Abstract

Institutional networking and internationalization has been included as one of the institutional Key Performance Indicators (KPI) in most universities´ blueprints in Malaysia. The “eighth shift”, which is one particular strategy of the Malaysia Education Blueprint (Ministry of Higher Education 2013), specifically demands that internationalization initiatives are to intensify networking and collaboration with international institutions of higher education. For that reason, a networking and internationalization agenda is critically important for Malaysian Technical Universities. This paper discusses the role of networking and internationalization of universities for developing the academic staffs’ competency, focusing on staff mobility, regional collaboration as in the Regional Association for Vocational Teacher Education in Asia (RAVTE) and competencies through professional accreditation. Initially the paper explores the roles of networking and internationalization in the context of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and how it has been introduced and practiced in higher education, and then, we discuss how universities’ networking and internationalization contribute to staff mobility, research, and technical skills development.

1 Malaysian Technical Universities Network (MTUN)

In the present era of globalization, technology is another choice for the students to choose besides engineering, pure sciences and social sciences. There are four Technical Universities in Malaysia offering technology programs. The Universities are: Universiti Malaysia Pahang (UMP), Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UNiMAP), Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka (UTeM) and Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysian (UTHM). Among the four universities from the Malaysian Technical University Network, UTHM has been actively involved in supporting the Ministry of Education to train technical and vocational education teachers under the Faculty of Technical and Vocational Education (FTVE). UTHM struggles in the global circle of tough competition in order to maintain capacity and pursue the highest university ranking. Most universities have established systems to ensure academic staff competency, in order to improve the capacity of their workforce. For that reason, institutional networking and internationalization has been included as one of the institutional Key Performance Indicators (KPI), in most universities´ blueprint for higher education in Malaysia (Ministry of Higher Education 2013), and being reflected in the universities´ mission and vision.

“Global Prominence in higher education requires four elements – visibility, recognition, distinction and expansion. To tap these elements, the Ministry will strengthen the promotion, marketing and value proposition of Malaysia’s higher education system; identify ways to increase the enrolment of high calibre international students; and establish stronger ties with the global higher education community.” (Ministry of Higher Education 2015).

In its Malaysia Education Blueprint, the Ministry of Education identified 10 shifts that would be needed to take the Malaysian higher education system to the next level. The “eighth shift” includes the recommendation to intensify networking and collaboration with international higher education institutions worldwide. The networking and internationalization agenda is critically important for Malaysian Technical Universities (MTUN), especially UTHM. Maintaining networking and internationalization is not merely for getting international funds, in order to enable institutional staff to intensify research and publications, or pursuing the best university ranking. It is beyond the students’ mobility and also involves a wider scope and capacity including transfer of knowledge, technology, academic research, and educational resources (UNESCO 2009). An exemplary benchmark of win-win networking and internationalization initiated by UNESCO, was discussed in an International Meeting on Innovation and Excellence in TVET Teacher/Trainer Education in 2004. This is a good benchmark for research and development in the networking and internationalization context. Another specific example that is closer to sharing educational resources was the initiative of the European Union Erasmus program, hosting staff mobility that involved 33 participating countries (British Council 2014).

Although networking and internationalization is good for the university as an education institution in terms of capacity, sharing of educational resources would be beneficial for institutional staff competency. A program such as staff mobility actually fulfils almost all of the key elements of the networking and internationalization objectives. It is during the mobility period, that staff have great opportunities to increase competency and learning through experience. This competency enhancement would improve several areas of skills depending on the focus and objectives of the mobility program (Buenning & Zhao 2006). A mobility program that is focusing more on research and development would increase staff competency on research skills, which has a positive impact on teaching as well.

2 Relationship between internationalization of TVET institutions with their competence development

ASEAN and the East-Asian Summit (EAS) organize internationalisation activities of TVET institutions under an agreement of partnerships among the involved nations. One of the agendas under ASEAN member states (AMS) and EAS has inspired the flexibility of goods, students and workers across the ASEAN regions starting in 2015. This means that the flexibility among TVET staff to be mobile within these countries will also be greater. In TVET institutions, the international flow of staff requires more attention on enhancing the effectiveness of qualifications and skills recognition across regions. Common understanding between the regions needs to be addressed, and this is through the newly developed East Asia Summit Regional TVET Quality Assurance and Qualification Frameworks, and the Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA).

The function of this framework is basically to provide a standard alignment in the requirement of what the mobile staff should be able to do in trade services among the regions involved, and standard qualifications that should be addressed as requirements fulfilled by the staff. MRA then will enable the qualifications of professional services suppliers to be mutually recognized by all of these regions; which literally means that staff could use the qualifications to practice their expertise in any of the countries. Despite the advantages however, the development of such framework needs to be rigorously planned, researched and reviewed if the framework is to be implemented. It is the role of AMS and EAS regions to carefully design the development to optimize the advantages that the framework could provide. Two professional bodies – the Professional Regulatory Authority and the Department of Labor and Employment are currently in the process of putting policy measures in place to facilitate MRA implementation in Malaysia. Although still under progress, with this standard framework, regions within the EAS are connected because every qualification that the staff receives will be similarly recognized among the regions. This recognition will not only promote human resource development, but also provides a means for bridging any development gaps, assisting economic development, promoting friendship and mutual understanding among the people in the EAS regions, and of course enhancing regional competitiveness. How does this implementation increase competencies of the staff?

In the context of regional competitiveness, within the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the issue of gaining standard recognition and qualifications for staff whose mobility has gained increased prominence in recent years is critical. Added impetus is coming from the plan to move to a common labour market by 2015. “Sending countries” such as Laos and Cambodia are keen to develop their TVET systems and skills recognition arrangements quickly while “receiving” countries such as Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei at the moment already have a range of skills training and recognition systems in place for their own workers. These systems will persist and it remains to be seen how ASEAN workers from elsewhere will be accredited by these receiving countries in the future. Both sending and receiving countries in ASEAN have different motivations but towards a similar goal – to improve skills development and accreditation mechanisms. The sender countries would like to provide more skilled workers who could be employed abroad at appropriate employment levels and wages, as well engaging with international economic development. On the other hand, receiving countries are seeking a greater guarantee of the availability of well-trained workers. Both sending and receiving countries however, apparently will strive to increase the competencies of their workers, since if standard recognitions are to be developed, they must be within the viability of a true common labour market. All of these will depend on how these skills recognition arrangements will emerge and develop.

3 Mobility and flexibility of staffs’ development in TVET

Globalization increases international competitiveness in TVET. The gap in knowledge and ownership of advanced technologies between developing and developed countries has always been large, with developing countries often adopting technologies and solutions innovated elsewhere but lacking the capacity and resources to adapt most of the technologies to the local context. Transfer of technical knowledge through TVET combined with creative skills and career guidance, can raise the innovative capacity of developing countries, allowing them to produce quality technological solutions for their own context and export and to keep up with the developing world. The observed global trend is increasing career mobility and, as such, TVET is no longer merely expected to provide learning opportunities for skills development, but also to enable employees to prove themselves to be flexible in new working environments as a result of their broad individual competence profile. TVET is in a position to enhance human resource development within the context of this shift from a one-job-for-life culture to higher career mobility through focusing on competence development as opposed to just knowledge acquisition.

Competency is identified through knowledge, skills, attitude and other individual characteristics (Srinivasa Rao & Prabitha 2012) and focuses on what is expected of an employee in the workplace, not only technical but also social, rather than just on the knowledge acquisition. In these definitions, TVET – sometimes also known as Vocational Education and Training (VET) or Career and Technical Education (CTE) can be regarded as a means of preparing for occupational fields and effective participation in the world of work (Cinter 2001). It also implies lifelong learning and preparation for responsible citizenship. In its broadest definition, TVET includes technical education, vocational education, vocational training, on-the-job training, or apprenticeship training, delivered in a formal and non-formal learning environment. Table 1 summarizes the TVET-modes of delivery.

- Technical education mainly refers to theoretical vocational preparation of students for jobs involving applied science and modern technology. It emphasizes the understanding of basic principles of science and mathematics and their practical applications, rather than the actual attainment of proficiency in manual skills as it is the case with vocational education. The goal of technical education is to prepare graduates for occupations that are classified above the skilled crafts but below the scientific or engineering professions.

- Vocational education and training prepares learners for jobs that are based in manual or practical activities, traditionally non-theoretical and totally related to a specific trade, occupation or vocation, hence the term, in which the learner participates.

Table 1: Modes of TVET delivery (World Bank 2014)

| Technical | Vocational | |

| Formal | Technical education institutional-based |

Vocational education, Vocational training work-based training |

| Non-formal | Work-based training Non-institutions TE providers |

On-the job training Non-institutions VE providers |

Professional development of staff means to upgrade all those skills required to execute a task of TVET staff in transferring knowledge, expanding networking and improving their competency in a particular area. It means that staff maintains, improves and broadens their knowledge and skills to develop their required competencies (Powar 2004). The mobility of the internalization process provides different scenarios based on sharing knowledge and experience. TVET is in the position to contribute to global development, participation and cooperation. TVET systems allow a broad participation of people, who can develop relevant competences, if it is adapting to the changing needs of the local, national and global labor market and economic sectors.

Flexibility in training delivery and strengthening qualifications through international recognition need to be planned to ensure academic staff are competent up to international standard. This includes, for example, creating a framework for recognizing prior learning, establishing clear pathways for re-entry into the education system, developing a national credit system to enable accumulation of modular credits over time, and stipulating clear criteria for recognizing prior experience.

4 Competency based skills needed

The education sector’s success in addressing the challenges of globalization will help a country to produce internationally competitive and competent human resources. According to Sharma (2008) human resources are the assets of a country required to achieve national competitiveness. Human resource development (HRD) plays an important role in achieving sustainable development. It is a process of increasing the knowledge, skills and competences of the people in a society. Competencies are identified through knowledge, skill, attitude and other individual characteristics (Srinivasa & Pratibha 2012). Competencies acquired show an individual’s strengths so that the organization will know their value and capability in their job performance. To develop competencies, the mapping of an organization’s goals and workers skills should be identified. According to (Srinivasa & Prabitha 2012) competency mapping in organizations should have specific support and assessment; provide methods to enhance workers competences and demonstrate what type of skills and knowledge are required to improve competencies. Competency programs should be developed to increase the quality of human capital in TVET. The characteristics of competency programs are the following: competency are carefully selected; integrate theory and skills; detail training material; methods of instruction and learning should be self-paced and flexible training (Anane 2013).

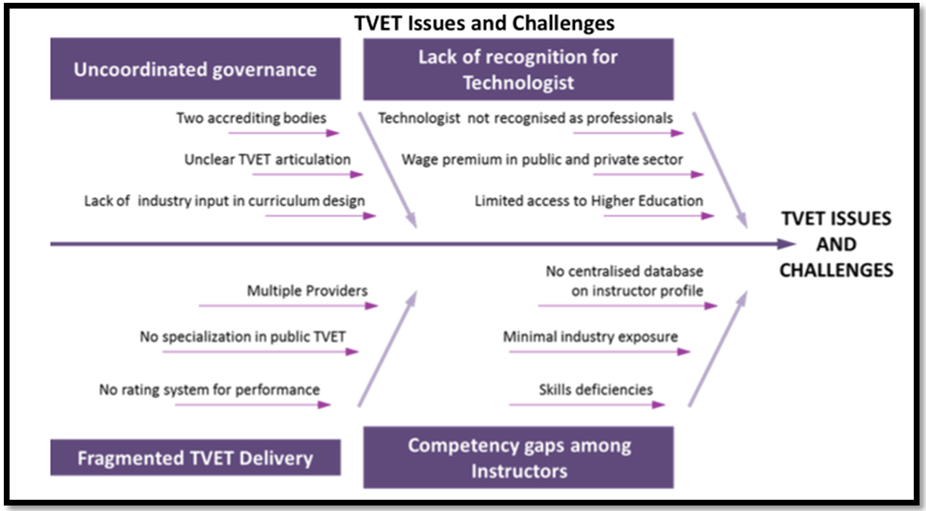

Issues and challenges in the Tenth Malaysia Plan, 2011-2015 focused on uncoordinated governance of TVET and fragmentation resulting from technology competency gaps among instructors. Mainstreaming and broadening access to quality TVET addressed industry needs for skilled workers. These efforts increased the number of school leavers pursuing TVET from 25% in 2010 to 36% in 2013 (Economic Planning Unit 2015). Even though TVET mainstream is moving towards a successful field, issues and challenges in competency gaps among instructors persist. Fig. 1 shows issues and challenges faced in TVET sectors in Malaysia. These highlighted issues will be seriously focused in the Eleventh Malaysia Plan, 2016-2020).

Figure 1: Malaysia TVET issues and challenges

The Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 will focus on several initiatives to harmonize delivery of TVET towards economic development and demand driven by industry to ensure a quality skilled workforce. Competencies are needed in TVET graduates to increase the employability rate within 6 months after graduation. The Economic Transformation Programme (ETP), suggests Malaysia will require an increase of 625,000 TVET enrolments by the year 2025. However, there is an undersupply of TVET workers in some key areas. Further, TVET is seen as a less attractive pathway than university education, thereby limiting the number of students, particularly high-performing ones, who apply for such courses. Malaysia needs to move from a higher education system with a primary focus on university education as the sole pathway to success, to one where academic and TVET pathways are equally valued. To achieve these outcomes, UTHM must intensify industry involvement and partnerships, streamline qualifications, improve coordination across the regional countries and their Ministries and, with other TVET providers, enhance TVET enrolments. Key initiatives include:

- Collaboration with industry to support industry-matching curriculum design and proposed new delivery models through partnership.

- Improvement in coordination across the countries and Ministries of various TVET providers to eliminate duplication of programmes and resources, enable greater specialization in areas of expertise, and improve cost efficiency; and

- Coordination with other countries and ministries supported by various agencies, in offering TVET programmes to streamline the international qualification framework and ensure alignment with major industry associations, and pursue international accreditations for TVET programmes.

5 Conclusion

The impact of networking and internationalization can only be seen positively, especially with regard to the standards and quality of programs offered, if all partners in the Asian countries show their commitment and are proactive. Proposals and commitment should be accepted with understanding and be accepted by all parties. These opportunities can be achieved and implemented in 2015, when Malaysia will lead the Asian community. A new work environment, new resources, a new social environment, new ideas, and new research fellows and colleagues would provide different context in doing this research. On the other hand, the mobility program that is focusing on skills training for a particular timeframe, staff mobility, staff and student exchange, consultancy through MoU and MoA signing and further collaboration could enhance their technical skills and learning new technologies used by the hosting country. UTHM can be seen potentially to lead several activities and projects to ensure close collaboration among local and international parties from various countries to obtain an advantage.

References

Anane, C. A., (2013). Competency Based Training: Quality Delivery for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Institutions. In: Educational Research International. Vol. 2, No. 2, 117-127.

British Council (2014). Erasmus+ Staff mobility. Online: http://www.britishcouncil.org/study-work-create/opportunity/work-volunteer/erasmus-staffmobility (retrieved 14.07.2014).

Buenning, F. & Zhao, Z. (2006). TVET Teacher Education on the Threshold of Internationalisation. Germany: Internationale Weiterbildung und Entwicklung GmbH.

Cinter (2001). Modernization in Vocational Eduation and Training in the Latin American and the Caribbean Region. Montevideo.

Economic Planning Unit (2015).Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training to Meet Industry Demand. Online: http://www.epu.gov.my (retrieved 13.06.2015).

Ministry of Higher Education (2013). Pelan Strategik PengajianTinggi Negara. Online: http://www.moe.gov.my/userfiles/file/PPP/Preliminary-Blueprint-Eng.pdf (retrieved 14.07.2014).

Powar, K. B. (2004). Internalization of Higher Education: An Aspects of India’s Foreign Relations. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House.

Sharma, K. D. (2008). Regional Accreditation: Mechanism for Cross-Border Mobility for TVET Graduates. Online: http://202.4.7.101/files/2008.05.30.cpp.dhameja.regional.accreditation.cross_border.mobility.tvet.paper.pdf (retrieved 14.07.2014).

Srinivasa Rao, K. & Prabitha, S. (2012). Competency Based Human Resource Development Mechanism: A Case Study of NTPC.In: International Journal of Organization Behaviour & Management Perspectives, Vol. 1, No. 2, 165-169.

UNESCO (2009). Internationalization, regionalization and globalization. Online: http://www.unesco.org/en/the-2009-world-conference-on-higher-education/sub-themes/internationalization-regionalization-and-globalization/ (retrieved 14.07.2014).

World Bank (2014). TVET Issues and Debates, World Bank Institute. Online: http://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/243625/bTVET%20Issues%20and%20debates.pdf (retrieved 18.3.2015).

Citation

Hassan, R., Masek, A., & Mohamad, M. M. (2015). The role of networking and internationalization of technical universities in academic staff competence development. In: TVET@Asia, issue 5, 1-9. Online: https://www.tvet-online.asia/issue5/hassan_etal_tvet5.pdf (retrieved 23.7.2015).