Abstract

Work-related Learning (WRL) is a learning form that is discussed in many countries around the world as a means to improve the quality of TVET-systems and thus learners’ competencies development. If WBL is included in an informal learning setting and is labor market oriented, the main principle of WBL is the interrelation between the two or even three learning venues, which are vocational schools, companies, and training centers. As a consequence of the relevance of WBL, there are different systematics and typologies such as work-geared learning and work-oriented learning attempting to classify learning forms according to the proximity to real work.

This article is based on the results from focus group discussions conducted during an International Research Workshop on Work-related Learning in February 2019 in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The workshop included practitioners and experts from Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna (RMUTL), Thailand, Technical University of Dortmund (TU Dortmund), Germany, and representative from Thai companies to discuss and exchange information and knowledge regarding Work-related Learning. Best practice examples of learning forms such as School-in-Factory (SIF) in Thailand and Production Schools or Learning Bay in Germany have been systematically studied and analyzed to find out about similarities, differences and problems in the implementation of Work-related Learning.

The workshop concluded that there are needs for didactical development and scientific research in vocational pedagogies in Thailand. Another important challenge is in the area of curricula design that merge the subject-orientation with the demand of work. Additionally, difference forms of learning that fit to the demand of learners were also pointed out in the workshop. To enhance quality of TVET and for further development of TVET-systems, it is necessary to continuously exchange knowledge between scientists and practitioners from different countries and to do research in TVET especially on Work-related Learning. Therefore, the results from this analysis are presented from the perspective of identifying additional research demand on WRL in Thailand.

Keywords: Work-related Learning, Technical and Vocational Education and Training, Learning in the process of work, Cooperation of learning venues

1 Framework and requirements for TVET in Thailand

Innovation in TVET-systems are complex challenges, which need to respect the given socio-economic context. The following chapter provides a basic insight into the current socio-economic context and the situation of the TVET-system in Thailand. Globalization has shown a significant impact not only towards socio-economic conditions, but also to the life of the people as well as to political affairs. With the drastic economic progress, that is a result of globalization, TVET plays an important role in ensuring the social and economic sustainability and prosperity of the country, especially during the times of disruptive technological progress (BIBB 2019).

1.1 Socio-economic conditions and demographic situation

Due to strong and rapid industrialization, Thailand’s entire social and economic structure has changed in recent years (Grosch 2018, 32). Thailand has been a “constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary form of government” since 1932 (iMove 2014, 10). The development of the Kingdom has progressed from an agrarian to an industrial and service society. Among various economic partners, Germany is one of the most important foreign trading partners to Thailand. With a gross domestic product of $ 345.7 billion (National Statistical Office Thailand 2019), Thailand is one of the advanced economies in Southeast Asia and has a well-developed infrastructure, a free economy and a general pro-investment regime. It has achieved steady growth through strong exports (iMove 2014, 11).

Thailand has 64.5 million inhabitants, 78% of whom are of Thai and 11 % of Chinese descent. Other ethnic groups are of Malay, Indian, Vietnamese and Cambodian descent. The predominant religion in Thailand is Buddhism. Moreover, Thailand has a young age average of 34.7 years and an official unemployment rate of around 1% (National Statistical Office Thailand 2019), which is one of the lowest rates in the world (Grosch 2018, 32). Furthermore, there are about 2.5 million foreign workers from neighbouring countries. Thailand is an attractive country for migrant workers. Since January 2013, there is a newly introduced minimum wage in Thailand. The aim is to increase purchasing power in Thailand and encourage companies to invest in better equipment and training for their employees (iMove 2014, 11).

Due to its strong industrialization process and specific demography, Thailand also has a growing demand for suitable and qualified skilled workers. In addition, cooperation between educational institute and the private sector should be developed better in order to adapt training content to the needs of the labour market (OVEC 2008, 2). Currently, the content that is taught in the training is not demand driven. At the same time, Thailand Industry 4.0 aims to develop an innovation-driven economy that will be on par with high-income countries. The continuous labor market development is one factor that will help drive such growth. In order to develop a competitive workforce, the Thai Government recognized the significant role of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and encouraged its improvement through various strategic policies in order to develop a competitive workforce. The implementation of these policies pose numerous challenges for the country, especially in the area of human resource development (Gennrich 2017). Similarly, increasing technology will fundamentally change work processes. As a result, collaboration between stakeholder groups is becoming increasingly important for identifying needs and training relevant professionals.

1.2 Situation of TVET in Thailand

Formal education in Thailand comprises of basic education (Pre-primary education, Primary education, Lower secondary education, and Upper secondary-general education), TVET and higher education (Phalasoon 2017, 2). It is managed at three different levels:

− the central level,

− the sub-national level, and

− the institutional level (Grosch 2018, 44).

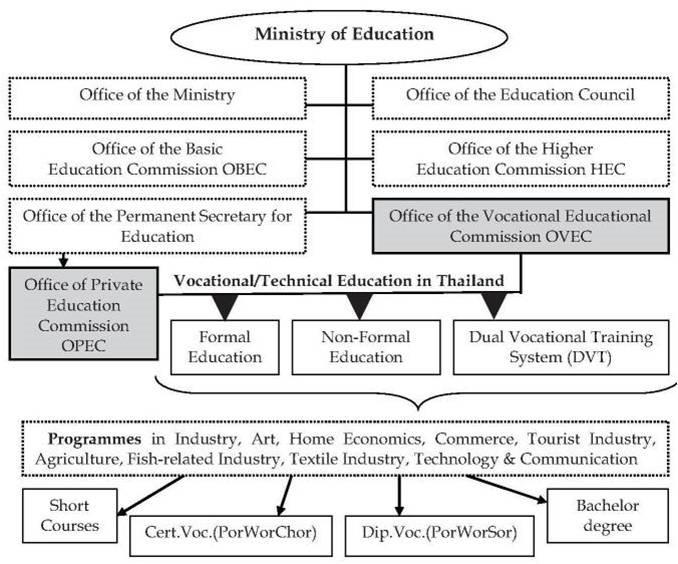

The Thai Ministry of Education (MOE) is in charge of all sectors of formal education and TVET. It is divided into various subdivisions, called Offices. The main responsible body for TVET is the Office of Vocational Education Commission (OVEC). In 2019, the Office of Higher Education (OHEC) has become a new Ministry of Higher Education. The detailed information about TVET within Ministry of Education in Thailand is illustrated in the graphic below.

Figure1: Organizational chart of Thai Technical and Vocational Education (Chupradit & Baron-Gutty 2009, 61)

Since 2008, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) has been regulated by the National TVET Act. TVET can be obtained in a variety of ways, mostly in what are commonly referred to as Technical and Vocational Colleges:

− Formal Vocational Education. Formal Vocational Education consists of two different three-year full-time study programs: the “Certificate Vocational” (PorWorChor), and the “Diploma Vocational” (PorWorSor) (Grosch 2018, 64). According to the Student statistics summary Academic Year 2019, there are approximately 1,012,580 students enrolled in the formal Vocational education (including students from PorWorChor and PorWorSor programmes) (Information Technology and Vocational Manpower Center, OVEC 2019).

− Non-formal Vocational Training. The programmes are more flexible. “The curricular, period of time, course evaluation are set into certain conditions according to the needs of targeted groups” (Chupradit & Baron-Gutty 2009, 61). Certificate is acquired after completing the training.

− Dual Vocational Training System / Apprenticeship. The “Certificate in Dual Education” is acquired for different level of training programmes. In 2015, there were 91,448 students in total who were trained in the DVT system. (Dual Vocational Education Center, OVEC 2019).

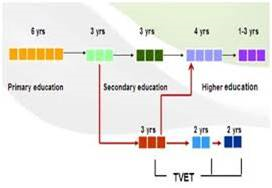

Figure 2: Formal Vocational and Training System in Thailand (Researching Virtual Initiatives in Education 2014)

Basic education constitutes of six years of elementary school, three years of lower secondary school and three more years of upper secondary school. After completing three years of lower secondary education, there are two possible pathways to continue the upper secondary education: general education and TVET. The upper secondary- general education (3 years) is offered to develop learners with regard to their aptitude, interest, potential and special talents as a basis for higher education. The upper secondary- vocational education (in Thai: PorWorChor) is designed to develop learners’ knowledge and skills in careers to be skilled labor force or to continue study in a higher professional level (Ministry of Education- Thailand 2016, 1). For further education, learners can continue on their respective stream of education that is from upper secondary- general education toward academic undergraduate and from upper secondary- vocational education toward diploma vocational level (also known in Thai as PorWorSor). This PorWorSor programme is usually completed in two years. However, it is also possible for learners from the upper secondary- general education to apply for TVET at diploma vocational level. Additionally, learners from TVET will continue two more years to achieve the bachelor of technology.

TVET in Thailand is based on the prevailing market conditions. The aim is to impart professional knowledge into occupations. The curricula of TVET depends on the occupational field, the provider and the respective mode of implementation (iMove 2014). In the end, the students have to pass a national examination, the so-called Vocational National Education Test, which is administered by The National Institute of Educational Testing Service (NIETS 2019).

The Dual Vocational Training (DVT) was introduced in 1988 (B.E. 2531) (Office of the Official Information Commission, Thailand 2013) and informed by the German model. The training courses, which are organized in full-time programs in vocational colleges, also provide internships in companies (Grosch 2018, 77). In DVT, learning takes place in college and in the workplace, with practice sessions taking place either at weekly intervals or within the semester. However, the teaching staff is often poorly trained, and the workshops of the schools are often equipped with outdated machines (ibid.).

In the in-company workplace too, learning predominantly takes place by imitation, because the trainers in the companies have no pedagogical qualifications (Grosch 2018, 77). To counteract this, the Thai government has been trying to support the cooperation between vocational colleges and private companies through various plans, for example the 15 years Implementation Guideline for the Office of Vocational Education Commission: Strategic policy on the development of vocational manpower 2012-2016. However, this has not been successfully implemented (Phalasoon 2017).

There are about 900 private and public institutions offering vocational training programs and about 1.05 million students in the formal education system (as of 2012) (Australian Education International 2013). However, TVET in Thailand is oriented towards academic disciplines or branches of industry and does not include the principle of vocations and its work processes as it does in Germany (ibid., 71).

The demand for qualified skilled workers in Thailand is steadily increasing. Nevertheless, the quality of training has not yet been adequately adapted and accommodated to this demand. Rising wage costs led to a so-called “middle income trap” (Grosch 2018, 71). Based on competitiveness and demand, reform approaches promote “the initiatives which include pathway concepts through recognition of prior learning approaches, professional development for technical teachers to underpin competency approaches, and the improvement of the profile and parental perceptions of vocational education” (Australian Education International 2013, 22). Increasing and intensified cooperation between companies and groups of professional (such as Chamber of Crafts) is intended to increase the existing quality of training.

Moreover, the OVEC and the state have developed guidelines to introduce high quality employment standards. The Thailand Professional Qualification Institute is responsible for checking and monitoring these standards.

In general, there is a lower appreciation of vocational education in Thailand. This difference in appreciation of mental and physical work is due to cultural aspects prevalent in the country (Grosch 2018, 72). This is apparent, e.g. clearly in the number of learners who move to secondary education which is generally higher than in the vocational schools. The strong conservatism limits the implementation of innovations, especially in the field of education. The flow of information is still hierarchical in Thailand and is controlled accordingly.

2 The in-company workplace as a venue for experiential competence development

The following chapter will describe different typology of Work-related Learning as well as related didactical requirements, educational regulations, and best practice examples for learning and competence promoting forms of learning.

The place of work as a place of learning becomes increasingly important. “In the company, self-directed and experiential learning is promoted in the process of work, and more strongly linked to organized learning” (Dehnbostel 2019, 6). By learning at the workplace, especially from a business perspective, work processes should be improved and optimized in order to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the work (ibid.). Thus learning and working must be linked together, but this approach requires an adequate didactic conception.

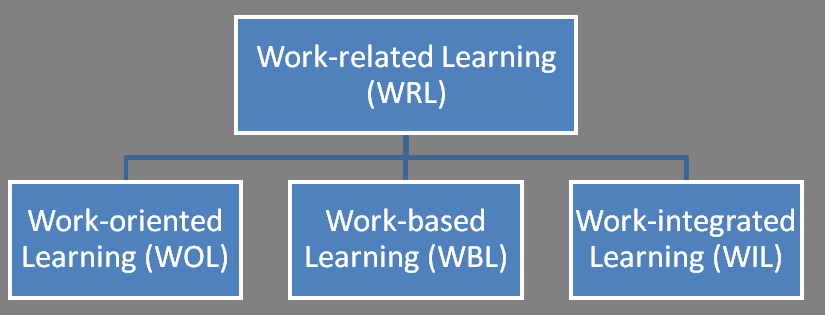

Figure 3: Typology of Work-related Learning (adapted from Dehnbostel & Schröder 2017)

The concept of Work-related Learning (WRL) takes an important role. “The term Work-related Learning refers to learning in enterprises, training centers, schools and academia. This includes learning at work and learning within work process and through work” (Dehnbostel & Schröder 2017, 1). By considering the relationship between place of learning and place of work, three different types of Work-related Learning can be identified. They are Work-oriented Learning, Work-based Learning and Work-integrated Learning. By combining the formal and informal forms of learning that are based on experiential learning, this can contribute to learners’ competence development.

− Work-oriented Learning (WOL): “WOL takes place in formal learning venues. Learning is made up of simulation of work organization, work tasks and processes” (Dehnbostel & Schröder 2017, 5). This learning form is often used at vocational schools and training centers. Some of the examples are production school and junior company.

− Work-based Learning (WBL): Originally termed as Work-connected Learning. Learning venue and workplace are separated. However, in terms of work organization they are connected. It is usually takes place at the workplace. Examples are school in factory and student company.

− Work-integrated Learning (WIL): Learning venue and workplace are identical: the actual learning takes place at the workplace or in the work process (Dehnbostel & Schröder 2017, 5). Good examples of this learning form are learning bay and job rotation.

The aim of the different forms of work-related learning is the development of appropriate skills. For having good occupational skills, an adequate theoretical knowledge and experience are necessary. They have to be combined and reflected. In addition to the practice, the teaching of theoretical knowledge takes place parallel to the work in the vocational schools. This organized educational learning, which pursues specific learning goals, is also referred to as formal learning.

In contrast to this is informal learning, which according to Dehnbostel has been recognized as a part of occupational learning. Informal learning is characterized by self-determined, semi-conscious learning, which is based on experience (Rohs & Dehnbostel 2007, 1-2). Thus, there are existing interfaces with forms of learning that have both formal and informal learning characteristics. Formal and informal learning are interlinked and co-dependent on each other mutually (ibid., 1).

In education and training, informal learning has become more important against the background of changing competence requirements. Thus, the necessary experience for complex work tasks can only be acquired directly in the work process (ibid., 2).

There are many advantages for learning in the process of work. “The work process-oriented teaching and learning in the dual system provides young people with an opportunity to acquire specialist skills, knowledge and abilities, in addition to personal competences, through exposure to professional experiences at the workplace” (Gennrich 2017, 4). The further development of professional skills is required to remain competitive and to maintain a job. “Dual or workplace-based training is not outdated, but rather strongly needed to fill the gap of well-qualified workforces with target-related technological qualifications and work experience” (ibid., 6).

2.1 Didactical requirements

To ensure that the place of work is suitable for learning and produces the best learning outcome, the quality of a workplace as a place of learning is significant. It is important to recognize learning in the process of work as this lead to competence development while maintaining his employment status. Furthermore, the quality of workplace has to be considered as an important factor contributing to lifelong learning that will benefit society at large (Dehnbostel 2019). Additionally, it can also be counted as an economic factor, particularly in the competitiveness of a company.

Since learning occurs in the workplace, different dimensions should be taken into account when assessing the learning support of the workplace. According to Dehnbostel (2019), the following elements must be considered:

− Complete action/project orientation: confront employees with tasks that require many “action operations”. Holistic work action and self-directed learning of the individual are thus supported (Dehnbostel 2019, 66).

− Freedom of action: The employee should have the opportunity in the work process to “act appropriately, purposefully and independently” (ibid.).

− Problem orientation and complexity experience: This dimension relates to the complexity and scope of a given task. If these become higher and the task becomes more extensive, the problem and complexity experience of the employee also increases (ibid.).

− Social support: interaction and communication play an enormous role in the work process and should not be neglected. However, these also depend on the particular culture that prevails in the company. Through group work, “learning turns from an individual to a collective process” (ibid.).

− Individual development: this is the orientation of the respective task, which is placed on the individual. It should neither be over-demanding nor under-demanding (ibid., 67).

− Development of professionalism: individuals who are involved in the work process benefit from increased professionalism in their careers. Moreover, “feedback and experience constantly improve the professional ability to act and the expertise of the individual” (ibid.).

− Reflexivity: “Reflectivity is about reflecting on work structures and environments as well as oneself. Reflexivity means the conscious, critical and responsible assessment of actions based on experience and knowledge “(ibid.).

The successful implementation of learning at the workplace relies not only to the quality of workplace and learning support but also depends on the training regulations, as in the case of Germany. The following section will briefly provide information about different learning venues for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Germany.

2.2 Three different places of learning in Germany

There are three different locations for learning in TVET in Germany, namely vocational school, workplace and training center.

2.2.1 Vocational school

Vocational school is included in two different forms of vocational trainings; in the dual system and in the full-time learning in vocational school.

In the dual training, roles of vocational school are to provide learners with basic and specialized vocational training and to extend prior knowledge in general education. The teaching is allocated in cooperation with other relevant bodies, such as training centers and industrial partners. While the duties of vocational school in full-time learning at vocational school are to introduce students to one or more occupations and train them for those occupations (Schneider et al. 2007).

2.2.2 Workplace as place of learning

In Germany, training places are also offered in the workplace. Companies enter into a contract with trainees. To enhance trainees’ professional competence, these companies are responsible for providing trainers to train the employees with relevant educational or skill courses.

For the dual vocational training, the company provides in-company training to learners (approx. three to four days per week depending on the occupation) and makes sure that the training courses are relevant to the training directive and a framework curriculum.

2.2.3 Training center

Some of the small and medium enterprises do not have enough specialized trainers to cover all of the content in the training courses, lack suitable training equipment, etc. Therefore, the training center is designed to supplement in-company training.

2.3 Learning and competence-promoting forms of learning

In Germany, there are forms of learning that promote experiential learning in the work process. Good examples are the production school and the learning bay. In these two examples, the learning places are optimally linked and also well established and successful implemented. They are explained in more detail below.

2.3.1 Production school:

According to Mertens “the pedagogical concept of the production school is a constitutive part of the work and production processes for the promotion and competence development of young people. Learning processes are purposefully linked with work in structures close to the company with tools and contents. This is precisely what develops and promotes the knowledge, skills and behaviors necessary to start and carry out vocational training” (Mertens & Stang 2016, 1).

Besides the social view, production schools also have an economic perspective to provide a return on investment. Therefore, young people learn by creating marketable products. However, production schools attach particular importance to their own experience of effectiveness and the self-motivation of the learners. Therefore, production schools are a good example of work-based learning, as informal learning takes place in an institutionalized setting.

The production schools in Germany originated at the beginning of the nineties, inspired by the Danish production schools. Currently there are about 200 production schools in Germany with 7,500 places for apprentices per year. Despite the similarities between Germany and Denmark, the production schools in Germany are not unified.

2.3.2 Learning bay:

In the aftermath of the 3rd industrial revolution, which triggered significant changes in information and communication technologies, there is an increased demand in the workplace for learning forms that directly connect learning and work.

The learning bay, as one approach of combining learning and working, directly connects learning opportunity to the work process. The learning bay is a sub-department of the production line at the center of company work processes (for example in the car industry), in which learners work independently or in groups on real or digital products. This learning form ensures a high practical orientation. Learners have more time to explore the learning objects and the learning processes are supported by facilitators who are well-resourced with occupational, methodological and didactical knowledge (Forschungsinstitut Betriebliche Bildung 2019).

Moreover, the learning bay can contribute to the improvement of learning processes and to the learning ability of individuals and social groups. If they are involved in vocational training, a higher quality work can be achieved. The willingness to learn and the learning ability of the learners are directly increased. Using the workplace as a venue for learning intents to link learning and working together to develop experiential competence. To ensure this form of learning, didactical requirements for learning in the process of work such as a complete action oriented is one of the substantial factors. The training regulation that states roles and responsibilities of each party involved is to guarantee that the training framework is up-to-date and relevant to the demand of labor market. Production school and learning bay are the two examples provided in this article to demonstrate the forms of learning that promote competence in Germany.

2.3.3 Work- and Learning Tasks

Work- and Learning Tasks (WLT) were developed and implemented in the Advanced IT Training System in Germany, where informal forms of learning prevail. WLT are being employed in fluid work-processes and aim at the enhancement of selected competences (Schröder 2009). WLTs are based on real in-company work tasks, which must fulfil certain criteria such as a certain degree of complexity, identity and uniqueness. The learner is given the chance to anticipate the work process with respect to a final objective or product. Deviation from the original planning forms the basis for reflection and learning.

From these examples, it could be seen that Germany has a long-standing history of research on Work-related Learning. These examples were employed at all relevant learning venues of TVET and therefore might be regarded as a benchmark system. Nevertheless, there are forms of WRL in Thailand, which proof to be innovative in the context of Thailand.

3 Example of established forms of Work-related Learning in Thailand

3.1 School-in-Factory (SIF)

The School-in-Factory (SIF) is a form of learning that provides learning opportunities for TVET in different learning venues. SIF is the result of collaboration between the Office of National Higher Education Science Research and Innovation Policy Council (former National Science Technology and Innovation Policy Office – STI), Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna (RMUTL) and Michelin Siam Company Limited. The respective stakeholders make different contributions to this program. RMUTL supports by offering the facilitators and lecturers and the Michelin Company provides the place of work or the in-company learning venue (Phalasoon 2017, 8). The STI supports the program as a state cooperation partner.

School-in-Factory (SIF) is one of the best practice examples for Work-related Learning in Thailand. The aims are to better qualify skilled workers, to decrease the lack of qualified engineers and research engineers, and to reduce staff turnover, thus improving the productivity of the country (ibid.).

The School-in-Factory started for the first time in 2012. It is a program that has a duration of two years. In every year, the learners spend three months at the university and work nine months in the factory or company. However, these learners have a different educational background. There are learners with a lower secondary school degree or learners with a vocational certificate. Because of this diversity, the students have to undergo a two-month training program before being included in the SIF (Phalasoon 2017, 8).

The course of work in the company is structured as follows: The learners have 3-4 hours of theoretical lessons every day in the factory and 8 hours of work for 6 days a week. Therefore, the theoretical knowledge and the work tasks are well aligned with each together. Learning in the work process should be encouraged in this way. In addition, once a month the learners present their own learning progress to the teachers and facilitators and are thus also reflecting on their learning progress (ibid.).

Overall, SIF encourages learning in the process of work. Therefore, as a representative of Work-Related Learning, SIF’s success is proof of the benefits of implementing Dual TVET in Thailand.

3.2 Tripartite TVET System: cooperation among University, Vocational School and Company

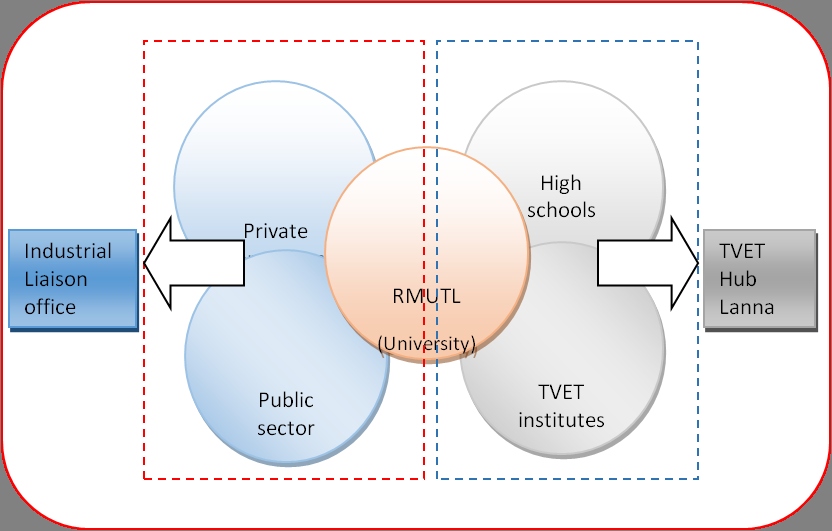

The School-in-Factory project was implemented as an initiative from RMUTL to develop another possible solution to solve the problem of lacking skilled labor in Thailand. The project later evolved to include a few more private partner companies such as Betagro, Bio Story Group and Benya Tractor. In addition, the RMUTL has become a significant player in sharing the knowledge acquired from this project with other TVET institutes. RMUTL and TVET schools collaborate through teacher training and joint project. Hence, TVET schools are here the implementation unit of this education program. The graphic below shows the cooperation among different stakeholders.

Figure 3: Tripartite TVET System (adapted from Moonpa 2019)

Figure 3: Tripartite TVET System (adapted from Moonpa 2019)

This Tripartite TVET System is operated by two main bodies. On the one hand, the Industrial Liaison Office is responsible for the cooperation among public sector, private companies and university. Its main tasks are managing financial support, Talent Mobility Project and several other projects like Betagro WIL TVET Academy Project and SIF: Star Holding Group. On the other hand, the Lanna Technical and Vocational Education and Training Hub (TVET Hub Lanna) coordinates among university, high school and TVET colleges. The major duties of TVET Hub are administrative work and academic work, such as executive committee meeting, financial management, training projects and Fabrication Lab. From Figure 4, it can be seen that the university is playing an important role in doing action research in TVET education and coordinating with its partners. Therefore, Tripartite TVET system supports for the implementation of the Dual TVET System in Thailand.

4 Findings and recommendations

The international research workshop on Work-related Learning provided some thoughtful insights that are summarized in this chapter. The three-day workshop was organized at RMUTL with totally 25 participants from different level of experiences and background. These participants were mainly teachers, lecturers, researchers in TVET areas, and observers from the private companies. The main objectives of the group discussion were to discuss and exchange ideas regarding “concepts of TVET”, “learning facilitator”, “comparison of didactical approaches”, and “different learning forms in Thailand” which were documented by researchers from TU Dortmund. The following conclusions show the central issues/questions for the improvement of the TVET system in Thailand.

− Interviews of teachers and students from School-in-Factory (SIF) project revealed that “students show better working results compared to regular employees because they are motivated to study in an authentic learning environment” (Phalasoon 2017, 9). Nevertheless, the training duration should be adapted to create a suitable learning environment.

− SIF is a way to design experiential learning in the work process. However, teachers involved in this project reported that the ability to study and concentrate is limited for many students. Questions discussed included how to increase students’ motivation by using other learning forms and how to design the learning task that link to the work task ware raised. There was also a need to consider individualized forms of learning that are adaptable to the different levels of students’ knowledge.

− It is also shown that this form of learning yields better outcome if there are enough teachers and facilitators to take care of, as well as to transfer their expertise and experiences, to these learners. However, the most important issues were about the specific roles and responsibilities of teachers, lecturers and facilitators.

− Regarding the qualifications of in-company trainers, Germany has shown a well-defined and concrete structure about the trainers’ duties and how they should be produced. In-company training staff who are provided by the company and are personally and technically qualified bear the responsibility for providing the training content in the respective occupations according to § 28 Vocational Training Act trainees (The Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training 2019).

− For learning in the process of work, there need to be several dimensions fulfilled to receive the best learning outcome. The School-in-Factory concept already has some dimensions for the learning support. Thus, the dimensions of complete action, reflexivity and the development of professionalism can be rediscovered. These starting points should be further developed and complemented by the other dimensions in order to strengthen both the learning support in the workplace and the workplace as a place of learning.

For further research, the workshop concluded that it is necessary to conduct research about work process analysis, work process documentation and as well as career research. This task should be developed in further international TVET research.

5 Summary and Outlook

Thailand is in the middle of a transition from an agrarian to an industrial society. The biggest challenge is the modernization of the education system. Dual vocational training plays the key role to meet the threat of a shortage of skilled labor and to live up to the conditions of the labor market. For the implementation of these, however, a “cooperation culture” between vocational schools and companies must emerge in order to be able to implement dual training settings. In addition, qualified trainers are needed for the implementation. As concluded in the focus group discussion, Thai TVET teachers need pedagogical improvement. There is also a strong demand for scientific research in vocational pedagogy. Moreover, the question of establishing TVET as a self-reliant academic discipline in Thailand is seen as another possible solution.

TVET research finds itself in Thailand only in a very weakly developed form (see Grosch 2018, 91). “The resulting lack of knowledge is one of the main weaknesses of the TVET system and a key reason for its slow quality development” (Grosch 2018, 91). In his essay, Gennrich (2017) has well summarized the most concise recommendations that fit into this context. The three most important are the following:

− “Bridging the gap between the world of work and the world of education by promoting Dual Vocational Education and Training (DVET) and various other types of experienced vocational learning systems (such as WIL, etc.)” (Gennrich 2017, 8).

− “New investments in the business sector also need new investments in vocational education and the labour market sector focused on Industry 4.0” (Gennrich 2017, 9). As mentioned by Rukkiatwong (2016) that Thai vocational education is severely lacking in resources, particularly qualified teachers and training equipment.

− “Government institutions (MoE/OVEC/MHESI) should collaborate with leading companies and universities” (Gennrich 2017, 9).

With Thailand 4.0, the impact of globalization and evolving technology has contributed to the transformation of Thailand’s economic structure. Accordingly, the vocational education and training of teaching staff needs to be adapted. This could “narrow the gap between the high expectations of the industries and the current performance of education and training” (Gennrich 2017). TVET has to be more geared to the needs of the labour market.

References

Australian Education International (2013). Thailand Regulatory Fact Sheet. Online: https://internationaleducation.gov.au/International-network/thailand/Publications/Documents/AEI%20Thailand%20Fact%20Sheet%20March%202014%20Updates%20Word%20Version%20(2).pdf (retrieved 09.10.2019).

Chupradit, S., & Baron-Gutty, A. (2009). Education, Economy and Identity: Vocational and cooperative education in Thailand: A presentation: Institut de recherche sur l’Asie du Sud-Est contemporaine. Online: https://books.google.de/books?id=KztjDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (retrieved 12.07.2019).

Dehnbostel, P. (2019). Lernen im Arbeitsprozess – Grundlagen und Entwicklungsperspektiven: Betriebliche Lernen und berufliche Kompetenzentwicklung. (2019). Hagen: FernUniversitaet Hagen.

Dehnbostel, P. & Schroeder, T. (2017). Work based and work related learning. Models and learning concepts. In: TVET@Asia. Issue 9, 1-11. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/9/issues/issue9/dehnbostel-schroeder-tvet9. (retrieved 25.04.2019).

Dual Vocational Education Center, OVEC (2019). Number of Dual Vocational training students classified by subject, 2015. Online: http://dvec.vec.go.th/th-th.aspx (retrieved 26.11.2019).

Forschungsinstitut Betriebliche Bildung (2019). Lernen in Lerninseln: Qualifizieren im Betrieb. Online: http://qib.f-bb.de/mediadb/3521/10212/Lerninseln.pdf (retrieved 25.09.2019).

Gennrich, R. (2017). Moving Across the Middle Income Trap (MIT) Border through Human Capacity Building. Thailand 4.0. Industry 4.0 Emerging Challenges for Vocational Education and Training. In: TVET@Asia. Issue 8, 1-16. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue/8/gennrich. (retrieved 15.05.2019).

Grosch, M. (2018). Internationales Handbuch der Berufsbildung. Thailand.

IMOVE (2014). Marktstudie Thailand. Für den Export beruflicher Aus- und Weiterbildung. Online: https://www.imove-germany.de/cps/rde/xbcr/imove_projekt_de/d_iMOVE-Marktstudie_Thailand_2014.pdf (retrieved 25.04.2019).

Information Technology and Vocational Manpower Center, Office of the Vocational Education Commission (2019). Student statistics summary Academic Year 2019. Online: http://techno.vec.go.th/tabid/766/ArticleId/24892/language/th-TH/-2562-1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12-13-14-15-16-17-18.aspx (retrieved 26.11.2019).

Mertens, M., & Stang, H. (2016). Produktionsschulen in Deutschland. Online: https://www.jugendhilfeportal.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fkp_quelle/pdf/16_06_24-Mertens_Stang_PS_in_Deutschland_%C3%9CA.pdf (retrieved 08.08.2019).

Ministry of Education. 2016 Educational Statistics. Bangkok, Thailand. Online: http://www.en.moe.go.th/enMoe2017/images/PDF/statistics2559.pdf (retrieved 26.11.2019).

Moonpa, N. (2019). Tri-education System and Work-integrated Learning. Paper presented to The 10th Rajamangala University of Technology International Conference, Chiangmai, Thailand, July 24-26, 2019.

National Statistical Office Thailand (2019). Key indicators: Unemployment rate and the growth rate of GDP. Online: http://www.nso.go.th/sites/2014en (retrieved 05.07.2019).

Office of the Official Information Commission, Thailand (2013). History and background of the Vocational Education Commission. Online: http://www.oic.go.th/web2017/main_.html (retrieved 27.11.2019).

Office of the Vocational Education Commission (2008). Vocational Education Act of B.E. 2551 (2008). Thailand.

Phalasoon, S. (2017). School in Factory (SIF). An Approach of Work-integrated Learning in Thailand. In: TVET@Asia. Issue 9. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/test-issue-9/issues/issue9/test-article-2-issue-9. (retrieved 15.05.2019).

Researching Virtual Initiatives in Education (2014). Thailand: Vocational Education. Online: http://www.virtualschoolsandcolleges.eu/index.php/Thailand (retrieved on 18.09.2019).

Rohs, M., & Dehnbostel, P. (2007). Informelles Lernen in der betrieblich-beruflichen Weiterbildung, 1–4. Online: https://archive.org/details/RohsM.DehnbostelP.2007.InformellesLernenInDer/page/n3 (retrieved 08.08.2019).

Rukkiatwong, N. (2016). Vocational Training reform in Thailand. Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) Online: https://tdri.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/nuthasid-vocational-education-v02_2.pdf (retrieved 26.09.2019).

Schneider, U., Krause, M., & Woll, C. (2007). Vocational education and training in Germany: Short description. Online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5173_en.pdf (retrieved 02.12.2019).

Schröder, T. (2008): Arbeits- und Lernaufgaben für die Weiterbildung. Eine Lernform für das Lernen im Prozess der Arbeit. Bertelsmann.

The Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (2019). Vocational education and training for “Thailand 4.0”. Online: https://www.bibb.de/en/62647.php (retrieved 18.09.2019).

The Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (2019). Betriebliches Ausbildungspersonal. Online: https://www.bibb.de/de/8606.php. (retrieved 25.04.2019).

The National Institute of Educational Testing Service (2019). V-NET: Vocational National Educational Test. Online: https://www.niets.or.th/en/catalog/view/2222 (retrieved 26.11.2019)

Citation

Moonpa, N., Phalasoon, S., Gulich, J., & Beecker, P. (2019). Approaches and Structures of Work-related Learning in TVET in Thailand. In: TVET@Asia, issue 13, 1-19. Online: https://tvet-online.asia/issue/13/phalasoon-et-al/ (retrieved 30.06.2019).