Abstract

For many years, the concept of competentcy and quality of the workforce has been prevalent around TVET world. Top performers contribute to a tremendous impact on organizations’ productivity and overall performance. Therefore, identifying top performers is crucial for organizational success and workforce planning. Once identified, those top performers can be targeted for development and a planned progression throughout the organization. However, there are limited indications on how to identify top performers within and across organizations. Thus, the objectives of the current study are to measure the competencies of workers and to develop a competency profile. Using Malaysian hotels sector as the research setting, a survey was employed using a newly-developed questionnaire as the competency measurement instrument. The aim of the study is to measure the competencies possessed by culinary professionals in the Malaysian hotel sector. There are 111 culinary professionals who participated in the survey. The data analysis used the Rasch Measurement Model. From the findings, there are 61 respondents who show an outstanding performance (54%). About 17 of them appear to be superior performers, at a position one standard deviation above the Mean Person (15%). The findings of the competency assessment demonstrated that organizations are able to gather data on the quality of their current workforce. This study also provides a mechanism on how to identify top performers in organizations using the data gathered from the competency assessment.

Keywords: Competency, Competency Profiling, Culinary Professionals, Self-Assessment

1 Introduction

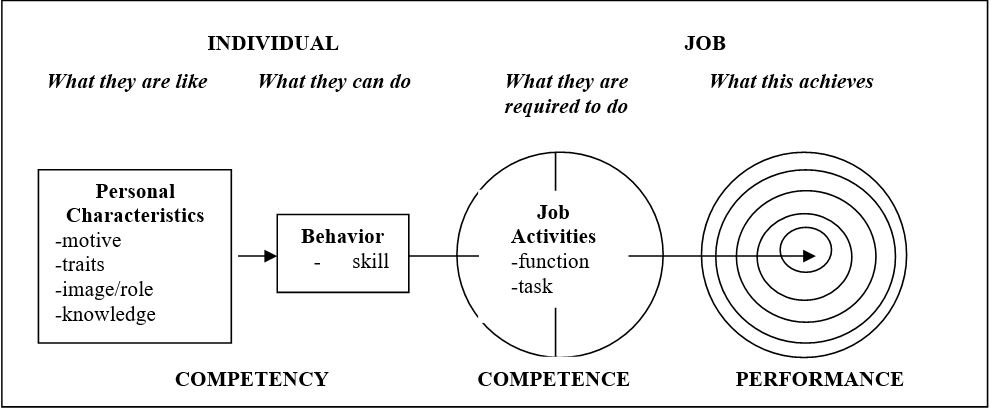

Managing employee performance through competencies has been discussed widely in organizational behavior and human resource management literature (Dadgar, Janati, Tabrizi, & Asghari-Jafarabadi 2012; Guest 2011; Ahadzie, Proverbs, & Olomolaiye 2008). According to Scholl (2003) and Eberts (2012), attracting and retaining high-quality employees is an important managerial objective. This is especially true for organizations that require highly skilled and motivated employees. A system of performance measures need to be integrated as part of the workforce system. A well-designed and effective performance management system should be managed properly in order to drive continuous performance among employees of the organizations. Tan (2001) suggests that employees are certainly the “excellence-enablers” of an organization because quality people can bring about organization excellence. He also emphasized that organizations must have an effective talent development strategy in order to develop their employees’ competence and commitment. Based on Sarawano’s (1993) model, Young & Dulewicz (2005) develop a model (Figure 1) which links competency and competence to performance. It identifies competency as personal characteristics (traits, motives, image/role and knowledge) and how the person behaves (skill). In their study, competence is what a worker is required to do – the job activities (functions, tasks). These in turn lead to the performance of the individual.

Figure 1: A model linking competency and competence to performance Source: Young & Dulewicz (2005, 229)

Since the early 2000s, there has been a substantial amount of studies emphasizing the concept of competencies (Garavan & McGuire 2001; Weigel, Mulder & Collins 2007; Axley 2008; Barth 2009). Apparently, much of the literature on competencies has mainly focussed on defining the concept of competencies (Burrus, Jackson, Xi & Steinberg 2013; Zhang, Zuo & Zilante 2013). As an eminent term in the human resource landscape of corporate organizations, competency is often defined as knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviour, and other attributes that define and contribute to work performance. Employees who have the required competencies for the job will demonstrate the understanding and ability to perform their job task well. Previous studies have shown that assessing the competency of the workforce is one of the endeavors in improving work performance. In the area of performance measurement systems, a broad array of assessment has been conducted. In the context of workplace-related psychological testing, assessment is defined as an appraisal of personal characteristics, behaviors and human processes through techniques such as interviews, observations and tests (Potgieter & Merwe 2002). Competency assessment is often conducted in form of self-assessment, employers’ evaluation or 360-degree-feedback. This approach helps to determine the relevance of the organizational performance and its components (Getha-taylor, Hummert, Nalbandian, & Silvia 2012).

It is imperative that self-reported competencies could provide data in order to understand the competencies of current workforce in industry. A thorough competency assessment through self-assessment is important in a way that it would allow industry to know where they stand, and how education and training contribute to the profession. Several authors (Coltman, Devinney, Midgley, & Venaik 2008; Haynes, Richard, & Kubany 1995; Lietz 2008) asserted that self-rated questionnaire is also one type of test. These authors highlighted that beliefs that people have about their own interests and capabilities pose a strong impact on how individuals complete any inventories and made specific decisions after considering the given options. On an individual level, self-assessment is significant to efficiently plot the direction of an individual’s professional career. According to Getha-Taylor, Hummert, Nalbandian, & Silvia (2012), self-assessment improved the quality of employees by providing analyses on how they function successfully in the chosen career. In organizations, whether the organization uses the information or not, self-assessment is an essential method for the development of proficiency. Self-assessment studies on workers have yielded rich information that benefits human resource management of organizations.

2 Competencies and performance management for quality assurance of labour market

Organizational quality is dependent on two aspects; the quality of the workforce (Ranjit Singh Malhi 2001) as well as the identification of critical needs and resources for the changing workplace (Society of Human Resource Management 2008). These two aspects are important for todays’ contemporary hospitality industry. The industry is labor-intensive, employing a wide variety of individuals, each having a unique experience, skills sets, and motivational pattern. Thus, the challenge for human resource management is to manage the human capital in an effective manner so that individual performance can be well-managed (George 2008). Undoubtably, the level of workers’ competency reflects the quality of the labour market. In many professions, competency standards define the qualifications required to practice in the respective disciplines. According to Lysaght & Altschuld (2000) and Trinder (2008), competency standards is one of the measuring tools of workforce quality. Standards and benchmarking is the key to regaining global competitiveness. There is a huge benefit from establishing a competency-based standard for a profession such as, increasing labor market efficiency, enhancing career progression by providing a valid basis for promotion, and providing the basis for initial and ongoing professional education (Gonczi, Hager, & Oliver 1990).

2.1 Challenges for culinary professionals

In most commercial organizations, the ultimate purpose is to provide value to customers. In the face of globalization trends in the area of culinary tourism, much emphasis was put on the profession. Culinary professionals need to be equipped with certain competencies that will enable them to carry out quality work performance. For high-rated hotel establishments, the demand for skillful culinary professionals is huge. However, industry has encountered an astounding lack of competent workers. Fine dining establishment such as upscale restaurants and hotel require culinary workers to be more flexible in dealing with the demands of the contemporary world of work. Culinary careers encompass the combination of competencies in both the aspects of culinary and science. Mohd Salehuddin, Mohd Hairi, Muhammad Izzat, Salleh & Zulhan, (2009) proposed that culinary professionals nowadays must have an array of skills and be knowledgeable of the vast area of food such as science and technology in the food preparation as well as food consumption and marketing in order to meet the needs of the industry. Thus, it can be inferred that a professional culinary artist must have a great knowledge concerning variety of cooking techniques as well as the science behind food creation. Prestigious fine dining restaurants earned their reputation by tantalizing their guests with outstanding menu items with an exceptional taste, texture, and food presentation (Shahrim 2001; Chalmers 2008; Tittl 2008). As one of the most challenging professions in the hospitality and tourism industry (Zopiatis 2010), culinary professionals are those who are responsible for maintaining the high quality of foodservice in the hospitality related operations.

2.2 TVET qualifications for culinary professionals in Malaysia

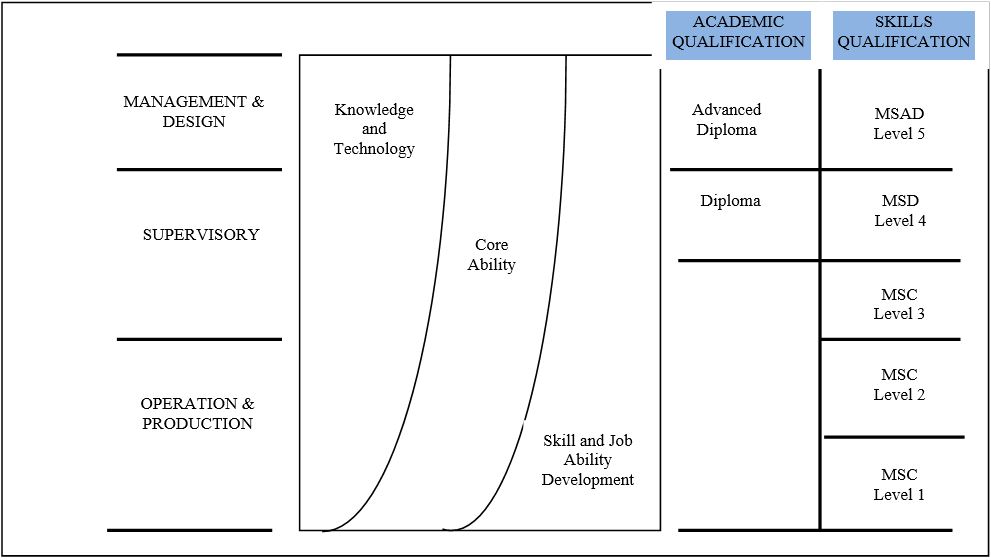

The Department of Skills and Development (Ministry of Human Resources) and Ministry of Education Malaysia have established the National Occupational Skill Standards (NOSS) that defines the employment level and essential competency level which need to be fulfilled by industrial employees. The skills standards were developed to provide guidance for workers with an ideal career pathway. Figure 2 shows the Structure of Malaysia Occupational Skills Qualification (MOSQ).

Figure 2: Structure of Malaysia Occupational Skills Qualification (MOSQ)

As shown in the Figure 2, the higher levels of the Malaysia Occupational Skills Qualification (MOSQ) which are Level 4 and Level 5 are equivalent to the Diploma and Advanced Diploma of Malaysia Academic Qualification, whereas Level 1 to Level 3 is equivalent to Certificate of Malaysia Academic Qualification. For the MOSQ skill certification, NOSS is used as the main criterion in determining the level of competencies which the trainee required (Department of Skills Development 2013). Hospitality and tourism is one of the sectors listed in the NOSS directory for skills profession related to TVET. One sub-sector which addressed culinary art area is kitchen management. Table 1 below shows the field of study and five category levels of MOSQ for the kitchen sub sectors based on the NOSS. The course of Hotel Culinary (HL01) has been developed for the National Dual Training System (NDTS). This literally highlights the importance of culinary art as an essential niche in the hospitality and tourism industry.

Table 1: Sub sectors (Kitchen)

| Level | Cooking | Pastry | Bakery | Butchering |

|

HT-012-5 Food Preparation and Production Service |

HT-013-4 & 5 Pastry and Bakery Management |

Not available |

||

| L4 |

HT-012-4 Food Preparation and Production Service |

|||

| L3 |

HT-012-3 Food Preparation |

HT 014-3 Pastry Production |

HT 013-3 Bakery Production |

HT 011-3 Senior Butcher |

| L2 |

HT-012-2 Food Preparation |

HT 014-2 Pastry Production |

HT 013-2 Bakery Production |

HT 011-2 Junior Butcher |

| L1 | No level | No level | No level | No level |

| *HL01 | Hotel Culinary | |||

Source: Department of Skills Development (2013)

Certainly, culinary art is a vital element in Malaysian hospitality and tourism industry as the travelling experience would be unforgettable and become the most appreciated part of the entire journey (Salehuddin, Hairi, Izzat, Salleh, & Zulhan 2009; Shahrim, Chua & Hamdin 2009). Moreover, hospitality and tourism has been listed among sectors for development in the National Key Economic Activities (NKEA) of Economic Transformation Program in Malaysia. It can be seen that synergizing hospitality, tourism and culinary have become a major focus of the Malaysian government to spur economic growth of the country. As food and beverages is one of the core components of the sector, the need for skilled personnel from the food preparation industry is in demand. The number of people employmed in the industry represent almost 14 percent of the total Malaysian labor force (NKEA 2011, Chapter 10). Thus, culinary tourism certainly presents promising needs and demands for employment of competent, well-prepared and dedicated chefs, administrators and managers in the areas of hotel, food service, restaurant, food manufacturer, catering and hospitality-related fields who can work together in providing the best food and services for guests and consumers (Rozila & Noor Azimin 2011).

Great emphasis on hospitality and tourism has brought changes to the culinary art education landscape in Malaysia from primary school to higher educational levels at universities. For TVET graduates in Malaysia the typical route to qualification starts as early as the secondary school system. Culinary art education is offered by the technical and vocational institutions such as secondary schools (elective course in Living Skills subject), vocational schools, community colleges and polytechnics (Mohd Amin, Sahul Hamed & Mohd Ali 2012). In recognition of the importance of culinary art education from secondary school on, the Ministry of Education has included Catering and Food Preparation subjects as one of the Vocational subjects that give great opportunity for students who are interested in this field to start articulating their cooking skills. Vocational education in culinary art and home economic education act as a fundamental platform for school students who are interested in cooking and food preparation to start crafting their career path in the field of culinary art. In conjunction with this, the Malaysia National Accreditation Board released an established guideline on criteria and standards for culinary art courses in July 2004. This guideline is a fundamental resource for all institutions of higher learning formulating new curricula especially for the private institutions as these institutions widely offer three educational levels of culinary art education which are certificate, diploma and Bachelor degree. The standard provides useful information for culinary curriculum such as the learning outcomes and course designs. This standard also allows institutions to have room for creativity and innovations to suit their program objectives with current job and employment requirements. Further, the National Modular Certificate Program, a skill training program, has been introduced to students in Polytechnic and Community Colleges in order to expose the students to the world of work. This program provide the opportunity for the participants to take part in the up-skilling and reskilling courses, as well as training attachment in response to industry needs (The Department of Community College, Ministry of Higher Education 2010).

2.3 Needs for competency identification and profiling

Nowadays, there are growing interests in the study of competency and its profiling. Previous studies have shown that competencies are important for superior work performance (Lee 2010; Orr et al. 2010; Stines 2003). These authors suggest that competencies are required to support lifelong learning, to be transferable, to be capable of being learned, and to be generic. They discuss the need for competencies to correlate with job performance, to be measurable, and to be capable of being improved via training and development. In the area of the tourism and hospitality sector, Lertwannawit, Serirat, & Pholpantin (2009) have conducted a study on the relationship between career competencies and career success. The findings revealed that employees’ competencies are positively associated with the success in their career. Knowledge in hospitality and tourism has an impact on career success, as well as leadership style, team work value, and computer and language skills. According to Shellabear (2002), competency profiling is typically a method used to identify specified skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour necessary to fulfill a task, activity or career. Competency profiles have been applied within many professional groups to guide career progress as well as to uphold the image of the profession. Constructing realistic and meaningful competency profiles is important for assisting human resource management in organizations to identify and evaluate their employees’ work performance. This practice also gives opportunity for organizations to evaluate their strength, and to recognize development areas. The analysis of the competency profile will help with organizational planning on how to address competency gaps. Therefore, there is a need for competency profiling, which is done through job competence assessment as a method to identify employees who are valuable to the organizations and those who need improvement through professional career development programs. This is possible by studying what high performers actually do, focussing on the person in the context of the job, generating behaviorally-specific data which are useful for assessment and training and, identifying the competencies most critical to good performance (Abdul Aziz et al. 2008; Ali, Kaprawi & Razzaly 2010; Campion et al. 2011).

The need for appropriate structures in identifying workplace competency profiles was already highlighted by Saunders (1998). In his study, the findings show that the utilization of competency profiles help employers in job specification, employee selection, and employee training and assessment. However, the study reported that the use of workplace competency profiles is very limited among training providers. Employers agree that competency profiles might be useful; however, there is little indication on the existence of any competency profiles that could be used as a point of reference. Additionally, Jackson (2009) addresses the need for a fresh approach in profiling the competencies. The lack of substantiated guidance on industry requirements is the most prevalent hindrance factor in educating well-qualified graduates. Highlighting the concept of competencies is important during the delivery of educational interventions and training as well as in the actual profession. Current studies by Subramonian (2008), Lee (2010) and Che Rus, Yasin & Rasul (2014) urged the need to identify industry-relevant competencies so that further training and education interventions could be implemented in order to bridge the competency gaps. Systematic competency profiling will facilitate competency gap analysis. Hence, the current study shed light on a development process of competency profiling for culinary professionals in 4 and 5 starred hotels in Malaysia. One hopes that the study will broaden the vision on the lists of competencies required for high performance in culinary profession.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

The study started with the identification of important competencies for culinary profession in the context of Malaysia. Qualitative interviews with nine culinary experts were carried out at the initial stage. A competency framework which encompasses the lists of competencies was developed. Further, a content validity procedure (Content Validity Ratio, Lawshe (1975)) was conducted among twelve subject matter experts (SMEs) to categorize the competencies into Threshold (T) and Differentiating (D) competencies. A competency assessment instrument named Star-Chef Self-Assessment Tool (SC-SAT) was developed based on the identified competency constructs. A quantitative survey was carried out among 111 culinary professionals who work in 4-star and 5-star hotels in Malaysia.

3.2 Instrument

The present study explores the implementation of a newly-developed tool, the Star-Chef Self-Assessment Tool (SC-SAT), for assessing competencies in culinary profession (Suhairom, Musta’amal & Mohd Amin 2014) in six competency areas; Technical, Non-Technical, Personal Quality, Self-Concept, Physical State and Motive. The tool was designed for the self-assessment of competencies of culinary professionals who work in a hotel setting.

3.3 Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Winstep 3.72.3, a Rasch-based software. Further, this study demonstrated the development of competency profile using the Rasch Measurement Model. The data which were analyzed using Rasch analysis were utilized to develop the competency profile of the culinary professionals based on their self-reported competencies using the SC-SAT instrument. The item strata were utilized in the study. To construct strata in identifying the performance level of the culinary professionals, the formula used is

The strata are defined as statistically distinct measures as suggested by Fisher (1992) and Wright & Masters (2002). By this means, the level of competencies among culinary professionals could be classified into several categories based on their responses in the SC-SAT instrument. These performance indicators were used as a guideline for determining the performance levels of culinary professionals for the competency profile development. This method was initialized by Grosse & Wright (1986) and then refined in their work (Wright & Grosse 1993). In the current study, “essential” items refer to items which represent sub constructs in the differentiating (D) categories, whereas the “optional” items refer to items which represent sub constructs in the threshold (T) category. The decision confidence as agreed by the experts is 90% mastery of the differentiating competencies. This is considered important for superior work performance in the culinary profession. This method is suggested by Bond (2003) and Wang (2003) as a scientific approach for standard settings. The method was also followed by several standard setting studies in Malaysian context which focused on determining the performance cut score (e.g. Nuraini, Azami, Azrilah & Jaafar Riza (2013) and Zamaliah, Saidfudin, Azrilah & Zaharim (2011)).

4 Findings

A cross-sectional survey of a random sample of culinary professionals in 4-star and 5-star hotels was conducted. There are 111 culinary professionals who responded to the study. Of these 61 work in 5-star hotels and 50 respondents works in 4-star hotels. The majority of the respondents are Malay (83.8%), followed by Chinese (9%), Indian (4.5%) and Others (2.7%). Most were male (66.7%). About 52.3% of them hold managerial level position (Chef de Partie and above) while 47.7% work at non-managerial level (Commis/Cook). In terms of educational background, the majority of them were Diploma holder in Culinary Art (53.2%), followed by high school graduate (43.2%). There are three respondents who have a Degree and one respondent who has a postgraduate educational accomplishment.

For methods of culinary training and education attainment, 66 respondents (59.5%) reported that they learnt about culinary from culinary schools or institutions. The other 40.5% of the respondents learnt culinary through experiences. About 83.8% of the respondents have experience working in foreign countries. A large percentage of the respondents (84.7%) do not have the MOSQ (Malaysia Occupational Skills Qualification) certification.

4.1 Identification of threshold and differentiating competency

Results from the content validity procedure among subject matter expert (SME) on the identification of Threshold (T) and Differentiating (D) competencies are presented in Table 2. Experts who were involved in the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) process were asked to classify the competencies into two categories: They decided if the competencies are “threshold” or “differentiating” the employees’ work performance. By this, competencies are categorized into threshold (T) and differentiating (D). Based on experts judgment, technical competency is made up of six threshold and nine differentiating competency.

Meanwhile, most of the Non-Technical sub constructs were identified as differentiating competencies except for Professionalism and Moral Ethics. Physical State is rated as threshold competency. Personal Quality, Self-Concept, and Motives were rated as differentiating competencies. Experts also agreed that 90% level of mastery in the differentiating competencies is required for a superior work performance in culinary profession. Overall, there are eight (8) threshold competencies and thirty-six (36) differentiating competencies in the framework of Star-Chef Competency Model.

Table 2: Identification of Threshold and Differentiating Competencies

| COMPETENCIES | THRESHOLD | DIFFERENTIATING |

| Technical: culinary- specific | ||

|

Kitchen operations |

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

| Aesthetics |

|

|

| Creative |

|

|

| Innovation |

|

|

| Kitchen and catering services |

|

|

| Science |

|

|

| Nutrition |

|

|

| Costing |

|

|

| Quality |

|

|

| Hygiene |

|

|

| Safety |

|

|

| Research |

|

|

| Non-technical: generic competency | ||

| Social intelligence |

|

|

| Emotional intelligence |

|

|

| Cognitive intelligence |

|

|

| Professionalism and moral |

|

|

| Management |

|

|

| Leadership |

|

|

| Lifelong learning |

|

|

| Entrepreneurship |

|

|

| Career |

|

|

| Personal Quality | ||

| Personality |

|

|

| Physical State | ||

| Physical |

|

|

| Self-Concept | ||

| Occupational Preferences |

|

|

| Motives | ||

| Motives |

|

|

| 8 | 36 | |

4.2 Competency profiling

This study provides information about standard setting in employees’s performance evaluation using the Objective Standard Setting (OSS) method which can be implemented for organizations in Malaysia. The competency profiling was developed based on the data from the culinary professionals’s self-assessment of competency using the SC-SAT instrument which contains 159 items on competencies. The SC-SAT instrument yield item reliability is 0.94 with separation index of 4.02 and person reliability 0.99 with separation index of 8.78. To construct the competency profile, the calculated item strata is [4(4.02) +1] / 3 = 5.69. Thus, the performance towards SC-SAT instrument can be separated into 6 levels, which are Excellent, Very High, High, Mediocre, Low and Very Low. The judgment of the subject matter expert (SME) towards the differentiating competencies required for superior work performance among culinary professionals was referred to. Based on the identified 36 differentiating competencies and 8 threshold competencies, there are 125 differentiating items and 34 threshold items in the SC-SAT instrument. With an expectation of 90% mastery of differentiating competencies, there are 112 items that need to be taken into account. The 125 differentiating items were divided into 6 performance levels, resulting 21 differentiating items in each performance levels. In each level, the item measure is summed up and divided by the number of items in each group to establish the mean of item measure (in logits) and cutscore for the respective performance levels. Table 3 shows the details regarding the indicators of performance levels. Based on the list of performance levels indicators, the cut-scores for performance levels were identified through the Item Measure Order Table generated by the Winstep*.

Table 3: Indicators of Performance Levels

| Group (Performance Level Indicators | Item Measure (logit) | No of items | Mean (logit) | Standard Error (SE) |

| Group 1 (Outstanding) | MGM5 (+0.82) to SCI1 (+1.72) | 21 | 1.10 | 0.14 |

| Group 2 (Very High) | CAR3 (+0.43) to CUL3 (+0.80) | 23 | 0.58 | 0.15 |

| Group 3 (High) | COG5 (+0.01) to EST2 (+0.43) | 29 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

| Group 4 (Mediocre) | PS15 (-0.33) to MGM3 (+0.01) | 32 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Group 5 (Low) |

SC3 (-0.64) to MOT 1 (-0.33) |

30 | -0.46 | 0.16 |

| Group 6 (Very Low) | MOT14 (-1.74) to PS2 (-0.64) | 24 | -0.99 | 0.17 |

| Total items | 159 |

Further, the expected 90% competency mastery level of 112 items is identified and bookmarked at item FIN2 (I have knowledge in managing procurement of supplies) with measure of +0.97 logit. With this Rasch analysis, the demarcation line was produced and thus, enabled a thorough analysis of the grading pattern according to performance level. The established demarcation line is superimposed on the Person Measure Order Table*. The expected ‘mastery’ level of 90% agreed at +0.97 logit located at the Very High Performance level. There are 61 respondents who show an Outstanding performance (54%). About 17 of them appear to be the superior performers, at position one standard deviation above the Mean Person (exceed +3.10 logit). There are 12 performers who perform at a Very High level (11%). There are 12 respondents found to be at the level of High performers (11%) and three Mediocre performers (3%). There are six culinary professionals who were classified as Low performers. There is no respondent who falls into the Very Low performance level.

A detailed analysis was conducted on the Item Order Measure Table to identify the categories of the competencies whether the competencies falls into threshold (T) or differentiating (D) categories as shown in Table 4:

Table 4: Order Measure Table

| No. | Measure (logit) | Item | Construct | Sub constructs | Category | |

| 1 | 1.72 | SCI1 | Technical | Science | Differentiating | |

| 2 | 1.41 | SCI2 | Technical | Science | Differentiating | |

| 3 | 1.39 | FIN5 | Technical | Costing | Differentiating | |

| 4 | 1.36 | NUT1 | Technical | Nutrition | Differentiating | |

| 5 | 1.32 | FIN4 | Technical | Costing | Differentiating | |

| 6 | 1.26 | SCI4 | Technical | Science | Differentiating | |

| 7 | 1.24 | NUT5 | Technical | Nutrition | Differentiating | |

| 8 | 1.22 | NUT2 | Technical | Nutrition | Differentiating | |

| 9 | 1.18 | SCI3 | Technical | Science | Differentiating | |

| 10 | 1.07 | CUL2 | Technical | Culture | Differentiating | |

| 11 | 1.07 | NUT3 | Technical | Nutrition | Differentiating | |

| 12 | 1.03 | NUT4 | Technical | Nutrition | Differentiating | |

| 13 | 0.99 | RES4 | Technical | Research | Differentiating | |

| 14 | 0.97 | FIN2 | Technical | Costing | Differentiating | |

| 15 | 0.97 | QUA1 | Technical | Quality | Threshold | |

| 16 | 0.89 | CRE3 | Technical | Creativity | Differentiating | |

| 17 | 0.89 | FIN1 | Technical | Costing | Differentiating | |

| 18 | 0.87 | INO1 | Technical | Innovative | Differentiating | |

| 19 | 0.87 | ENT2 | Non-technical | Entrepreneurship | Differentiating | |

| 20 | 0.82 | RES1 | Technical | Research | Differentiating | |

| —————————————————————————————– | ||||||

| 139 | -0.72 | HYG2 | Technical | Hygiene | Threshold | |

| 140 | -0.75 | SOC4 | Non-technical | Social Intelligence | Threshold | |

| 141 | -0.80 | OPS4 | Technical | Kitchen Operations | Threshold | |

| 142 | -0.80 | SC2 | Self-concept | Attitude | Differentiating | |

| 143 | -0.80 | PS4 | Personal Quality | Openness | Differentiating | |

| 144 | -0.80 | PS16 | Personal Quality | Extroversion | Differentiating | |

| 145 | -0.88 | SC1 | Self-concept | Attitude | Differentiating | |

| 146 | -0.91 | OPS7 | Technical | Kitchen Operations | Threshold | |

| 147 | -0.91 | SC4 | Self-concept | Value | Differentiating | |

| 148 | -0.91 | MOT12 | Motive | Sense of Worth | Differentiating | |

| 149 | -0.94 | MOT11 | Motive | Sense of Worth | Differentiating | |

| 150 | -0.99 | PS10 | Personal Quality | Conscientiousness | Differentiating | |

| 151 | -1.05 | PS9 | Personal Quality | Conscientiousness | Differentiating | |

| 152 | -1.05 | PS11 | Personal Quality | Conscientiousness | Differentiating | |

| 153 | -1.10 | PS5 | Personal Quality | Agreeableness | Differentiating | |

| 154 | -1.22 | PS6 | Personal Quality | Agreeableness | Differentiating | |

| 155 | -1.25 | PS1 | Personal Quality | Openness | Differentiating | |

| 156 | -1.28 | PS7 | Personal Quality | Agreeableness | Differentiating | |

| 157 | -1.37 | PS8 | Personal Quality | Agreeableness | Differentiating | |

| 158 | -1.58 | MOT13 | Motive | Sense of Worth | Differentiating | |

| 159 | -1.74 | MOT14 | Motive | Sense of Worth | Differentiating | |

*Note: Please contact the corresponding author for detailed Winstep analysis

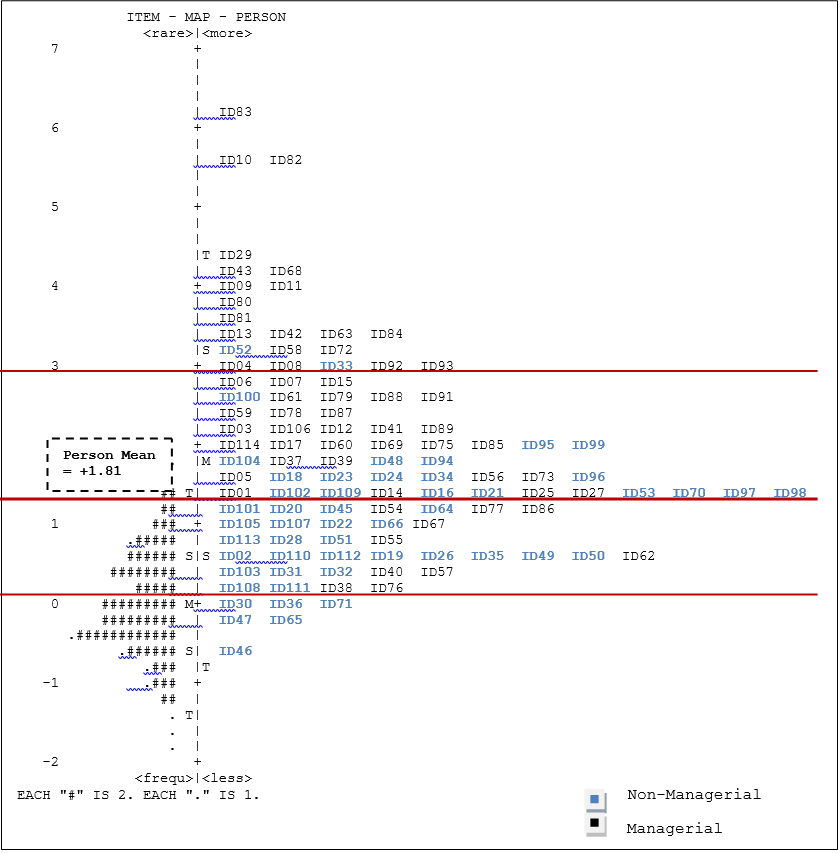

A detailed analysis was conducted on 20 items at the highest logit position and 20 items at the lowest logit position. Among 20 items at the highest logit position, only one item from Technical construct falls into the threshold competency category. This item is QUA1 (I am able to prepare Quality Checklist as one of the food quality assurance monitoring documentation). The majority of the items at the lowest logit position are from the constructs of Self-concept, Personal Quality and Motive; which identified previously as differentiating competency by the experts. However, there are three items identified from the threshold competency category which are the SOC4 (I can work in teams very well) from the Non-technical construct and, OPS4 (I know various cutting techniques in preparing foods), OPS7 (I am able to organize ingredients in readiness for food preparation) and HYG2 (I comply to hygiene rules while in food preparation) from the Technical construct. Figure 3 illustrates the Item and Person map where the position of the items and person can be observed more clearly. It can be shown that there are eight persons from the non-managerial group in job positions as Commis and Cook with logits located above the Person Mean. Whereas there are 17 persons from the managerial group positioned below the Person Mean.

<< Figure 3: Item-Person Map in Competency Profiling based on SC-SAT Instrument

Figure 3: Item-Person Map in Competency Profiling based on SC-SAT Instrument

Table 5 shows the demographic profile of managerial persons who were positioned at logit below the person mean with reference to age, gender, educational background, working experience and MOSQ certification. To be more specific, the analysis only emphasized on those who are below one Standard Deviation from the Person Mean (ID40, ID57, ID38 and ID76). It was found that all of the culinary professionals have no MOSQ certification.

Table 5: Background of the Managerial Group (Below Person Mean)

| ID |

Age (years) |

Gender | Job Post | Education | Culinary Training/ Education |

Working Years |

Work in Foreign Country |

| ID40 | 36-45 | Male | DC | High School | Experience | 11-15 | No |

| ID57 | 36-45 | Male | DC | High School | Experience | 16-20 | No |

| ID38 | 36-45 | Male | DC | High School | Experience | 16-20 | No |

| ID76 | 18-25 | Female | CDP | Diploma | Culinary school | < 5 | No |

*DC= Demi Chef, CDP=Chef dePartie

The demographic profile of persons from the non-managerial position (Commis and Cook) whom logits located above the Person Mean were also analyzed. It was also found that all of them have no MOSQ certification.

Table 6: Background of the Non-Managerial Group Positioned Above Person Mean

| ID |

Age (years) |

Gender | Job Post | Education | Culinary Training/ Education |

Working Years |

Work in Foreign Country |

| ID52 | 26-35 | Female | Commis | Diploma | Culinary school | 6-10 | Yes |

| ID33 | 26-35 | Female | Commis | Diploma | Culinary school | 6-10 | No |

| ID100 | 36-45 | Male | Cook | High School | Experience | 11-15 | No |

| ID95 | 18-25 | Female | Commis | Diploma | Culinary school | < 5 | No |

| ID99 | 26-35 | Female | Commis | High School | Experience | < 5 | No |

| ID104 | 26-35 | Male | Commis | High School | Experience | 6-10 | No |

| ID48 | 18-25 | Male | Commis | High School | Experience | < 5 | No |

| ID94 | 18-25 | Male | Commis | High School | Culinary school | < 5 | No |

5 Discussion

In organizational management, various research has been conducted to measure workforce performance by using competency levels. Findings from this study provide important information regarding competencies of culinary professionals in 4 and 5-starred hotels in Malaysia. The resulting profile shows that the majority of the culinary professionals have a high mastery level of competencies in culinary. The current study indicates that our Malaysian culinary industry indeed has a substantial numbers of superior culinary talents. It can be observed that 15 percent of superior performers were identified among those who are in the groups of Outstanding Performance. Thus, this study provides insights that using the SC-SAT instrument, competency can be measured and eventually a competency profile which aims at the mastery level of culinary professionals could be developed.

In TVET, we work towards competency-based assessment to measure vocational competence. Prior to measuring vocational competence, self-assessment on individuals’ competencies could provide initial data on the competencies of our current employees in the industry. As mentioned by Coltman, Devinney, Midgley, & Venaik (2008), Haynes, Richard, & Kubany (1995) and Lietz (2008), the utilization of self-assessment is beneficial in assessing the competency of a person. Moreover, the successful implementation of performance management systems through competency assessment depends on the development of reliable measures. The development of instruments to measure specific competencies for a targeted job could facilitate the identification of competency gaps among employees. Thus, in the current study, the newly-developed SC-SAT can be seen as the basis for the development of competency assessment instruments for other profession within TVET.

Findings of the study also provide insights on the role of experience towards an individual level of mastery. The study made it possible to gauge the sources of these competencies where the study identified culinary professionals who hold low level job position but have competency levels above those who are in better positions and formal qualifications. Undeniably, the development of individual professional expertise depends on their formal or informal learning. In the context of skilled workers, it should be noted that learning through experience is one of the most common methodology for skills acquisition. Experience plays a role as the source of learning and development. According to Kwon, Bae & Lawler (2010), a competent individual is intensely influenced by the mastery of experience. Towards embracing the demanding 21st century workplace, skilled workers must have the ability to demonstrate their experience innovation, which refers to the ability in managing information gained from working experience to encounter a contemporary culinary career.

Nevertheless, currently there is a limited indication of a specific mechanism for identifying the competencies possessed by existing professionals in the industry. The findings of this study contributed to generating relevant data that could be used to guide improvement interventions in the industry. The developed profile could be linked to the current technical and vocational education of culinary professionals in Malaysia. Reliable competency profiling could enhance the quality of our vocational education. In line with the recommendations by Orr, Sneltjes & Dai (2010), competency profiling is one of the best practices for selecting, developing and deploying talents. For individuals, Mahazani, Noraini, & Wahid (2010) suggested that competency profile could be integrated into competency management system where employees can have a single view of all their talent management information: development plans, succession plans, performance assessments and appraisal. The Malaysian government has embarked on important missions to increase the number of highly skilled workers in the industry. There is a continued new movement toward applying to and beginning a specific degree or accredited culinary programs with the intention to earn specialized-graduate certifications while actually working towards a diploma or degree.

In Malaysia, the certification scheme such as offered by the MOSQ framework as well as Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) may even count toward credit for a graduate degree. The RPL scheme was developed by the Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF), an agency under the Ministry of Human Resources. Through RPL Scheme, industry workers are able to obtain recognition on their skills and competency according to the level determined by the Department of Skills Development (DSD). This scheme will also encourage workers with skills and experience to apply for MOSQ framework such as Malaysia Skills Certification (MSC), Malaysia Diploma Skills (MDS) or Malaysia Advanced Diploma Skills (MSDS) according to their competency levels.

However, in our local context, awareness towards the benefits and importance of such skills certification is, as yet, very shallow. Up to now, any regulatory approaches to continuing competence as well as professional licensure for chef’s professions are not available. Therefore, issues, particularly those related to professional licensure, are significant concerns. Furthermore, preparing oneself for a professional licensure will benefit culinary professionals to strengthen their positions in the industry as well as to stay relevant on the cutting edge of our culinary industry. Indeed, professional certifications for culinary professionals in Malaysia are not yet available. However, the benefits are significant as one of the platforms to corroborate their hard work, expertise and achievements, and to gain recognition for their skills, knowledge and experience. Professional designations have become almost a requirement to be hired for many job areas such as in education, banking, insurance, project management, risk management, business, law, finance, and various other fields. In fact, professional culinary certification schemes for chefs have been globally established by the World Association of Chefs Society (WACS 2013). Furthermore, in the culinary world, the Michelin star system in Europe is the best-known and most respected ranking system for high-quality or haute cuisine restaurants and their chefs (Johnson et al. 2005). The Michelin star chefs were tremendously successful as culinary artisans. Certainly, such professional certifications uphold the value creation which reflects the quality of a person in the profession (Ehrmann, Meiseberg, & Christian 2009).

6 Conclusion

The success of performance management system relies on how organizations identify and manage the quality of workforce. Competencies could be collaboratively identified and should reflect the dynamic nature of work. It is possible to create a culture of success in organizations provided that the organizational missions are emphasized and the employees‘ career development is supported. Competency profiling, if designed and managed effectively, is a valuable tool for both the individual and the organisation. It has the potential to facilitate training, development and learning, making a measurable increase to performance and profits. To maximise return at all levels, the highlighted competencies should be considered within the context of the evolving needs of the organizational business and culture. Once the organisation has identified its business objectives and defined their processes to deliver to customer requirements, they then have to define the time, costs and quality standards of each task. The competencies are then identified for each task in the key areas of skill, knowledge, attitude and behaviour. It is essential to have documented specific behavioural evidence of a competence achieved. Once defined, this framework provides the infrastructure for the approach to be rolled out throughout the organisation. The findings of the study suggested that it is important to develop a benchmark or mastery levels for competency in order to make it possible for a person to evaluate their own competency. For performance management, the ability of individual workers to demonstrate a certain level of competency mastery according to a specific benchmark assists in leading towards successful performance in a job position. Benchmarking offers a standard mechanism in describing competency mastery for individuals and specific job position. Competency profiling offers potentials in improving the quality of the performance management system.

References

Ahadzie, D. K., Proverbs, D. G., & Olomolaiye, P. (2008). Towards developing competency-based measures for construction project managers: Should contextual behaviours be distinguished from task behaviours? In: International Journal of Project Management,26, 6, 631-645.

Ali, M., Kaprawi, N., & Razzaly, W. (2010). Development of a new empirical based competency profile for Malaysian vocational education and training instructors. In: Proceedings of the 1stUPI International Conference on Technical and Vocational Education and Training Bandung, Indonesia, 10-11 November 2010.

Axley, L. (2008). Competency: A concept analysis. In:Nursing Forum, 43, 4, 214-222. Blackwell Publishing Inc.

Aziz, A. A., Mohamed, A., Arshad, N., Zakaria, S., Zaharim, A., Ghulman, H. A., & Masodi, M. S. (2008). Application of Rasch Model in validating the construct of measurement instrument. In: International Journal of Education and Information Technologies,2, 2, 105-112.

Barth, M. (2009): Assessment of key competencies – a conceptual framework. In: Adomßent, M., Barth, M., Beringer, A. (eds.): World in transition – Sustainability perspectives for higher education. Frankfurt: VAS Verlag, 93-100.

Björkman, I., Ehrnrooth, M., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., & Sumelius, J. (2013). Talent or not? Employee reactions to talent identification. In: Human Resource Management, 52, 195–214.

Bond, T.(2004).Validity and assessment: a Rasch measurement perspective. In: Metodologia de las Ciencias del Comportamiento, 5, 2, 179-194.

Burrus, J., Jackson, T., Xi, N., & Steinberg, J. (2013). Identifying the most important 21st century workforce competencies: An analysis of the Occupational Information Network (O* NET).ETS Research Report Series, 2, i-55.

Campion, M. A., Fink, A. A., Ruggeberg, B. J., Carr, L., Phillips, G. M., & Odman, R. B. (2011). Doing competencies well: Best practices in competency modeling. In: Personnel Psychology,64, 1, 225-262.

Chalmers, I. (2008).Food Jobs: 150 Great Jobs for Culinary Students, Career Changers and Food Lovers. Beaufort Books.

Che Rus R., Yasin R. M., & Rasul, M. R. (2014). From zero to hero: Becoming an employable knowledge worker (k-worker) in Malaysia. In: TVET@Asia, issue 3, 1-16. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue3/che-rus_etal_tvet3.pdf (retrieved 30.06.2014).

Coltman, T., Devinney, T. M., Midgley, D. F., & Venaik, S. (2008). Formative versus reflective measurement models: Two applications of formative measurement. In: Journal of Business Research,61, 12, 1250-1262.

Dadgar, E., Janati, A., Tabrizi, J. S., Asghari-jafarabadi, M., & Barati, O. (2012). Iranian Expert opinion about necessary criteria for hospitals management performance assessments. In: Health Promotion Perspectives, 2, 2, 223-230.

Dawson, A., Wehner, K., Gastin, P., Dwyer, D., Kremer, P., & Allan, M. (2013). Profiling the Australian high performance and sports science workforce. Deakin University, Melbourne, Vic. Deakin Research Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30060700 (retrieved 20.04.2016)

Department of Skills Development (2013). Directory of Skills Profession. Ministry of Human Resource Malaysia.

Ehrmann, T., Meiseberg, B., & Ritz, C. (2009). Superstar effects in deluxe Gastronomy–An empirical analysis of value creation in German quality restaurants. In: Kyklos,62, 4, 526-541.

Fisher, W., Jr. (1992). Reliability, Separation, Strata Statistics. In: Rasch Measurement Transactions, 6, 3, 238.

Garavan, T. N., & McGuire, D. (2001). Competencies and workplace learning: Some reflections on the rhetoric and the reality. In: Journal of Workplace Learning,13, 4, 144-164.

George, A. A. (2009).Competencies for graduate culinary management degree programs: Stakeholders’ perspectives (Doctoral dissertation, Morgan State University).

Getha-taylor, H., Hummert, R., Nalbandian, J., & Silvia, C. (2012). Competency Model design and assessment : Findings and Future directions. In: Journal of Public Affairs Education, 19, 1, 141–171.

Gonczi, A., Hager, P., & Oliver, L. (1990). Establishing competency-based standards in the professions. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Grosse, M.E. & Wright, B.D. (1986). Setting, evaluating, and maintaining certification standards with the Rasch model. In: Evaluation and the Health Professions, 9, 267-285.

Guest, D. E. (1997). Human resource management and performance : A review and research agenda. In: The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8, 3, 263-276.

Haynes, S. N., Richard, D., & Kubany, E. S. (1995). Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. In: Psychological Assessment,7, 3, 238.

Jackson, D. (2009). Profiling industry-relevant management graduate competencies: The need for a fresh approach. In: International Journal of Management Education,8, 1, 85-98.

Johnson, C., Surlemont, B., Nicod, P., & Revaz, F. (2005). Behind the Stars: A concise typology of Michelin Restaurants in Europe. In: Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly,46, 2, 170-187.

Kaprawi, N., Razzaly, W., & Ali, M. (2011).Development of a new empirical based competency profile for Malaysian Technical Vocational Education and Training Instructors(Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia).

Kwon, V. A. P. K., Bae, J., & Lawler, J. J. (2010). High commitment HR practices and top performers. In: Management International Review,50, 1, 57-80.

Lee, Y.-T. (2010). Exploring high-performers’ required competencies. In: Expert Systems with Applications, 37, 1, 434-439.

Lertwannawit, A., Serirat, S., & Pholpantin, S. (2009). Career competencies and career success of Thai Employees in tourism and hospitality sector. In: The International Business & Economics Research Journal, 8, 11, 65-72.

Lietz, P. (2008).Questionnaire design in attitude and opinion research: Current state of an art. Jacobs Universiti: FOR 655.

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. In: Personnel Psychology, 28, 563-575.

Lysaght, R. M., & Altschuld, J. W. (2000). Beyond initial certification: The assessment and maintenance of competency in professions. In: Evaluation and Program Planning,23, 1, 95-104.

Malhi, R. S. (2013). Creating and sustaining: A quality culture. In: Journal of Defense Management,S3:002.

Mohd Amin, Z., Sahul Hamed, A. W., & Mohd Ali, J. (2010). Transformational of Malaysian’s polytechnic into university college in 2015: Issues and challenges for Malaysian technical and vocational education. In:Proceedings of the 1st UPI International Conference on Technical and Vocational Education and Training, 570-578.

Mohd Salehuddin, Z., Mohd Hairi, M. J., Muhammad Izzat, Z., Mohd Radzi, S., & Zulhan, O. (2009). Gastronomy: An opportunity for Malaysian culinary educators. In: International Education Studies, 2, 2, 66.

NKEA, Chapter 10 (2011). Online: http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/sub_page.aspx?id=422954ca-7469-4ae4-a34c-4771941e6fde&pid=3efe6dd8-bc83-44a8-9ebc-26b720409bb8&print=1 (retrieved 26.07.2016).

Khatimin, N., Zaharim, A., Aziz, A. A., Sahari, J., & Rahmat, R. A. O. (2013). Setting the standard for project design course using rasch measurement model. In:Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), IEEE, 1062-1065.

Orr, J. E., Sneltjes, C., & Dai, G. (2010). The art and science of competency modeling: Best practices in developing and implementing success profiles. Los Angeles: The Korn/Ferry Institute, 1-16.

Potgieter, T. & Merwe, R. P. Van. (2002). Assessment in the workplace: A competency-based approach. In: SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 28, 1, 60-66.

Rozila, A., & Noor Azimin, Z. (2011). What it takes to be a manager: The case of Malaysian five star resort hotels. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research, 2040-2051.

Saunders, J. (1998).Indicators of Competency: Profiling Employees and the Workplace. National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Australia.

Shahrim, M. A. K., Bee-Lia Chua, & Hamdin, S. (2009). Malaysia as a culinary tourism destination: International tourists’ perspective. In: Journal of Tourism, Hospitality & Culinary Arts,1, 33, 63-78.

Shellabear, S. (2002). Competency profiling: definition and implementation. In: Training Journal-Ely, 16-19.

Society of Human Resource Management (2008). Retaining Talent. Online: https://www.shrm.org/about/foundation/research/documents/retaining%20talent-%20final.pdf (retrieved 26.07.2016).

Stines, A. C. (2003). Forecasting the competencies that will define “ best-in-class” business-to-business market managers : An emergent Delphi-Hybrid competency forecasting model (Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University).

Subramonian, H. (2008). Competencies gap between education and employability stakes. In: TEAM Journal of Hospitality & Tourism,5, 1, 45-60.

Suhairom, N., Musta’amal, A. H., & Amin, N. F. (2014). Validity and reliability of instrument measuring culinary competencies: The Rasch Measurement Model. In: The Proceeding of International Education Postgraduate Seminar 2014, 695.

Tan, K. C. (2001). A comparative study of 16 national quality awards. In: The TQM Magazine,14, 3, 165-171.

The Department of Community College, Ministry of Higher Education (2010). Malaysian Higher Education: Sustaining Excellence. Online: http://repository.um.edu.my/36836/1/buku%20kpt.pdf (retrieved 26.07.2016).

Tittl, M. (2008). Careers that Combine Culinary and Food Science. In: Careers in Food Science: From Undergraduate to Professional. New York: Springer, 267-275.

Trinder, J. C. (2008). Competency standards a measure of the quality of a workforce. In: The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XXXVII. Part B6a, Beijing.

Wang, N. (2003). Use of the Rasch IRT model in standard setting: An item mapping method. In: Journal of Educational Measurement, 40, 3, 231-253.

Weigel, T., Mulder, M., & Collins, K. (2007). The concept of competence in the development of vocational education and training in selected EU member states. In: Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 59, 1, 53-66.

Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (2002). Number of person or item strata. In: Rasch Measurement Transactions, 16, 3, 888.

Wright, B. D., & Grosse, M. (1993). How to set standards. In: Rasch Measurement Transactions, 7, 3, 315.

Young, M., & Dulewicz, V. (2005). A model of command, leadership and management competency in the British Royal Navy. In: Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26, 3, 228-241.

Zamaliah M., Saidfudin M., Azrilah A.A., & Zaharim A. (2011). Standard setting for engineering education achievement test in an institution of higher learning Malaysia. In: Proceeding of the 10thWSEAS (EDU’11).

Zhang, F., Zuo, J., & Zillante, G. (2013). Identification and evaluation of the key social competencies for Chinese construction project managers. In: International Journal of Project Management,31, 5, 748-759.

Zopiatis, A. (2010). Is it art or science? Chef’s competencies for success. In: International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29, 3, 459-467.

Citation

Suhairom, N., Musta’amal, A. H., Mohd Amin, N. F., Nordin, M. K., & Ali, D. F. (2016). Quality indicators in the field of culinary professions in Malaysia – a method of developing competency profiling through self-assessment. In: TVET@Asia, issue 7, 1-22. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue7/suhairom_etal_tvet7.pdf (retrieved 2.8.2016).