps. During training management, connections and conversations are directly sustained to keep training programmes aligned with industry requirements. Curricula are updated annually to account for demand related to latent skills. Evaluation of training programmes and graduates’ qualifications are also important strategic areas for improvement in TVET, implemented through annual meetings between vocational institutions and enterprises to assess industry’s demands. Industry links would help TVET schools or colleges to tailor advanced training at the workplace via short-term courses. Bringing educators from TVET institutions into contact with the reality of the working world will help to improve practical training lessons in schools (adapted from JICA 2014). The tripartite partnership in TVET Vietnam, introduced by JICA, is a real breakthrough, starting from one small step by the Japanese FDI Company MUTO, the first company in Southern Vietnam to organise systematic internal training for mold and dies technicians. The in-house programme has been running since 1998. In their efforts to overcome the lack of mold and dies workers, the company later expanded training for neighbouring companies’ workforces. The company has now even established an institute for training technicians in the field of molds and dies for the whole country. This can be seen as an autopoietic system: a self-organised training activity in which the company strives to solve the shortage of suitable labour by training its own workforce in accordance with demand, independently producing and maintaining the company’s manufacturing capability through the repetition of its own operations – with reference to (Chilean biologists) Maturana and Varela’s definition of the autopoiesis system. In this system, industry tries to handle problems by itself due to the lack of in-house training, the lack of involvement of vocational institutions and the absence of recognised training qualifications. The Korean enterprise Samsung has established a similar model to Bosch, cooperating with not only one, but many, local vocational schools to provide evening courses for its workforce. In this cooperative operation, the company plays also the role of internship host and acts as a consultant on the development of training curricula at partner TVET institutions. Another example of cooperation in conducting training programmes is Vietnam Singapore College (VSC), which established the Singapore Industrial Area in Vietnam. Having begun with short training courses from 3 to 6 months for workforces in the industrial area, it has grown into a vocational college offering basic training courses and bachelor’s courses. The clustering in TVET Vietnam as described in the case of Samsung and VSC, linking a college to companies in the area to design and conduct training courses together, can be viewed as a typical tripartite partnership cooperation in TVET. Finally, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in Vietnam is an important element in the foundation of tripartite partnerships in TVET Vietnam, strengthening cooperation between vocational colleges and the business sector. Local enterprises are more involve in nurturing a qualifying workforce and the aforementioned partnership has promoted many training programmes with a curriculum designed under supervision of the administrative body – the Directorate of Vocational Education and Training (DVET). TVET institutions are involved, as are local professional associations such as the Water Supply and Drainage Association with regard to sewage engineering technicians, for example. All programmes operate on a cooperative basis in dual learning places – schools and workplaces. Tripartite partnership can assure the quality of trained human resources and prevent the risk of functional training by maintaining annual coordination between stakeholders of TVET, organised in a legitimised framework. Training curricula issued in the tripartite partnership are tailored to the exact requirements of human resources’ needs in industry. Although the tripartite partnership has many advantages and could be a solution for training up highly-skilled workers, it has yet to make a significant impact on Vietnamese firms due to a lack of depth in the field of personnel management and the absence of appropriate support from state-run TVET institutions. If domestic companies initiate in-house training, they can respond to the challenges of defining demand at the workplace, acknowledging the realities of the working world, as well as outlining and conducting training programmes. Vietnamese enterprises need support in standardising training at the workplace to build their workforce, in collaboration with state-run TVET institutions.

3 Model of school-industry collaboration – lessons learned from the German Industry and Commerce Vietnam (AHK Vietnam) concept

Enhancing involvement from industry and improving standardisation of enterprise-based training in the TVET system are priorities in Vietnam. German companies in Vietnam usually train their qualified workforce according to the dual system and German standards. This entails the AHK Vietnam looking for vocational schools which can meet requirements on facilities, personnel and curriculum. They must also demonstrate a readiness for cooperation in training with industry partners, once the AHK has ascertained demand from companies. In the AHK concept, training activities are conducted in two learning places: vocational schools or colleges as partners in the dual training system for theoretical knowledge and companies (as hosts of dual training system), where apprentices sharpen their labour skills. By combining theory and practice, the integration of the trainee into working processes can be ensured from the beginning. On-the-job training in a dual system provides knowledge for each individual business and practical work experience during the training period. The GIC/AHK Vietnam plays the role of first contact point, training consultant and coordinator during training. Moreover, the quality of education is ensured by the monitored structure and administration of AHK, providing services with the scope of not only finding Vietnamese vocational training centres as cooperation partners, but also advising interested companies on how to set up, develop and implement suitable training programmes in Vietnam. Finally, the GIC/AHK Vietnam performs examinations, manages certification and bases qualifications in line with German DIHK standards. The model of dual training according to German standards has the advantage of transparent information exchange in TVET and underpins consistency in the coordination of training programmes. The curriculum is implemented with two learning places in mind: school and company.

Lesson learned from the AHK concept:

- Training in a dual system should be organised in two different and specific learning places: vocational schools or colleges are the best and most suitable training hubs for delivering theoretical and professional foundations, and partners in industry as spaces where apprentices can build their personal working experiences through daily training activities.

- Partnership between two main relevant stakeholders in TVET is guaranteed by AHK as consultant and coordinator – the service provider plays an important role in monitoring the quality of training and providing assessment.

- Consistency in training can be controlled transparently through a curriculum which is based on the realities of the working world.

- Assessing activities via third parties helps to secure the quality of training.

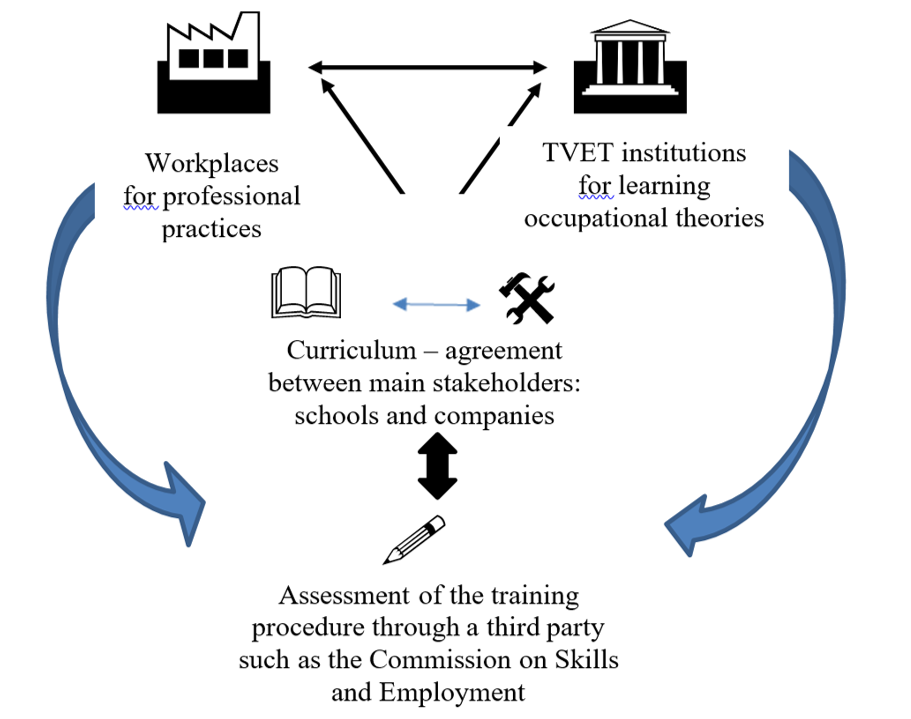

From the lessons learned above, a model for effective school-industry collaboration can be depicted (Figure 2) which demonstrates the triangular relationship between three important stakeholders in the TVET system: schools or TVET institutions, industry and third parties for assessment – normally professional associations. Training takes place in dual learning sites and activities are conducted with direct reference to the curriculum – underpinned by official commitment between two partners in the system. The curriculum is designed to encompass skills requirements and analysis of work in order to clarify the need for qualification in a specific occupation. Information resources and materials are incorporated into the design of training theory, whilst practical lessons can make the training process more transparent for stakeholders industry and vocational institutions, as well as making the process of qualifying trainees more effective. According to this model, assessment should be done via a third party from industry, representative of companies who lead the market in the field. Professional associations are the most suitable candidates for this position. The central point of the model is the curriculum. All training activities should be linked to qualification, assessment and recognition of trainees.

The model advocates the involvement of industry in training not only as hosts for workplace experience, but also as contributors or consultants in the development of curricula and as observers in assessment and qualification processes. The suggested model is an open allopoiesis system (adapted from the allopoiesis system as defined by Maturana and Varela, two Chilean biologists) – in which requirements and updates from the working world are more easily documented and amended in the training curriculum. Moreover, the model can help processes become more reliable and unbiased through assessment by third parties. The model encourages intervention of important stakeholders of TVET Vietnam in creating a training community which pledges to train a qualified workforce and expand their contribution to the entire Vietnam TVET system, thus ensuring the quality of training. It may help to accelerate completion of a national qualifications framework in TVET Vietnam and boost the participation of companies in TVET.

4 Conclusion

TVET Vietnam has struggled to establish an effective concept of governance which is capable of increasing participation of industry representatives in training activities. Until now, one only player has taken on this task – TVET state-run and private institutions. Curriculum development, training assessment and qualifications are also crucial elements of TVET. So long as curricula are designed by TVET institutions without industry participation, training cannot be at its most effective. The same is true of assessment, which can be unreliable without greater participation of stakeholders in the assessment process. This, in turn, lessens the chances of bridging the gap between TVET training at vocational schools and the needs of industry. Insufficient information on the skills and qualifications required from the perspective of industry, especially latent skills, makes it difficult to build suitable training programmes or create useful training materials. Without the input of industry, the contents of training programmes tend to be too far removed from the realities of the workplace. Inappropriate enterprise-based training could lead to inadequate teaching of skills and ineffective management of skills development. Industry needs highly skilled graduates who are expected to possess proper competencies such as self-reliance, intellectual thinking, communication skills in technology, etc. However, insufficient industry involvement in TVET Vietnam hinders TVET’s efforts to prepare the workforce of the future. On the other hand, many domestic enterprises have initiated their own in-house training schemes in order to tackle the skills shortage in the workforce. Training in the workplace is still considered as informal activity due to lack of didactic instruction, clearly structured courses and trained trainers who are capable of staging training activities in the workplace. TVET Vietnam now needs to boost industry involvement in TVET systems and governance. Training strategies in each company need to be connected and networked into a single system, with TVET institutions supporting industry in designing curricula and developing didactical training methods. Trainers themselves require training as well. An effective model of collaboration is a priority for the Vietnam TVET system. The establishment of a social community in TVET would engender a cooperative spirit and lead to a more effective system of training a highly- skilled workforce to meet the needs of industry and FDI enterprises. The model of school-industry collaboration would motivate key TVET stakeholders to cooperate in preparing a qualified workforce for modern industry.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2020). Viet Nam. Technical and Vocational Education and Training Sector Assessment. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (BIBB). (2020).Assessment of the implementation of the Vietnamese Vocational Training Strategy 2011-2020 and recommendations for the Vietnamese Vocational Training Strategy 2021-2030. Bonn: BIBB. Online: assessment-of-the-implementation-of-the-vietnamese-vocational-training-strategy-2011-2020-and-recommendations-for-the-vietnamese-vocational-training-strategy-2021-2030.pdf (sea-vet.net) (retrieved 15.12.2022).

Flake, R., Kumar, P., Ngangom, T., Brings, C., Simelane, T., & Ta, M. T. (2017). The Role of the Private Sector in Vocational and Educational Training: Developments and Success Factors in Selected Countries. Berlin: EPF Working Paper.

Institute of Labour Science and Social Affairs (ILSSA). (2014). Skilled Labour – A determining factor for sustainable growth of the nation. In: Policy Brief, 1, 1-4. Geneva: ILO. Online: https://www.ilo.org/global/docs/WCMS_428969/lang–en/index.htm (retrieved 05.01.2023).

Jacobs, R. L. (2019). Work Analysis in the Knowledge Economy: Documenting What People Do in the Workplace for Human Resource Development. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (2014). Promoting Tripartite Partnerships to Tackle Skills Mismatch: Innovative Skills Development Strategies to Accelerate Vietnam’s Industrialization. Hanoi: JICA Viet Nam Office. Online: https://www.jica.go.jp/vietnam/english/office/others/c8h0vm00008ze15n-att/policy_paper.pdf (retrieved 04.07.2019).

Malesky, E. J. (2021). The Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI 2021). Measuring economic governance for business development. Hanoi: Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI).

Maturana, H. R. & Valera, F. J. (1987). The Tree of Knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications.

Mori, J., Thuy, N. T. X., & Troung Hoang, P. (2009). Skill Development for Vietnam’s Industrialization: Promotion of Technology Transfer by Partnership between TVET Institutions and FDI Enterprises. Hiroshima: Hiroshima University. Online: Microsoft Word – 10_Skills Development for Vietnam_FINAL.doc (researchgate.net) (retrieved 05.01.2023).

National Institute for Vocational Education and Training (NIVT). (2019). Viet Nam Vocational Education and Training Report 2019. Hanoi: National Institute for Vocational Education and Training. Online: 220426-Vietnam-VET-Report-2019-EN.pdf (tvet-vietnam.org) (retrieved 05.01.2023).

Ohno, K. (2009). Avoiding the Middle-Income Trap: Renovating Industrial Policy Formulation in Vietnam. In: ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 26, 1, 25-43. Online: Avoiding the Middle-Income Trap: Renovating Industrial Policy Formulation in Vietnam on JSTOR (retrieved 06.01.2023).

Teichler, U. (1995). Qualifikationsforschung. In Arnold, R. & Lipsmeier, A. (eds.): Handbuch der Berufsbildung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 501-508.

The National Assembly of Socialist Republic of Vietnam. (2014). Law on Vocational Education. Hanoi: Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Online: Law-on-Vocational-Education-No.-74-Year-2014.pdf (asean.org) (retrieved 05.12.2022).

Voice recording manuscripts of author’s interviews from field trips.