Abstract

The concept of transferable skills has only recently been introduced in Japan. While elements contained in the concept of transferable skills are not entirely new, efforts to package them, design and implement them in a systematic way are relatively new. In addition, a clear and common understanding of the concept itself, as well as a coherent implementation strategy that is agreed on by stakeholders, is yet to be developed. This article introduces recent discussions on transferable skills in the policy arena, presents some examples of policy implementation, a private initiative and the practice of a public specialized high school, and summarizes key findings and presents implications for policy and practice.

1 Introduction

Skills development is a priority concern in all countries to meet constantly changing economic and social needs, especially in the midst of today’s globalized world. Acquisition and development of transferable skills is increasingly emphasized in both industrial and educational (and training) domains. Employability of youth graduating from schools, training and higher education institutions has also been high on the agenda of international development (UNESCO 2012, World Bank 2012). Efforts are being made by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to develop instruments for the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO), including transferable skills and discipline-specific skills. Once established, this will enable international comparative assessment of student performance across diverse cultures, languages and different types of higher education institutions. In Japan, the government, industry and academia are all joining hands in devising a framework for collaboration in developing human resources that can work in today’s globalized knowledge economy and who are equipped with transferable skills. However, these are all taking place in the absence of an agreed concept of transferable skills. At best, current concepts are vague, and the best way forward to further develop them is not well known, including the context, situations, and methods of imparting them.

This article presents conceptual discussions, policies and initial efforts of practices on advancing the development of transferable skills in Japan, together with some implications and challenges ahead for policies and practices.

2 Transferable skills in national policies

2.1 Ministerial policies on transferable skills

Skills development has certainly been the core of Japan’s development policies both in government and the private sector. For a long time, Japan has been emphasizing the importance of human resource development for a country with limited natural resources. Indeed, the idea that the strength of the Japanese economy owes a lot to its competitive manufacturing sector is widely supported in Japan. The academia, the industry and the government of Japan have been working together to better understand the mechanisms with which Japanese leading industries advance innovation and productivity and have formulated relevant policies on human resources development.

The combination of tacit knowledge, or anmokuchi in Japanese, and explicit knowledge has been said to be the source of strength in Japanese firms. According to Nonaka, et al., the Western traditions of business management take knowledge as being explicit that is “transmittable in formal, systematic language” whereas Japanese firms typically view knowledge as being tacit that is “highly personal and hard to formalize, making it difficult to communicate to others” (Nonaka, et al. 1996, 834). They studied cases of Japanese firms and tried to explain how the explicit and tacit knowledge interact and create knowledge. Masuda (2007) maintains that the basic strategy of Japanese manufacturing firms lies in (1) a huge industrial, technological and technical stock at home and in companies (2) identification of producers and users, (3) field-orientation and field-based problem solving, (4) respecting multi-skilled workers, (5) emphasis on teamwork, unity and belonging, and (6) zeal for producing better goods (Masuda, 2007). In recent years, however, the business environment both in Japan and globally has changed significantly and the necessity for a new set of skills has been called for from a number of fields.

In response to the needs of the industrial community for human resources, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) launched a study in 2005 on Fundamental Competencies for Working Persons (shakaijin-kisoryoku in Japanese). The study concluded that these competencies are defined as “the basic abilities required in working together with various people in the workplace and in local communities”; referring to abilities that utilize basic academic knowledge and professional skills (METI 2006). The study identifies three groups of competencies. The first is an action oriented ability to step forward and persevere. This includes three factors: initiative, ability to influence, and ability to carry out tasks. The second group relates to thinking ability which includes three factors: ability to detect issues, planning skills and creativity. The third group is then focused on teamwork ability and includes six factors: ability to deliver messages clearly, ability to listen closely and carefully, flexibility, ability to grasp situations, ability to apply rules and regulations, and ability to control stress (METI website). METI has since been promoting the concept of ‘fundamental competencies for working persons’ and uses it in advocating the development of global human resources in more recent years (see, for example, METI 2010).

From the viewpoint of the industry community, Keidanren, Japan’s most influential business federation, produced a report in 2011 in which they recommend that the industry, universities and the government should cooperate in developing the human resources required in a globalized business environment. Those “global human resources” should (1) be equipped with basic skills required of business people, including abilities to initiate, communicate, accomplish, harmonize and solve problems, (2) get out of stereotyped thinking and always challenge difficult tasks, (3) have communication skills in a foreign language for mutual understanding with colleagues, client and business partners who have varied cultural and social backgrounds, and (4) have knowledge, interest and sensitivity towards other cultures and values, so as to overcome hurdles and to respond flexibly in the increasingly diverse business scene (Keidanren 2011). Their updated report proposed a range of concrete measures for global human resource development, such as strengthening English and international understanding in basic education, increasing the adoption of the International Baccalaureate, improving quality assurance of high school education, strengthening liberal arts education, and accelerating the internationalization of universities, among others (Keidanren 2013).

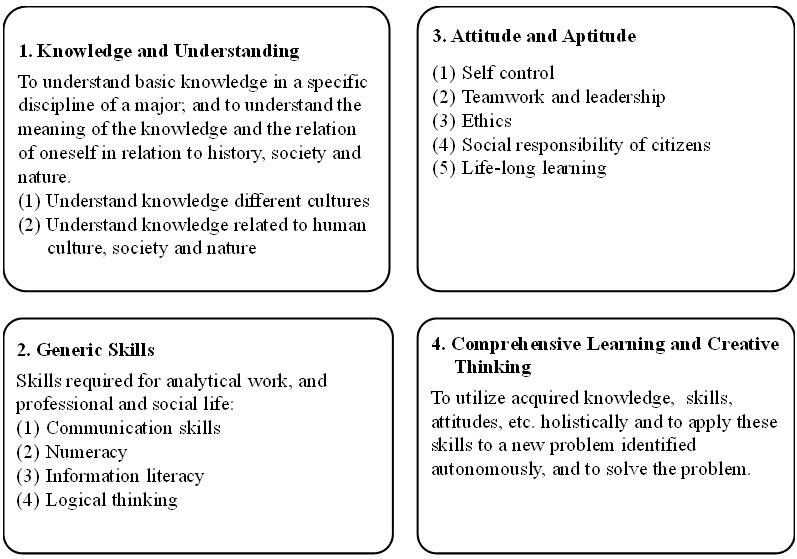

In the field of education, the Central Council for Education, an important central policy advisory body working through its university subcommittee, re-examined the meaning of learning outcomes in undergraduate students. The Council recognized the increasing demand for quality assurance of higher education in today’s globalized knowledge society and intended to provide inputs into the work of the OECD for measuring internationally comparable learning outcomes. After a year-long deliberation, the Council submitted its report to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) in 2008 noting that employers require university graduates who are effective upon entering employment at mid-career level whereas in reality, many firms look for broader general and basic skills. The report also states that undergraduate education includes objectives that go beyond merely raising industrial human resources but also to support free and democratic society, life-long learners and researchers who lead the intellectual world. Their discussions have culminated in the formulation of a concept called Gakushi-Ryoku, or bachelor’s abilities, which refer to “learning outcomes that undergraduate degree programs commonly pursue across different fields of study” (MEXT 2008:14). This concept encompasses four areas: knowledge and understanding, generic skills, attitude and aptitude, comprehensive learning experience and creative thinking (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bachelor’s Abilities

2.2 National-level policies on transferable skills

Transferable skills have thus become a key concept that emphasizes skills required in today’s work place and appear to have taken the central place in Japan in the process of formulating national policies, notably the latestNational Science and Technology Basic Plan. This five-year basic plan, which covers the period from 2011 to 2015 and was adopted by the cabinet in August 2011, incorporated the immediate needs after the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011.

The Plan also establishes four pillars as core areas of action. First, it intends to realize “sustainable growth and societal development for the future” where Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) will be strategically promoted aiming at reconstruction and revival from natural disasters. Second, it responds to “priority issues for Japan”. These include a safe and high-quality life, industry competitiveness, the resolution of global problems, promoting fundamental R&D, and common bases for science and technology. Third, it enhances “basic research and human resource development”. Fourth, it develops and implements “policy created together with society” (Government of Japan 2011).

Here, the expression used in relation to transferable skills is “to develop human resources that can be actively involved in a variety of places” as one of primary areas for the third pillar stated above. This is further elaborated as the following three concrete measures:

- Drastic enhancement of graduate school education,

- Support for doctoral course students, and diversification of career paths, and

- Development and vocational training of engineers.

In particular, the government requests universities to equip doctoral students with key management skills required by the industry as well as strengthen basic skills that cut across various specialized fields. At the same time, the industry is expected to assess competencies of graduates enrolled in doctoral courses and post-doctoral personnel, and promote their employment in non-research jobs (GoJ2011, 32-34).

At the human resources committee of the Science and Technology Council which provided recommendations leading to this plan, a long series of discussion took place. The committee deliberated on how to raise creative human resources that can continually produce innovation and play active roles in multiple fields, so as to generate a favorable circulation across sectors. They were also concerned about declining enrolment in science and engineering majors among youth and the lack of basic skills among professionals.

Within this framework set out by the Basic Plan, the White Paper on Science and Technology of 2012 discusses skills that are required of human resources who promote STI: these include problem-solving orientation that stretches widely going beyond one’s area of expertise; understanding elements of problem-solving; ability to identify hidden problems and take initiative to tackle them; and the ability to work with people in different fields with the purpose of finding solutions. These boil down to the need for developing “generic skills” that can be applied to various fields of social activities, not merely specific technical skills required for research and development (MEXT 2013, 137-138).

This White Paper also cites another related paradigm based on “design thinking” (Kurokawa 2012). It combines three elements of human-centered values, science and technology, and business in outlining the process[1] for problem-solving. It then introduces “transferable skills” within the context of acquiring generic skills for problem-solving. In the case of doctoral students for instance, the paper argues that transferable skills include not only skills to adapt to new styles of research such as a project-type research or inter-disciplinary research, but also skills that will enable active participation outside of academia, which are important for assuring a range of vocational choices. These skills can be acquired either through training or work experiences. The paper gives further reference to the Vitae Researcher Development Framework[2] that articulates the knowledge, behaviors and attributes of successful researchers.

Overall, the paper’s key message is to have open and free perspectives without being bound by specific specialized fields or sectors, and construct creative measures to apply strategic thinking toward solving social issues, and thus stimulating social change.

3 Implementation of transferable skills development

As described in the above section, the Japanese government clearly attaches importance to developing human resources that can work in different social, economic and global environments.The policy highlights universities and industries as the main players, and various policy initiatives have been put into implementation. At the same time, other players such as private sector partners and non-university education institutions are also striving to develop transferable skills. In this section, three examples of practicing transferable skills are shown: a policy program by MEXT, a private sector initiative, and a practical case study from a specialized high school.

3.1 Program for leading graduate schools

This program was launched by MEXT in 2011 with a view to mentor and guide outstanding students in doctoral programs to become international leaders with a bird’s-eye view and the creativity required to work globally in a wide range of industrial, academic, and government sectors. It is intended to support the drastic reform of graduate school education by promoting the efforts of graduate schools to create and develop world-class degree programs of assured quality, which provide a range of courses that transcend different academic fields.

In the initial year of the program, applications were sought for three types of programs lasting up to 7 years: holistic programs (to produce leaders with a wide range of expertise), multidisciplinary programs (to produce leaders with expertise in across different fields), and specialized programs (to produce leaders with a clearly defined specialization in a unique field). For this, more than 100 applications were submitted from national, public, and private universities, with 21 programs selected from 13 universities, each receiving 300 million yen for the all-round program, 250 million yen for the multidisciplinary program, and 150 million yen for the only-one program, at maximum per year. MEXT allocates 3.9 billion yen for the fiscal/academic 2011, 11.6 billion yen for FY/AY 2012, and 17.8 billion yen for FY/AY2013, and the amount of the subsequent years to be announced (JSPS website).

Example of selected leading graduate schools programs

Graduate School of Advanced Leadership Studies, Kyoto University (Holistic)

This 5-year residential program accepts 20 students annually from medicine, information, environment, economics, law and other fields in the natural and social sciences. In total 80 faculty staff are involved, including mentors and supervisors recruited from industrial, business and official circles. The curriculum is tailor-made to meet the needs of individual students. To nurture comprehensive perspectives and problem-solving ability, the 4th and 5th year students go through internship programs arranged in partnership with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the OECD and other international organizations, as well as project-based learning at firms and government offices[3].

Doctoral Program for Multicultural Innovation, Osaka University (Multidisciplinary)

In increasingly changing and diverse multicultural societies, this 5-year program seeks to aid the creation of creative and constructive models for better cohesion and understanding among people with diverse social and cultural backgrounds. Graduates will develop multicultural competencies in areas of global literacy, multilingual literacy, policy literacy, research literacy, fieldwork literacy and communication literacy through academic research and practical work within their own specialization. These graduates are then expected to become global leaders of social innovation in international organizations, global corporations, government, local authorities, universities, research institutes, and NGOs[4].

3.2 Progress Report On Generic Skills (PROG)

These generic skills are key for people to work in today’s globalized knowledge-based society. The Progress Report On Generic Skills (PROG) is a system for assessing the generic skills of university students (mostly at undergraduate level), jointly developed by Kawaijuku, one of most established private juku (cram school) companies in Japan and RIASEC, a private company that specializes in developing career education programs. PROG measures generic skills largely by dividing them into literacy – ability to apply acquired knowledge and solve problems – and competency – behavioral characteristics acquired by accumulating experiences. Literacy is explained by a six-step process comprising: (i) ability to collect information, (ii) ability to analyze information, (iii) ability to identify problems, (iv) ability to conceive solutions, (v) ability to convey messages, and (vi) ability to implement, obtained from relevant sources of OECD and various Ministries including METI and MEXT. The result of analyzing approximately one thousand classified ads has identified generic competencies that Japanese companies emphasize in the recruitment. These are grouped into issues-related competencies, interpersonal competencies and self-related competencies (Kawaijuku 2011). The number of national, public, and private universities using PROG test continues to increase every year.

Example of universities using PROG

The Case of Ehime University

Ehime University states in its university charter that it will “strive to cultivate the creativity, character, and social nature of its students and to provide them with the practical knowledge, international communication skills and analytical skills needed for individuals to live as independent members of society.” To achieve this goal, the university has introduced quasi-curriculum subjects. These include the leadership development program and an environment-focused internship program for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) among others. Some of these programs became part of official credits after substantial positive effects were reported. The PROG test was used on a trial basis with students at all undergraduate levels, and test results were analyzed along with students’ academic achievement, extracurricular activities, job placement and life style, to identify a more effective approach for developing generic skills (Kawaijuku 2011).

The Case of Faculty of Law, Kyushu International University

The diploma policy of the Faculty of Law requires students to have the ability to think critically in analyzing laws, problem-solving attitude for working as a team, aspiration for life-long learning, intention to utilize acquired knowledge for contributing to local society. These largely correspond to the concept of generic skills. The PROG test has been used over some years to complement an external formative assessment system on student performance. Results showed that the PROG literacy was correlated with students’ academic achievement at high school. It may suggest that currently university education is not equipping students with “literacy” for problem solving. This prompted the faculty to revisit its curriculum, syllabi, and lesson evaluation to gradually develop student literacy. The six-point literacy cycle was incorporated in designing a new course that uses group work and writing for problem-solving. In addition, various training programs have been introduced to nurture three-pronged competencies, including outdoor adventure education and off-campus training (Yamamoto 2013).

3.3 The practice of Hiroshima Prefectural – Hiroshima Technical High School

In this high school founded more than a century ago, sincerity, perseverance, creation and truth are all part of the school motto. The following findings are based on an interview the author had with the vice principal on October 18, 2013:

The school has been enjoying 100% placement of students who wish to be employed upon graduation. The curriculum is designed so that graduates can qualify for the national qualification certificate, in consultation with Ministry of Trade and Industry. The curriculum is periodically revised in response to changing industrial needs, and based on the views of graduates who currently hold key posts in the industry, it sometimes adds additional credits while satisfying government curriculum guidelines. The school invites special visiting lecturers from industry sectors who combine teaching and practical work in a typical one-day program. The industry requires students with nationally accredited qualification such as lathing proficiency, machining, electrical work, etc., but increasingly requiring basic abilities such as normative consciousness, devotion, and teamwork. To meet such needs, students form a team of 5 to 10 members and plan, cooperate, communicate, and produce certain products, make a presentation, answer questions, and thus develop thinking, judging, and presentation skills. The school takes academic, practical and transferable skills into consideration along with other factors. They also consult students and parents, and carefully recommend students to relevant job posting in private firms.

4 Key findings

The present review has revealed the following findings:

- The concept of ‘transferable skills’ is relatively new in Japan, and is mainly used within the academic community.

- The concept is instrumental in orienting university reform in efforts toward meeting challenges posed by globalization, responding to changing social and business culture, and enhancing student employability, often beyond their area of specialization.

- The concept of transferable skills is usually used in combination with other measures to meet the multi-faceted challenges faced by society, industry and academia.

- At present, expectations seem to be mounting among concerned parties with regards to the need to construct an agreed concept and a systematic approach to strengthening transferable skills with this work still underway.

- Noteworthy experiments have already been made, at least among universities, supported by policy initiatives and by the private sector.

- At high school level, established high schools with a long history of building trust with industry and successful graduates are enjoying an advantageous position, and are more effectively incorporating the development of transferable skills in school activities.

5 Implications for policies and practices

The emphasis on transferable skills provides an opportunity to conceive a package of skills that have at times been considered essential for an organization and wider society, be it within a research community or a private firm, to perform effectively in producing outstanding results. Some of the aspects of transferable skills have indeed been found among the inherent characteristics of leading Japanese firms. However, as job security and the tradition of life-time employment are rapidly changing, the concept of problem-solving and teamwork need to be redefined. Furthermore, as globalization puts us under a constant pressure to keep adjusting to the changing roles of experts and workers, a more systematic approach has now become crucial. Indeed, this is affecting education practices at universities and high schools as well as their relationships with industry sectors.

At present, the notion of transferable skills is mainly used in reforming the university sector – this seems reasonable, given that a dominant and increasing proportion of the majority of the Japanese labor force today have at least a first university degree. Considering the nature of transferable skills, however, the period of university life appears to be too short. In response to a burning call from industry sectors, the national policy on science and technology development reflects the concept of transferable skills, after examining similar concepts that have been discussed in various fields. A clear and commonly held understanding of what constitutes transferable skills still needs to be reached and the roles that different stakeholders should play, at least between education institutions, the industry and the government has to be clarified. At the same time, a long-lasting collaboration between academic, industrial, governmental and societal parties will also need to be institutionalized. With this in mind, we also need to position transferable skills vis-à-vis the conventional basic and advanced knowledge and skills.

References

Government of Japan (2011). “The 4th Science and Technology Basic Plan of Japan” Online:http://www.mext.go.jp/component/english/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2012/02/22/1316511_01.pdf (retrieved 22.10.2013).

Kawaijuku (2011). “Generic Skills Required by University Education Now” (in Japanese: Ima, Daigaku-Kyoiku ni Motomerareru Generic Skills) Kawaijuku Guideline 2011 No.11:53-61 (in Japanese).

Keidanren (2011). A Proposal toward the Development of Global Human Resources. (in Japanese: Global Jinzai no Ikusei ni Muketa Teigen) Online: http://www.keidanren.or.jp/japanese/policy/2011/062/honbun.pdf (retrieved 15.2.2014).

Keidanren (2013). For Developing Human Resources Who Work Successfully in the Global Stage. (in Japanese: Sekai wo Butai ni Katuyaku Dekiru Hitozukuri no Tameni) Online: https://www.keidanren.or.jp/policy/2013/059_honbun.pdf (retrieved 15.2.2014).

Kurokawa, T. (2012). “Design Thinking Education at Universities and Graduate Schools (in Japanese: Daigaku/Daigakuin niokeru Dezain Shikou Kyouiku)” Kagaku-Gijutsu Doko 2012, No.9-10:10-22. (in Japanese) Online:http://www.nistep.go.jp/wp/wp-content/uploads/0b082f6d4e4713bc307dfe37c73d5121.pdf (retrieved 22.10.2013).

Masuda, T. (2007). Considering the Source of Competitiveness of Japan’s Monozukuri. Management Sensor (in Japanese: Keiei Sensaa, Toray Corporate Business Research, Inc.) 2007/5, 22-35.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (2008). Toward the Construction of Education for Undergraduate Course: a report of University Subcommittee, the Central Council for Education. (in Japanese: Gakushi-Katei Kyoiku no Kochiku ni Mukete).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (2013). White Paper on Science and Technology 2013.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (2010). Develop Global Human Resources through Industry-Academia-Government Collaborations. A summary report of the Global Human Resources Committee of the Industry-Academia Partnership for Human Resources Development. Online: http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/data/pdf/Human_Resource.pdf (retrieved 02.06.2014).

Ministry of Trade and Industry (2006). A Draft Report by the Study Group on Fundamental Competencies for Working Persons. (in Japanese: Shakaijin Kisoryoku ni Kansuru Kenkyu-kai Chukan Torimatome) Online: http://www.meti.go.jp/policy/kisoryoku/chukanhon.pdf (retrieved 11.02.2014).

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. & Umemoto, K. (1996). A theory of organizational knowledge creation. International Journal of Technical Management, Special Issue on Unlearning and Learning for Technological Innovation. 11/7&8, 833-845.

UNESCO (2012). EFA Global Monitoring Report 2012: Youth and Skills – Putting education to work. Paris: UNESCO.

World Bank (2012). World Development Report 2012: Jobs. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yamamoto, K. (2013). Assessment and Development of Generic Skills at Faculty of Law, Kyushu International University. A presentation at PROG Seminar 2013 in Fukuoka.

Websites

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

http://www.jsps.go.jp/j-hakasekatei/gaiyou.html

Ministry of Trade and Industry

http://www.meti.go.jp/policy/kisoryoku/Fundamental%20Competencies%20for%20Working%20Persons.ppt (retrieved 02.06.2014).

[1] It goes through steps of (i) understand, (ii) observe, (iii) define point of view, (iv) ideate, (v) prototype, and (vi) test, moving back and forth as necessary.

[2] See http://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers/437091/What-is-the-Researcher-Development-Framework.html for details.

[3] Yomiuri Online: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/adv/hakasekatei2012/ and Kyoto University website: http://www.sals.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/index.html

[4] Osaka University website: http://www.respect.osaka-u.ac.jp/en/

Citation

Yoshida, K. (2014). Transferable skills in Japan: recent cases of policies and practices. In: TVET@Asia, issue 3, 1-12. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue3/yoshida_tvet3.pdf (retrieved 30.06.2014).