Abstract

This study examines skills shortages as well as growth and transformation in the manufacturing industry in Lao PDR and explores training preferences of employers in the sector. The research draws on a survey of 144 formal sector companies, focusing on the Garment, and Food & Beverage industries. The results reveal that both industries have undergone significant growth and transformation. The Food & Beverage sector has witnessed remarkable expansion, while the Garment industry has demonstrated resilience and adaptability. Although some skills shortages exist, particularly in the Food & Beverage industry, the study finds surprisingly few challenges in filling positions despite rapid economic growth. Manufacturing companies prioritize hands-on skills and experience over formal education when hiring. They provide on-the-job training to upskill employees with low levels of education. Most companies do not rely on training provided by formal training institutions, as they perceive TVET graduates as lacking the necessary skills and experience. This article highlights the need for a more accessible and effective TVET system to meet the demands of the labor market and contribute to the growth of the manufacturing industry in Lao PDR.

Keywords: TVET, Growth and transformation, Skills shortage, manufacturing industries, Lao PDR.

1 Introduction

Between 2000 and 2019, the economy of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) grew at an annual rate of 7 %. This rapid growth can be attributed to a combination of capital investment and productivity increases, not least in the natural resource sector (Asian Development Bank 2022). Despite a temporary slowdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, by 2022, the country had already resumed its rapid growth trajectory. After growing 2.5% in 2021, the Lao PDR economy has accelerated to 3.8% in 2022 (World Bank 2022). Recognizing the importance of fostering a dynamic economy, the Laotian government has prioritized the growth and promotion of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) as a means for developing human capital. This commitment is evident in the TVET development plan for 2021–2025 as well as other important strategic documents (e.g., the 10th Party Resolution, the 8th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan of the Government, and the Strategic Plan for Poverty Reduction (Ministry of Education and Sports 2020)). Through the Strengthening Technical and Vocational Education and Training (STVET) project, funded by the Asian Development Bank, Lao PDR has witnessed a 25 % increase in the number of workers with formal TVET qualifications in the labor force between 2011 and 2021. The ultimate goal of this project, and the government agenda more broadly, is to establish an accessible TVET system that can effectively meet the demands of the labor market, leading to a more skilled and diversified workforce. According to UNESCO’s 2020 TVET country profile, there are three primary challenges that need to be overcome in relation to TVET education. First, there is a lack of sufficient financial support for TVET schools, exacerbated by an absence of appropriate financing schemes. Second, persistent skills mismatches exist, partly attributable to inadequate training resources and equipment, coupled with a deficiency in teaching skills and industry experience among faculty members. Lastly, TVET struggles with a diminished appeal when contrasted with general education. Various studies have examined skills shortages and the role of TVET in Lao PDR. For instance, Leuang (2016) found that graduates from TVET institutions frequently express frustration over their inability to transition into the industry after completing their training. The author attributes this to inadequate training provided by TVET institutions, leading to a sense among graduates of being poorly prepared for the job market. Interviewing students and teachers, Harada et al. (2018), on the other hand, found that TVET education and certificates are seen as aligned with job market needs, particularly in hospitality and construction. Acknowledging outdated curricula, TVET teachers actively compensate with internet resources, and collaborating with teachers from other disciplines or institutions. The authors also found that TVET students prioritize practical and economic aspects, contrasting with university students who focus more on self-realization and societal contributions. Luangaphay and Vida (2023) explored how factors such as gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, and education influence employment status. With the help of a household survey, Chea and Huijsmans (2014) researched informal household-based apprenticeships and privately organized, commercial classroom-based training, and they found that these played an important role in the informal economy. However, despite these valuable insights, very few, if any, studies have explored the private sector’s perspective. This article aims to contribute to the existing literature in this area. While acknowledging that the study is limited to 144 companies in the formal sector, and primarily enables descriptive statistics rather complex causal analysis, we believe that giving voice to the manufacturing companies adds an important perspective to the ongoing discussion.

This article seeks to address the following research questions: What kind of growth and transformation can be observed in the manufacturing industry? What are the skills requirements and skills shortages perceived by employers? And what types of training programs or qualifications are preferred by the manufacturing industry in Lao PDR to enhance workforce skills?

Key findings from our research include:

- The manufacturing industry in Lao PDR has experienced a period of remarkable growth and transformation.

- Given the growth rates, and the outflow of labor to neighboring Thailand and within the country to extracting industries, it is surprising not to see more skills shortage reported.

- A reason could be that the industry has a long history of compensating a lack of education by upskilling, primarily through informal learning, workers that the companies hire at the factory gates.

- This would also explain why there is little difference between occupational levels with regard to skills shortages. Supervisors and technicians are internally promoted rather than externally recruited.

- The interviews confirmed that both production and HR managers prioritize hands-on skills and experience over education or qualifications when hiring.

- Companies seem to be reluctant to trust TVET qualifications—they do not find any difference between those with such qualifications and other workers, or are unable to access the few TVET graduates in the first place.

By examining these crucial aspects, this study sheds light on the intersection of TVET, manufacturing industries, and growth in Lao PDR, offering insights for policymakers, educators, and industry stakeholders alike.

2 Methodology

The study is part of a larger research program aiming to investigate the relationship between TVET and transformation and inclusive growth in manufacturing industries. In Lao PDR, the focus was on three industries: Garments, Food & Beverage, and others (cement, plastic product, assemble motorcycle). Three main sources were used for the study: a survey conducted in 2018 covering 144 companies; as well as 32 more detailed interviews with representatives of 16 companies, conducted in 2019. The companies are situated in Champasak, Khammuane, Luang Prabang, Savannakhet, Xayabury, Vientiane and Vientiane Province (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Provinces where company interviews took place (source: STEPMAP)

For the survey, lists of formally registered companies with 50 or more employees were created for each industry, and either the full population or a random sample was invited to participate. Because the number of large companies in Lao PDR is quite small, the threshold was later dropped to 25 employees or more. 144 companies were surveyed altogether: 54 garment companies, 44 food and beverage companies, and 46 companies from the remaining manufacturing sector. The survey covered areas such as skills shortages, formal training programs, employment numbers and trends, salaries and non-monetary compensation, changes in products, machines and technology, and sales and investments. The company interviews focused on how formal skills development programs affect work organization and technology use, and identified internal and external factors – such as industrial strategy, industrialization trajectory, and national vocational education – affecting these relationships. Furthermore, data on training uptake was collected. The interview sample was drawn from the companies participating in the survey; 16 companies were selected altogether (6 garment companies, 6 food and beverage companies and 4 other companies); care was taken to include both growing and non-growing companies. In each company, the production manager and human resources manager were interviewed. The survey and interview responses were analysed as a whole, but also separately for the individual industries as well as for five occupational levels, to identify patterns and trends in the data.

The occupational levels were defined as follows: General workers, as the name suggests, perform simple and routine physical or manual tasks. These workers are responsible for basic tasks that do not require specialized skills or knowledge. Operators, on the other hand, are responsible for operating machinery and electronic equipment. They are also responsible for maintenance and repair of electrical and mechanical equipment, as well as manipulation, ordering and storage of information. Operators typically require specialized knowledge and skills related to the equipment they operate. Supervisors, as a higher level of management, require an extensive body of factual and procedural knowledge. They have oversight of a group of operators and/or general workers and are responsible for ensuring that the work is performed according to established procedures and quality standards. Technicians are another specialized group of workers who typically perform complex technical and practical tasks. They require an extensive body of factual, technical, and procedural knowledge in a specialized field. These workers are responsible for tasks that require advanced technical knowledge and expertise; and the Higher management of the company consists of a group of high-level executives who actively participate in the daily supervision, planning, and administrative processes required by the establishment to help meet its objectives. These executives are responsible for setting the strategic direction of the company and ensuring that it operates efficiently and effectively.

One potential limitation, especially for the interviews, is the small sample size. The 16 companies and 32 respondents may not be representative of the entire manufacturing sector in Lao PDR, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The companies surveyed are part of the formal economy, while informality plays a large role in Lao PDR: the informal economy includes 73 % of non-agricultural employment. (According to the Labour Force Survey, this proportion has changed little between 2017 (75% informality) and 2023 (73%)) (ILOSTAT explorer n.d.). Additionally, the results could be skewed by the fact that only companies with at least 25 employees were sampled, which means that those that shrank in size below this threshold were not taken into consideration. Response biases may also be present, including recall bias (companies were asked to provide data for 2012 and 2017 while the survey and interviews were conducted in 2018 and 2019); social desirability or the desire to align figures with those reported to the authorities might also have played a part. Keeping such limitations in mind, and acknowledging that the results must be interpreted with the necessary caution, we believe that they still add value in a situation where there is sparse information to begin with.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Growth and transformation in the manufacturing industry

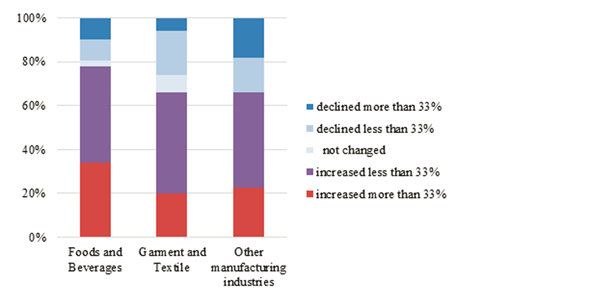

The survey results show that the manufacturing industry in Lao PDR has experienced a period of remarkable growth and transformation. Notably, the Food & Beverage (F&B) sector has witnessed rapid expansion (see Figure 2), primarily fuelled by domestic elements such as population growth, socio-economic advancement, and evolving consumer demands.

Figure 2: Industrial growth: Change in sales volume between 2012 and 2017 (Source: Survey of 144 companies)

The influence of these factors is evidenced by changes within individual businesses. A representative from a pizza company illustrates shifts in customer demand by pointing to the extension of their menu: “The company has increased its menu offerings from 15 to 21 and added sizes from M and L to S, M, and L.” A company from the salt manufacturing sub-industry points to the adoption of new technology which has led to increased productivity: “During the past 5 years we have increasingly used solar energy to dry the salt. This method is more comfortable and reduces the environmental impact as we’re not burning wood. We brought two salt processing machines from Vietnam in order to reduce working time and increase product quality.” Infrastructure expansion, such as the development of a high-speed train line, and building construction more broadly, has prompted the cement manufacturing industry to adapt. As one industry insider put it, “Mostly it is about technology but it also depends on customers. For example, in the past we only produced cement [type] 525 and 325, but now in the railway construction project, we have to produce cement 425 according to the demand of the customers.” Other companies point to strategic decisions made by management or owners: “In the past the factory … consisted of a rice mill section, slaughter section, marketing section, as well as a material and warehouse section. If we hold too many working functions, it will deteriorate the quality of final product, therefore the rice mill was eliminated from the factory.” Growth has been further encouraged by the increasing influx of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the agriculture sector, which serves as the backbone of the F&B industry. Overall agricultural output grew by 6.3% per year from 1991 to 2010, and by 5.7% from 2010 to 2019 (ADB 2021). However, alongside these developments, there are also challenges. The food processing sector, despite its growth, is hampered by labor productivity issues. Factors such as inadequate workforce equipment, high taxes, complex tax regulations, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of labor skills contribute to this challenge. This is mirrored in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ranking, which has seen a significant downturn: In 2019, Lao PDR was demoted to the 154th position, from 139th rank in 2015 (World Bank 2016; 2020).

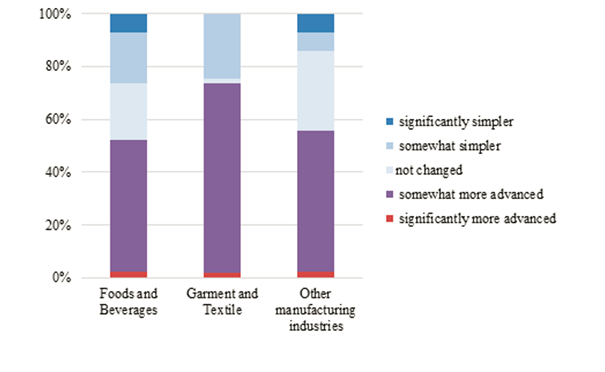

While it remains a major player within the Laotian economy, the garment industry’s growth has been stunted. In 2015, there were 92 garment factories, but in 2019 there were just 78 (Ramon Bruesseler 2021). Despite these obstacles, the garment industry has shown resilience and adaptability, and has undergone above-average transformation (see Figure 3), Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, garment factories fulfilling orders from overseas nations sought governmental approval to sustain their operations. The company diligently abided by the government’s disease control guidelines, ensuring a seamless response to customer requirements. Notably, the company rigorously adhered to the prescribed measures, successfully meeting its customer commitments. The survey and interviews show that the garment industry has embraced new technologies brought by foreign firms. Businesses have emphasized the delivery of high-quality products tailored to customers’ specifications, a strategy demonstrated by the rise in Cut-Make-Trim (CMT) manufacturing.

Finally, companies sought to improve productivity through on-the-job training and upskilling. Many garment companies realize that on-the-job training was useful (“Our company has provided on-the-job training for production personnel trained by supervisor, abroad training for supervisors, and training at the company by foreigner experts supported and financed by company”).

Figure 3: Industrial transformation: Change in technology and machinery between 2012 and 2017 (Source: Survey of 144 companies)

In conclusion, the rapid growth in the F&B sector and the substantial transformation in the garment industry illustrate the dynamic landscape of manufacturing in Lao PDR. These changes have been driven by diverse factors, each sector responding differently to various stimuli and challenges.

3.2 Skills shortage in the manufacturing industries but only when it comes to specific skill requirements

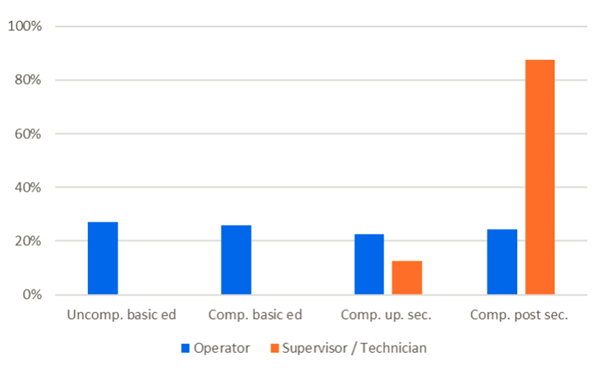

In Lao PDR, many manufacturing industries employed workers with low levels of education. Figure 4 depicts the distribution of employees with basic education, and those with diploma and higher education, across various job categories. Generally, within the operator workforce, there exists a diverse range of educational backgrounds. Approximately 28 % of factory operators possess only primary education, a trend particularly noticeable in small and medium-sized factories. These factories often recruit workers with lower educational qualifications and provide them with training to acquire various skills. Moreover, some factories also employ operators who have completed primary education, and their numbers are comparable to those without such qualifications. This is especially prevalent in garment factories, where a majority of operators are recruited from the pool of general workers, many of whom possess extensive experience. These experienced workers predominantly come from rural areas with limited access to education. On the other hand, technicians and supervisors typically have a higher level of education, with more than 80 % of them holding a high school diploma. Large factories, which offer competitive wages, tend to attract such candidates. A report by Homesana in 2019 sheds light on the demographic profile of female garment workers in Lao PDR. They are often young, unmarried migrants who have migrated from rural to urban areas and come from families engaged in low-income farming activities. These workers generally have minimal prior experience in waged employment, and their educational backgrounds tend to be modest.

Figure 4: Education of different occupation levels in the manufacturing industry. The categories are: uncompleted basic education, completed basic education (Year 9), completed upper secondary education (year 12), completed post-secondary/university education (year 12+). (Source: Survey of 144 companies)

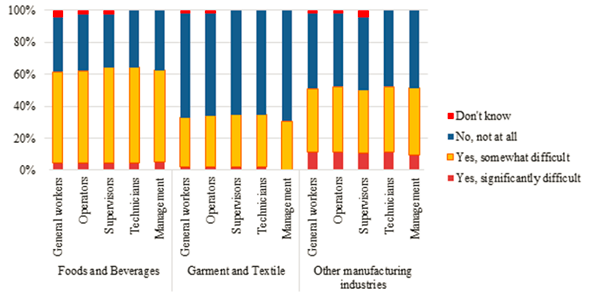

The company survey shows that about half of the companies indicate some difficulty of recruiting qualified employees (see Figure 5) but there are only a few companies indicating “significant difficulty”. There is little difference between the occupational levels, which is surprising; however, this might be a reflection of roles being filled internally rather than externally (see above). There are many distinct differences between the industries, however: F&B indicates significantly larger needs than garments, probably because of the higher growth rate. The remaining industries lie somewhat in between the Garment and F&B industries when it comes to difficulties. Interestingly, there is a larger proportion of companies indicating “significant difficulty,” which could indicate that some sub-sector ones experience more pronounced issues. Because of the small number of companies covered, this aspect cannot be explored further presently.

It is surprising that the rapid economic growth has not resulted in more pressing needs and challenges to fill positions. In addition to the economic growth, there is also the fact that the mining and hydropower sectors have seen much investment and have expanded accordingly, and are capable of paying higher salaries (Phouthonesy 2021). Finally, many Lao workers have migrated to Thailand. According to the Thai Labour Ministry, as of May 2019, there were 278,000 Lao workers registered in Thailand. One can safely surmise that the number is likely higher than this official figure because of the number of undocumented migrant workers (ILO 2020).

From the interviews, it is clear that both production and HR managers prioritize hands-on skills and experience over education or qualifications when hiring for production line roles, especially for positions like sewing machine operators. The managers expressed their willingness to consider applicants without any formal educational background or certifications, offering necessary on-the-job training when required. “Education background is not our main concern. We emphasize experience and skills for the positions that they apply for; however, for operator positions, we don’t specify any criteria on qualification, including whether the applicant must have completed high school. Instead, the applicant should have the ability to operate a sewing machine.” The garment industry workforce typically consists of individuals from rural areas with secondary education or less. Recognizing the potential in these individuals, firms arrange training programs for new hires to increase their experience and practical skills. However, when it comes to F&B and other industries the recruitment of employees for an operation with distinct attributes necessitates a certain educational threshold.

At the same time, there seem to be significant differences between sectors and also type of companies. Small factories are accustomed to not being able to access the few qualified graduates, and focus instead on upskilling workers themselves. Larger companies can be more selective. While Luangaphay and Vida (2023) reported that most companies believe that employees must hold a bachelor’s degree or above to be eligible for employment,it must be pointed out that their study focused on the capital Vientiane and seemed to include companies from all industries in the industry and service sector.

Figure 5: Skills shortage (“During the last 5 years, was it difficult to find employees for your establishment meeting your requirements?” (Source: Survey of 144 companies)

3.3 Contribution of vocational education and training to meeting the skills needs

In Lao PDR, much like other developing nations, the manufacturing industry often employs individuals with limited education, providing them with on-the-job training. This trend is driven by several factors. Primarily, Lao PDR’s labor market is characterized by a significant portion of the population having minimal education, resulting in an abundant pool of potential workers with lower qualifications. Manufacturers typically hire these individuals for roles not necessitating extensive education, such as entry-level or manual labor positions.

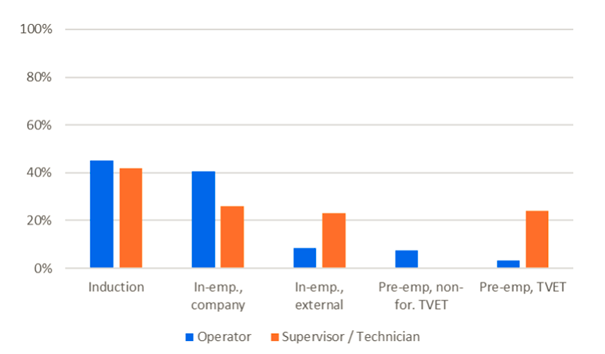

For other roles, companies address skills needs by providing induction, on-the-job, and upskilling training to workers. While pre-employment non-formal TVET training is almost non-existent for Supervisor/technician employees (see Fig. 6), some of it is available for operators. The latter group also benefits from greater opportunities for in-employment upskilling (in-employment training), that look like trend for the initial induction training for instance overview of the role and responsibilities, specific skills training and technical knowledge, mentoring or buddy system with experienced colleagues, on-the-job shadowing and observation: a majority of both operator and technician employees is undergoing this kind of training.

Figure 6: Training uptake in the manufacturing industries. The categories are: induction, in-employment training within the company, in-employment training outside the company, pre-employment TVET not leading to nationally recognized qualification, pre-employment TVET leading to nationally recognized qualification. (Source: Survey of 144 companies)

Limited access to higher education or specialized vocational training in some areas of Lao PDR, and outward migration of workers to Thailand, contributes to hiring trends, as discussed above. Keeping these factors in mind, it is still striking that most companies do not rely on the training provided by formal training providers, as illustrated by the small proportions of workers with pre-employment training.

Companies do not see their requirements being met currently: “Actually, we need mechanics with TVET knowledge and machinery working experience. Every year when we announce to look for new staff, I find many graduates [from technical colleges], but most of them don’t pass our standards. [They have] poor general knowledge, lower grades, poor English language skills, and are poor in soft skills. Thus we can’t get them”. Another company operating in plastic manufacturing found that non-qualified employees often performed better after learning the tasks in the companies (“There are two types [of employees]. They might be TVET graduates or graduates from a higher secondary school. We will take them to train. Some don’t have a certificate but they can do the work and improve themselves. Some people thought they have the knowledge, but when they come to work, they actually do not work well in our factory. Since 2010 we received lots of workers [from the technical colleges] but they are unsuccessful in our factory”). A third company sends their staff abroad because the knowledge required is too specialized (“It does not matter because there is no degree or course about cement production [in Lao PDR], we have to send our employees to train and study in China or Thailand. In Lao PDR, we only get people with degrees such as bachelor’s, master’s or PhD. They will be good in terms of ideas and leading, but regarding cement production they still need to learn more.”). Finally, other companies seem interested to recruit from TVET colleges, but they have difficulties attracting TVET graduates because they are too small (“um…we choose school education to work in administration office. In production line we need an undergone TVET but quite difficult to get them”) or have unattractive work conditions (“The factory needs TVET qualifications but most of the applicants didn’t like to work in our environment. There’s a strong smell inside the production line due to animal blood…”).

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, the study shows that many manufacturing companies in Lao PDR have experienced rapid growth and transformation. Some skills shortages are reported, but given the growth rates, and the outflow of labor to neighboring Thailand and within the country to the mining industries, it is surprising that this has not become more of a problem yet.

A reason could be that the manufacturing industry has a long history of training new workers to do specifically what is needed in their role, and not rely on training providers. Likewise, higher skills positions at the supervisor and technician level are filled by internally promoting workers rather than externally recruiting them. The interviews confirmed that both production and HR managers prioritize hands-on skills and experience over education or qualifications when hiring. As mentioned before, companies seem to be reluctant to trust TVET qualifications; they have not noticed any difference between workers who have such qualifications and those who do not, or they are not able to access the few TVET graduates in the first place. Significant skills shortages – which are currently only visible for certain profiles, and more strongly in “other industries” than in the F&B and garments industries (see Fig. 5) – might become more prevalent in the future, and start to impact growth and transformation eventually. Specifically, companies aiming to elevate their position in the value chains may find their technological “absorptive capacity” curbed if purely relying on upskilling themselves. There is also the issue that if companies invest in firm-specific skills only—due to the immediate utility of these skills, concerns about employee poaching, or workers relocating to Thailand—it might lead to an underinvestment of more general, transferable skills. While acknowledging that our results do not cover informal learning, it must be said that little training seems to be taking place. Interviewees highlighted several issues, such as small companies’ access to graduates and larger companies’ concerns about the quality and relevance of training.

While the results do not offer direct policy recommendations, they highlight challenges that necessitate further discussion and analysis. Effective solutions will likely require collaboration with companies, emphasizing the importance of including the private sector in these discussions. Fostering relationships across all levels, from policy discourse to practical cooperation with training providers, is essential.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who have contributed to this research. We are grateful to Dr. Sengprasong Phrakonkham, Nongkhane Phatthana, and Hannes Teutoburg-Weiss for their assistance with collection, analysis, and interpretation of data in Lao PDR specifically. Their expertise and input were instrumental in helping us draw meaningful conclusions from our findings. We would like to thank everyone who has given us comments to earlier versions, including the participants at the Fair Transition conference in Johannesburg in May 2023. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), through their joint research program “R4D”, under the call “Employment” (SNSF grant number 400340_194006). We are deeply grateful for the contributions of all those involved in this project, and any errors or omissions are entirely our own.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2021). Developing agriculture and tourism for inclusive growth in the LAO People’s Democratic Republic. Manila: ADB. Online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/732411/agriculture-tourism-inclusive-growth-lao-pdr.pdf (retrieved 23.11.2023).

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2022). Asian development bank member fact sheet. Manila: ADB. Online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/27776/lao-2021.pdf (retrieved 23.11.2023).

Bruesseler, R. (2021). Firm-Level Preparedness for the LDC Graduation in the Lao Garment Industry and Expected Loss of Preferential Market Access Conditions. Online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/Garment-Study-LaoPDR.pdf (23.11.2023).

Chea, L. & Huijsmans, R. (2014). Rural Internal Migrants Navigating Apprenticeships and Vocational Training: Insights from Cambodia and Lao PDR. In: Youthful Futures? Aspirations, Education and Employment in Asia (5-6 May 2014, Singapore). Online: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/51283/Metis_199498.pdf (retrieved 07.12.23).

Harada, A., Umemura, H., Atarashi, E., Morita, R., & Koizumi, Y. (2018). The Connection Between TVET and Labor Market in Lao PDR from the Perspective of Teachers’ and Students’ Experience at TVET and Other Post₋Secondary Education Institution. In: Working Paper Series in Study of “Knowledge Diplomacy” and Internationalization of Higher Education in Asia Project. Tokio: The University of Tokyo.

Homesana, C. (2019). Understanding the Urban Livelihoods and Wellbeing of Migrant Women Working in Garment Factories in Vientiane, Lao PDR. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2020). COVID-19: Impact on Migrant Workers and Country Response in Thailand. International Labour Organization Country Office for Thailand, Cambodia and Lao PDR. Online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-bangkok/documents/briefingnote/wcms_741920.pdf (retrieved 17.12.2023).

ILOSTAT explorer. (n.d.). SDG indicator 8.3.1 – Proportion of informal employment in total employment by sex and sector (%) Annual. Online: https://www.ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer19/?lang=en&id=SDG_0831_SEX_ECO_RT_A (retrieved 17.12.2023).

Leuang, V. (2016). Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and the National Economic Development of Lao PDR. Master Thesis. Seoul: Ewha Womans University Seuol.

Luangaphay, K. & Vida, V. (2023). The Analysis Of Educational Level Affecting On Employment In Vientiane Capital, Lao Pdr. In: CrossCultural Management Journal (1), 7–15.

Ministry of Education and Sports. (2020). Education and Sports Sector Development Plan 2021-2025. Vientiane: Ministry of Education and Sports.

Phouthonesy, P. (2021). The Lao PDR Country Report’. In Han, P. & Kimura, S. (eds.): Energy Outlook and Energy Saving Potential in East Asia 2020. Jakarta: ERIA.

UNESCO. (2020). TVET Country Profile Lao P.D.R. Paris: UNESCO. Online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/lao_tvet_country_profile.pdf (retrieved 23.11.2023).

World Bank. (2016). Doing Business 2016. Economy Profile Lao PDR. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank. (2020). Doing Business 2020. Economy Profile Lao PDR. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank. (2022). Lao PDR: Economic Recovery Challenged by Debt and Rising Prices. Washington D.C.: World Bank.