Abstract

The demand for skilled workers in the Indian labor market and the current focus of the Indian government on skills development require Vocational Education and Training (VET) institutes to produce highly employable graduates. However, due to the incongruence between the central and state governments, training institutes and industry, there is little clarity on the concept and components of employability and the factors that can effectively enhance the employability of VET graduates.

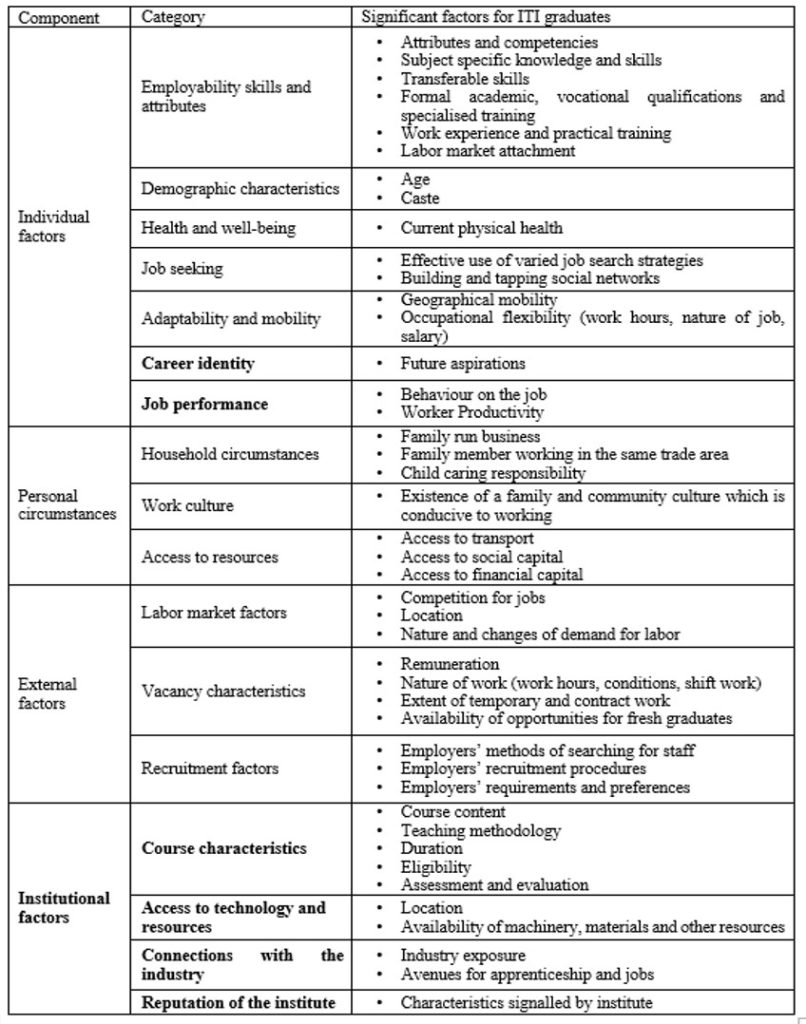

This paper aims to provide a conceptual framework to understand and analyze the employability of Indian VET graduates. The most prominent group of VET institutes in India, the government Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), was chosen for this study. Using qualitative research tools, data was collected from ninety-seven stakeholders, comprising twenty-two ITI graduates, forty-two employers and consultants, twenty-nine staff members from government ITIs and four private ITI graduates from the city and suburban areas of Mumbai. The empirical data was analyzed using McQuaid and Lindsay’s (2005) framework for employability and an extended form of this framework suited to Indian VET graduates was developed. The framework consists of four components – individual factors, personal circumstances, external factors, and institutional factors, each of which is further broken down into categories. This framework will provide a unifying structure to direct and organize the different agents in the Indian VET system. Consequently, it will help to enhance the employability of graduates in a holistic manner.

Keywords: Vocation Education and Training (VET), skill development, Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), employability, conceptual framework

1 Introduction

India is a developing country with a rich demographic dividend. Skill development through vocational education and training (VET) is necessary to utilize this demographic dividend effectively for the economic growth of the nation (Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship 2015, 2). Vocational education and training is defined as a form of education and training that “prepares an individual for a particular profession, trade or employment” (Tammaro 2005, 77). VET programs play two crucial roles in India – providing training to youth leaving school and supplying skilled manpower for sustainable development (Wahba 2012, 1). Furthermore, organizations like the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Bank recommend VET programs for the reduction of poverty and the promotion of economic growth in developing nations like India (Comyn & Barnaart 2010, 49).

Indian VET institutes are increasingly required to provide skilled manpower for the growing needs of the nation. However, the employability of graduates has been persistently low despite several initiatives and reforms (Neroorkar & Gopinath 2019, 7). One of the prime reasons for this is that the responsibility of the Indian VET system is distributed between the central government, state governments, and private entrepreneurs and there is a severe lack of coordination between these entities (Rajput 2009, 60). The issue is further complicated by the mismatch between the training institutes on the one hand and industry on the other. Research in the area of employability has failed to provide valuable guidance for the Indian VET system since it is largely focused on graduates who have pursued higher education courses like engineering and MBA programs, whilst VET programs have been seriously neglected. Additionally, empirical studies on employability tend to examine employability skills like problem solving, innovative skills, and task orientation narrowly rather than the components of employability such as individual factors, personal circumstances, institutional factors, etc.

The present paper aims to strengthen the understanding of the employability of Indian VET graduates by providing a framework to conceptualize their employability. A conceptual framework provides a structure to analyze issues and allows for solutions (Rojewski 2009, 20). This framework will bring coherence to current practices in the Indian VET system.

2 Research Setting – Industrial Training Institutes

The ITIs are the most prominent group of VET institutes in India. The government of India started the ITIs in 1950 to accelerate the process of industrialization in the country (International Labour Organization 2003, XII). With time, many private ITIs were also established. At present there are 11,964 ITIs in India (Directorate General of Training 2019). Eleven such government ITIs are located in the city and suburban areas of Mumbai. Different training schemes are prevalent at these ITIs. The craftsman training scheme (CTS), being the most popular and largest of all the schemes (Prakash & Gupta 2002, 1267), was chosen for this study. Trades like fitter, welder, wireman, painter, computer operator and programming assistant, cosmetology, fashion design, etc. are offered under the CTS to students aged 14 years and above. The minimum qualification depends on the trade and is generally 8th class (i.e. 8 years of formal schooling) or 10th class (10 years of formal schooling). The duration of the trade certification courses is generally one or two years, after which the student may pursue apprenticeship training in the industry.

In this study, empirical evidence was gathered from graduates, staff members, and employers associated with the government Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) in the city and suburban areas of Mumbai. Data was used to adapt and extend the employability framework put forth by McQuaid and Lindsay (2005) to s cuit Indian VET graduates. This particular framework was chosen because it provides a comprehensive view of the supply and demand factors of the labor market.

3 Method

3.1 Data collection

In this paper, employability is operationalized as the ability to gain and maintain employment (Hillage & Pollard 1998, 2). Following this definition, we conceptualize an individual’s employability as two capabilities. The first individual capability is to secure employment in the form of one or more than one job. The second is the individual’s capability to sustain themselves in the job(s) without a gap of more than 4 months at a time. The 4-month period was chosen as the average duration of unemployment and the time between two jobs is approximately 3 to 3.9 months (Card, Chetty, & Weber 2007, 115). This paper presents a part of the findings of a larger mixed methods study on the employability of ITI graduates in Mumbai. The sample for this paper included ninety-seven stakeholders (n=97). For the sample of ITI staff and graduates, the government ITIs located in Mumbai were visited. Interactions with staff members were held at the institutes themselves. Students’ contacts were secured from the institutes and they were interviewed over the phone. For the employer sample, convenience sampling was used. The tools used for the qualitative data collection were interviews, focus group discussions, questionnaires, and anecdotal data logs. The employer interviews were predominantly conducted in English, while the interviews with the ITI instructors, staff, and graduates were conducted in Marathi or Hindi. Table 1 provides the number of respondents in each stakeholder group and details of the data collection tools used.

Table 1: Characteristics of respondents in the study

| Type of respondent | N | Characteristics | Data collection tool used |

| ITI Instructors and Staff | 29 | Instructors (22), Office Staff (1), Foreman (2), Apprenticeship in-charge (2), Principal (1), Deputy Director of Directorate of Vocational Education and Training (1) | Interview (n=20), focus group discussions (n=4 and n=3), and anecdotal evidence (n=2) |

| ITI graduates | 22 | Mechanical draughtsman (2), Welder(4), Diesel Mechanic (1), Electronics Mechanic(1), Motor Mechanic(1), Sheet metal fitter (1), Civil draughtsman(2), Machinist (1), Basic Cosmetology(1), Dress Making (3), Secretarial Practice(1), Computer Operator and Programming Assistant (3), Information & Communication Technology System Maintenance (1) | Interview |

| Employers | 42 | Level: Mid-level (11), Senior (25), Consultants (2) and Senior (4), Type of company- Manufacturing (24), Service (10), Manufacturing and Service (4), Staff from apprenticeship training schools at government companies (4) | Interview (n=16), questionnaire (n=23), and anecdotal evidence (n=3) |

| Private ITI graduates | 4 | Fitter (2), Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Mechanic (2) | Interview |

| Total (n) | 97 |

It should be noted that the interview, focus group discussions, and questionnaires utilized the same set of questions and differed only in the mode of administration. The interview and focus group discussions were conducted verbally while the questionnaire was administered electronically. The appendix provides the list of questions. In cases where the respondents did not have time for the interview, anecdotal evidence was collected. Data for all three stakeholder groups was gathered until saturation, a process which focuses on the variation in data rather than the frequency of a particular event or phenomenon (Morse 1995, 148).

3.2 Data Analysis

In the case of interviews and focus group discussions, an audio recorder was used with the consent of the respondents. Initially, interviews and discussions were transcribed and analyzed simultaneously as qualitative data was being collected. For interviews in Marathi and Hindi languages, the authors translated the interviews into English along with the above. However, as the study progressed, it was found that for this particular type of research, which used open-ended interviews to collect general perceptions of the participants, verbatim transcription was not adding much value (Halcomb & Davidson 2006, 39). In fact, as pointed out by Fasick (1977) verbatim transcription was turning out to be very expensive in terms of time and effort (549). Therefore, an alternative method of developing codes by directly listening to audio recordings (Gravois, Rosenfield, & Greenberg, 1992; Neal et al. 2015) was applied to the interviews conducted later in the study. While researchers like Crichton and Childs (2005) and Evers (2011) have used specialized software for this kind of coding, the authors chose to do it manually.

In this process, for the first level of analysis the authors started with a sheet in Microsoft Excel for the coding. Three columns namely, open code, quote and respondent’s name were created in this sheet. Next, the authors played the interview audio clip. While listening to the audio clip, whenever a code was heard, the player would be paused and the code would be noted in the Excel sheet. The authors would then write the verbatim quote from the interview (translated into English wherever necessary) and the respondent’s name in the respective columns. These steps were applied to analyze each audio clip. Where more than one respondent’s interview yielded the same codes, the particular quote and the respondent’s names would be added in the respective columns. In this way the authors developed around 100 codes in the first level of analysis. Academic performance, student attitudes, student expectations, technical knowledge and skill were some of the codes that emerged from the raw data. This method of analysis saved a great amount of time, which was then used to gather data from more respondents and substantiate the findings. Field notes taken during these interviews were also used for the data analysis (Neal et al. 2015, 123; Tessier 2012). In the case of respondents where only anecdotal evidence was available, that was used in the analysis.

This empirical data gathered from the interviews, field notes, and anecdotal records was then analyzed using the employability framework developed by McQuaid and Lindsay (2005). The open codes developed in the first stage of analysis were merged and organized into components as per this framework. While the three components of individual factors, personal circumstances and external factors from the original framework were maintained, a fourth component of ‘Institutional factors’ was also added to the framework following the data gathered from the stakeholder groups in the study. Similarly, within the component of individual factors, two new categories, i.e., career identity and job performance, were included in the framework in light of the findings. These additions to the original framework are shown in bold text in the framework in table 2.

4 Findings

Table 2: An employability framework for Indian VET graduates (adapted from McQuaid & Lindsay 2005)

4.1 Individual factors

Employability skills and attributes: With reference to Table 2, several significant attributes affecting employability of Indian VET graduates were mentioned by respondents in this study. They were honesty, personal presentation, positive attitude, perseverance, self-discipline, subject interest, initiative, and proactivity. Competencies like versatility, multi-tasking, and innovative thinking were also noted.

“Honesty is one of the most important qualities I look for in my workers.”

Self-employed graduate, Fashion design course

“Many of my jobs are located away from Mumbai where skilled workers aren’t easily available. If I can get a worker who can do the job of a fitter, cutter and fabricator he is a great asset as he is effectually doing the work of three people. This wasn’t a requirement earlier but changes in the industry have made multi-tasking essential today.”

Employer, service company

Subject specific knowledge and skills and transferable skills like computer skills, communication, comprehension, and application were also found to significantly affect VET graduates’ employability.

“A prospective employee must possess suitable technical knowledge and skills or else he is rejected immediately by the company.”

Graduate, mechanical draughtsman course

“Students passing out of our trade need to have good communication skills as they interact with top level managers and executives within the company and with company clients.”

Instructor, secretarial practice course

Academic qualifications (generally 12th pass, i.e. having completed 12 years of formal schooling or graduated from Bachelor programs), vocational qualifications like the ITI certificate and specialized training gained during apprenticeship, at company level or through specialized courses were found to affect the employability of VET graduates. Some examples of specialized skills were Tally for IT trades, 6G welding for welders, and computer-aided design for fashion designers.

Work experience and practical training, during the VET course, apprenticeship training and through industry exposure visits, were also found to affect the employability of graduates.

“The industry is very different from our institutes. I feel thorough practical training and preparation for the industry environment are two things that can develop good workers.”

Graduate, fashion design course

The labor market attachment of graduates in terms of the time period for which they have been employed or unemployed was also found to affect employability. Career continuity with minimal breaks was found to enhance employability, while frequent job changes were said to negatively impact it.

Demographic characteristics: The effect of age on the employability of VET graduates depended on company requirements. Some employers preferred younger workers due to their lower salary expectations, others preferred older workers for their experience and perceived stability and yet others did not have age-related preferences. Age was also found to affect the progress of VET graduates as promotions in some organizations were contingent upon seniority. The group of VET graduates affected their employability primarily in case of government companies due to group-based reservations or lower eligibility criteria for other persons.

“I prefer candidates in the age group of 14 to 25 years. But if an individual shows a positive attitude and willingness to work hard, I will certainly give them an opportunity in my company irrespective of their age.”

Employer, manufacturing and service compa

Health and well-being: The health of skilled workers at the time of recruitment and on the job was found to affect their employment prospects and progress at the workplace.

“Our organization has to conform to the standards set by the International Labour Organization. Hence, it is mandatory that our employees are medically fit. They have to undergo annual medical check-ups. Their insurance is also our responsibility.”

Employer, service company

Job seeking: VET graduates’ use of varied job search channels like online portals, recruiters, newspapers, etc. was found to be directly correlated with their employability. Furthermore, the possession and effective utilization of a social network within the field was found to affect their access to opportunities and thus impact their employability.

Adaptability and mobility: Geographical mobility in terms of willingness to move within the city, travel to far-off locations and relocate, occupational flexibility in terms of salary, working hours, and nature of work were also mentioned by respondents.

“My students work in beauty parlours. Employers expect them to clean the parlour, buy materials or run errands. Some students dislike doing anything apart from beauty work. Another issue is that of unisex parlours. Many girls are not comfortable working in that environment. Individual flexibility and the extent of adjustment decide whether they will continue on the job or not. Some compromise, some don’t.”

Instructor, Cosmetology course

Career identity: The career identity of an individual is how individuals see themselves in the context of their career and consists of two questions, “who I am?” and “where do I want to be?” (Fugate, Kinicki, & Ashforth 2004, 17). VET graduates generally work, study further, or start their own enterprise. This study showed that pursuing these different career paths and the aspirations of graduates affect their employability.

“This is a small scale company and on the job training is an expense. During recruitment, I try to gauge the candidate’s seriousness about working in my company. I avoid recruiting ambitious workers who will likely take the experience for few months and then leave for a larger company.”

Employer, Manufacturing company

“I do not have an issue if a worker wishes to study further while he is employed in my organization, so long as it doesn’t affect their performance.”

Employer, Manufacturing company

Job performance: Respondents in this study mainly referred to two components of job performance – on the job behavior and worker productivity. Workers who behave in a manner favorable to the organization were said to be able to maintain employment successfully. Issues like alcoholism, theft and disrespect for authority were some of the behaviors that were said to negatively affect the process of maintenance and securing of new employment by VET graduates. Worker productivity was found to be measured using tangible products like the number of garments stitched in a given time period or typing speed in words per minute. Workers with medium to high productivity could sustain employment while those with low productivity could not.

4.2 Personal Circumstances

Household circumstances: Graduates, having a family member either working or running an enterprise in the same trade area as them, were found to have higher employability due to greater access to job opportunities. Child caring responsibilities were found to affect the employability of female ITI graduates to a large extent.

“Female students do not pursue employment once they get married and have children. Hence, a large percentage of graduates from these female dominated garment trades like dressmaking, fashion designing, and computer operator and programming assistant do not end up working after they complete their training.”

Deputy Director, DVET, Mumbai

Work culture: Students pursuing VET courses in India belong to economically and socially backward families (Tilak 2003, 680). It was pointed out by respondents in the study that these students could easily pursue unskilled work or traditional occupations unrelated to their trade, due to better access to such jobs and quick returns. The family and community culture thus emerged as an important factor in this context. A conducive culture enhanced their employability by facilitating them to take up employment and sustain in their respective vocational trades.

Access to resources: Access to resources like private and public transport and large social capital was found to enhance the employability of VET graduates. The presence of a mentor who could guide the student was found to positively affect his/her employability. Financial capital emerged as a factor affecting the choice of job as a graduate (who is financially stable) can afford to be selective about jobs, while one who is not has to opt for any job he/she gets.

“The environment in these students’ homes is not study oriented or focused in terms of work and productivity. Around 10% of the students have only one parent or guardian. In such a situation, having a mentor makes a lot of difference to them. The guidance they receive is valuable for their career.”

Foreman (supervisor), ITI Mumbai

“ITI graduates have many demands like high salary, getting a job through referral, working only in their trade area or getting a job in a big company. If I was so fussy, I would have been jobless. I am in need of money and I am ready to take up any job. I am now a cab driver and I am satisfied with my job.”

Graduate, computer and programming assistant course

4.3 External factors

Labor market factors: Competition of VET graduates (especially in the engineering and IT trades) with inexpensive non-certified labor on the one hand and more educated diploma holders and engineers on the other was found to significantly affect their employability. The location of graduates with respect to the industrial area, changes in the labor market in terms of the level of automation (e.g. making manual work redundant), and the demand for a certain skill in the Indian economy were other labor market factors said to affect their employability.

“There are several five star hotels near our institute. We often get requisitions for hospitality apprentices. However, many of the students reside in far-off parts of Mumbai and they are unable to travel all the way. They cannot take advantage of these opportunities.”

Apprenticeship in-charge, ITI Mumbai

“In the last decade or so, engineering companies have adopted the CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining process. Manual operation of a lathe or mill is fast getting outdated. Workers need to be able to use CNC to secure their jobs.”

Instructor, fitter course

Vacancy characteristics: The pay scale offered, work hours, conditions of the workplace, and the extent of shift work were the vacancy characteristics mentioned by respondents in this study. Presence of temporary and contractual work was also mentioned in this context. It was found that especially in manufacturing companies, manpower requirements vary as per the production cycle and these companies recruit contractual labor as per their need. The extent to which freshers are recruited for skilled work was noted as another factor affecting the employability of VET graduates.

“My company designs and manufactures steel products. One of my basic requirements is that workers should be willing to work in shifts – otherwise I cannot recruit them.”

Employer, manufacturing company

“The fashion industry has long working hours. Most of our students are females and once they start a family they cannot continue on the job. Self-employment, on the other hand, can be pursued as per their convenience and from their homes. So those who take up self-employment as soon as they graduate tend to sustain while those in the industry tend to leave their jobs.”

Instructor, fashion design, Women’s ITI

Recruitment factors: Different kinds of processes of searching for staff, recruitment, and varying employer preferences were mentioned by the respondents in this study. For recruitment, employers were found to approach institutes, contractors, and recruitment agencies, advertise in newspapers, online or at the company gate. With respect to preferences, some employers were particular about verifying and maintaining records of employee identity cards and educational certificates while others were not. Medical fitness was an essential requirement in some of the companies but not in others. Some companies gave weightage to the grades that the applicant had scored in the scholastic and vocational courses, others only needed the applicant to have the necessary qualification and some small-scale companies were willing to recruit students who had failed their ITI course as well. All these recruitment factors were found to affect the employability of VET graduates.

4.4 Institutional factors

VET in India is provided either by public or private institutes. The quality of training and infrastructure in private institutes is poor compared to public institutes (Tilak 2003, 682). This is primarily because a large number of these private institutes are neither recognized nor regulated by the government (Mehrotra 2014a, 269). Despite this, private institutes are growing at an alarming rate from less than 2000 in 2007 to around 8000 in 2012 (Mehrotra 2014a, 273). Due to this variation between the quality of training and infrastructure provided by the different institutes in India, the VET institute from which a student graduates is an important determinant of their employability.

McQuaid and Lindsay’s (2005) framework was extended to include this component of institutional factors as all three stakeholder groups in this study mentioned the crucial role of the institute in effecting employability. This component has been broken down into four categories, namely course characteristics, access to technology and resources, connections with the industry, and reputation of the institute.

Course characteristics: Outdated curriculum was observed to have a negative impact while upgradation of the curriculum was taken to have a positive impact on employability. The language of instruction, technical level of the syllabus, depth of the curriculum, and training of the instructors were the other factors stated in this context.

“The technology we teach is old and outdated while the outside world has moved far ahead. Old technology should be retained as it forms the basis on which we can teach new concepts. But advancement in the curriculum is very essential to develop competent workers. Training of the instructors is also essential so that they can teach the new curriculum.”

Instructor, electronics mechanic course

“Institutes that were initiated about 50 years ago are still maintaining the same procedures, equipment and budgets for consumables. Welding has undergone a lot of modernization. What was good welding equipment and procedure in those days is obsolete today. These graduates come to us with outdated ideas. They are not exposed to recent technologies. This severely lowers their chances for employment.”

Employer, service company

The effect of teaching methodology on the vocational career of VET graduates was largely mentioned by students in the sample. Students mentioned that teaching related factors like teacher professionalism, involvement of teachers, inclusive teaching strategies, and rigorous practical training had a positive impact on employability. On the other hand, poor teaching practices like lack of professionalism, lack of involvement, encouraging rote learning, and focusing solely on theoretical concepts were considered to have a negative effect on employability.

Course duration, entry-level qualification, and the nature of assessment and evaluation were also found to affect employability. Shorter courses were considered favorable for the employability of VET graduates as they allowed earlier entry into the workforce. In terms of eligibility criteria, the institute – industry match came up as an important factor. Some trades have an eligibility criterion of 10th pass (i.e. 10 years of formal schooling) but the industry needs 12th pass (i.e. 12 years of formal schooling) candidates. A 10th pass ITI holder thus has lower employability than one who has passed 12th grade. The method of assessment and evaluation was also found to affect marks scored in the certifying exam, which in turn was said to affect graduates’ employability.

“Most of these students are minimally qualified and have low comprehension levels. They find it difficult to understand complex engineering concepts. Second, they are not very comfortable with the English language. So they face difficulties in answering their papers. Add to this the issue of negative marking which lowers their score even further. All this affects their final grade and their employment prospects.”

Instructor, mathematics, engineering courses

Access to technology and resources: Institutional access to technology and resources affects the knowledge and skill of students, which in turn affects their employability. The location of the institute plays a crucial role as rural VET institutes face issues like irregular power supply and water cuts, which hamper the working of the institute and the training received by the students. The availability of machinery, materials and other resources were the other factors affecting employability mentioned in this context.

“My students need a lot of materials to master their trade like paint, canvas, brushes, etc. They must be provided to us in a timely manner or else students will just end up wasting their time. Also, they need to be able to explore their artistic abilities freely for them to be good at their trade. So the quantity of these materials also matters.”

Instructor, painter (general) course

Connections with the industry: The connection between the institute and the industry facilitates exposure to latest technology and workings of the industry through exposure visits. The connections of the industry and institute also affect graduates’ access to apprenticeships and jobs, thereby affecting their employability.

“Rural ITIs often do not have access to companies unless they are located near an industrial hub. Industrial visits and other kinds of industry exposure are also not available in that case. This affects their employability, especially when they are competing with graduates from urban institutes.”

Instructor, tool and die maker course

Reputation of the institute: Institutional attributes like the size and year of establishment were mentioned by respondents in the context of institutional reputation. The affiliation of the institute (private or government) was also found to affect the employability of the graduates. Established private training institutes and government institutes were regarded favorably by employers, but lesser known private institutes were not. This is supported by a study on ITIs conducted by Neroorkar and Gopinath (2019). This study showed that employers preferred workers trained at government institutes rather than those from lesser-known private institutes.

“Companies regularly visit larger institutes for apprenticeship selection and job fairs. Our institute is small and not known to most companies. Our students have to take an extra effort to approach companies or go to other institutes for job fairs. This affects their chances in the job market.”

Instructor, welding course

“Since our apprenticeship school is very old and well established, it has a good reputation in the industry. Graduates have high chances of employment once they complete their course from here.”

Ex-Deputy General Manager, Government Apprenticeship Training Institute

5 Implications and Conclusion

The framework put forth in this study provides a structure for conceptualizing and analyzing the components of the employability of Indian VET graduates. Based on this framework, the task of enhancing the employability of these graduates would involve

- training students in the necessary employability skills and attributes,

- training students to apply job search strategies effectively and helping them build a strong social network within their trade areas,

- ensuring that graduates are productive and maintain job-sustaining behaviour,

- provision of support to graduates in the form of child care facilities, transportation, and other facilities,

- remuneration of VET graduates as per standard norms,

- engagement of formally certified labor in the industry,

- open channels for recruitment of certified labor through online platforms accessible to all stakeholders,

- efficient regulation of private VET institutes,

- improvement of the quality of government and private institutes by setting high standards for infrastructure, resources, instruction, and practical training and

- establishing feedback mechanisms whereby the industry can communicate with the institutes regarding current practices.

VET has the potential to help India grow in an internationally competitive manner. However, with industrial modernization and the move away from traditional methods, the increasing demand on the VET sector cannot be met with the purely supply side planning approach adopted by VET program designers thus far (Pillay & Ninan 2014, 21). A holistic approach catering to both the supply and demand side by focusing on the individual, their circumstances, external factors and the institutions is essential. Additionally, the Indian VET system being very small and fragmented is in dire need of a “common conceptual platform” to help it progress and grow in a systematic manner (Mehrotra 2014b, 371). The present study provides a unifying conceptual structure that can be used to guide and direct the process of improvement of employability of Indian VET graduates through a coordinated effort between different entities like the central and state governments, institutes, and the industry.

References

Card, D., Chetty, R., & Weber, A. (2007). The spike at benefit exhaustion: Leaving the unemployment system or starting a new job? American Economic Review, 97(2), 113-118.

Comyn, P., & Barnaart, A. (2010). TVET reform in Chongqing: big steps on a long march. Research in Post‐Compulsory Education, 15(1), 49-65.

Crichton, S., & Childs, E. (2005). Clipping and coding audio files: A research method to enable participant voice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4(3), 40-49.

Directorate General of Training (DGT). 2019. Vocational Training. Online: http://dget.nic.in/content/vocational-training.php (retrieved 1.1.2019).

Evers, J. C. (2011). From the past into the future. How technological developments change our ways of data collection, transcription and analysis. In: Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 12, No. 1).

Fasick, F. A. (1977). Some uses of untranscribed tape recordings in survey research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 41(4), 549-552.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14-38.

Gravois, T., Rosenfield, S., & Greenberg, B. (1992). Establishing reliability for coding implementation concerns of school-based teams from audiotapes. Evaluation Review, 16, 562–569. doi:10.1177/ 0193841X9201600507

Halcomb, E. J., & Davidson, P. M. (2006). Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Applied Nursing Research, 19(1), 38-42.

Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: developing a framework for policy analysis. London: DfEE.

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2003). Industrial Training Institutes of India: The efficiency study report.

McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197-219.

Mehrotra, S. (2014a). From 5 million to 20 million a year: The challenge of scale, quality and relevance in India’s TVET. Prospects, 44(2), 267-277.

Mehrotra, S. (2014b). Quantity & quality: policies to meet the twin challenges of employability in Indian labor market. The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 367-377.

Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship. (2015). National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship. Online: https://www.msde.gov.in/assets/images/Skill%20India/policy%20booklet-%20Final.pdf (retrieved 8.1.2019).

Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/104973239500500201 (retrieved 18.10.2018).

Neal, J. W., Neal, Z. P., Van Dyke, E., & Kornbluh, M. (2015). Expediting the analysis of qualitative data in evaluation: A procedure for the rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA). American Journal of Evaluation, 36(1), 118-132.

Neroorkar, S. & Gopinath, P. (2019). The Impact of Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) on the employability of graduates – a study of government ITIs in Mumbai. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 72(1), 23- 46.

Pillay, H. K. & Ninan, A. (2014). India’s vocational education capacity to support the anticipated economic growth. BHP Billiton, Singapore. Online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/72103/1/72103_PILLAY_BHP_Report_Final_Report.pdf (retrieved 12.1.2019).

Prakash, B. S., & Gupta, K. P. (2002). Employability pattern of ITI graduates: a profile of the vocational education system. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 45(4), 1267.

Rajput, J. S. (2009). The changing context of TVET for the workforce in India. In International Handbook of Education for the Changing World of Work. Springer, Dordrecht, 2417-2430.

Rojewski, J. W. (2009). A conceptual framework for technical and vocational education and training. In: International handbook of education for the changing world of work. Springer, Dordrecht, 19-39.

Tammaro, A.M. (2005). Recognition and quality assurance in LIS: New approaches for lifelong learning in Europe. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 6 (2), 67-79.

Tessier, S. (2012). From field notes, to transcripts, to tape recordings: Evolution or combination? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(4), 446-460.

Tilak, J. B. (2003). Vocational education and training in Asia. In: International handbook of educational research in the Asia-Pacific Region. Springer, Dordrecht, 673-686.

Wahba, M. (2012). Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) challenges and priorities in developing countries. Online:

https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/TVET_Challenges_and_Priorities_in_Developing_Countries.pdf (retrieved 11.2.2018).

Appendix

List of questions used for interview/focus group discussion/questionnaire

| Component of employability | ITI Graduates | Instructors, Staff | Employers |

| 1. Gaining employment | How do you go about looking for jobs? How did you get your first job post ITI? What questions do you generally get asked in a job interview?Are employers interested in your other qualifications apart from the ITI certificate?Have you encountered any difficulties while securing a job? If yes, what were they? Have you ever been rejected? If yes, what could be the possible reason for that?According to you, what qualities in an ITI graduate, increase his/her chances of getting a job? | How do employers go about the recruitment process? How do students look for jobs in the industry? What do employers look for in an ITI graduate while recruiting?What kind of questions are graduates asked in a job interview? Are there any difficulties that students face while securing jobs? What are they? What are the possible reasons for rejection of ITI graduates at the recruitment stage?According to you, what qualities in an ITI graduate increase his/her chances of getting a job? | What are your sources for recruiting skilled workers? What do you look for in an ITI graduate who is a prospective employee? What kind of questions do you ask ITI graduates during the recruitment process?Do you look at the applicant’s other qualifications apart from the ITI certification? What are your preferences while recruiting ITI graduates with respect to (a) experience (b) affiliation of the institute – private or government? Any other preferences? What are your reasons for these preferences?What are your reasons, if any, for rejecting ITI graduates? |

| 2. Maintaining employment | What do employers expect from you while on the job?On what basis do salary increments and promotions take place in your company/industry? Have you ever seen/heard of ITI graduates being fired? What could possibly be the reason for that?What are your expectations from your job?Do you face any problems in your workplace? If yes, what are they?Who is a successful ITI graduate in your opinion? | What do employers expect from ITI graduates while on the job?On what basis do salary increments and promotions take place in the industry? Have you heard of ITI graduates being fired? What could be the possible reason for that? What are the kind of expectations that ITI graduates have from their job?Have your ex-students ever shared any workplace related problems with you? If yes what were they?Amongst all the students you have taught at the ITIs, can you remember an exemplary student/students? What makes him/her/them better than the rest? Who is a successful ITI graduate in your opinion? | Is there a training period for skilled workers in your company? If yes what is the duration?What is the nature of the training given?What are your expectations from ITI graduates while on the job? What is the basis for salary increments and promotion of ITI graduates in your organization? Have you ever fired ITI graduates? What were the reasons? What, according to you, do ITI graduates expect from their job?What are the kind of problems (if any) that ITI graduates encounter while on the job?Can you remember an excellent ITI worker in your organization? What qualities made him/her better than the rest? |

| 3. Securing new employment | Have you ever changed jobs?What were the reasons for the change? | What are the reasons for switching of jobs by students? |

Citation:

Neroorkar, S. & Gopinath, P. (2020). An Employability Framework for Vocational Education and Training Graduates in India: Insights from government VET institutes in Mumbai In: TVET@Asia, issue 15, 1-18. Online: https://tvet-online.asia/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/03_Neroorkar-and-Gopinath_2020-07-20_Vorlage-Final.pdf (retrieved 30.06.2020).